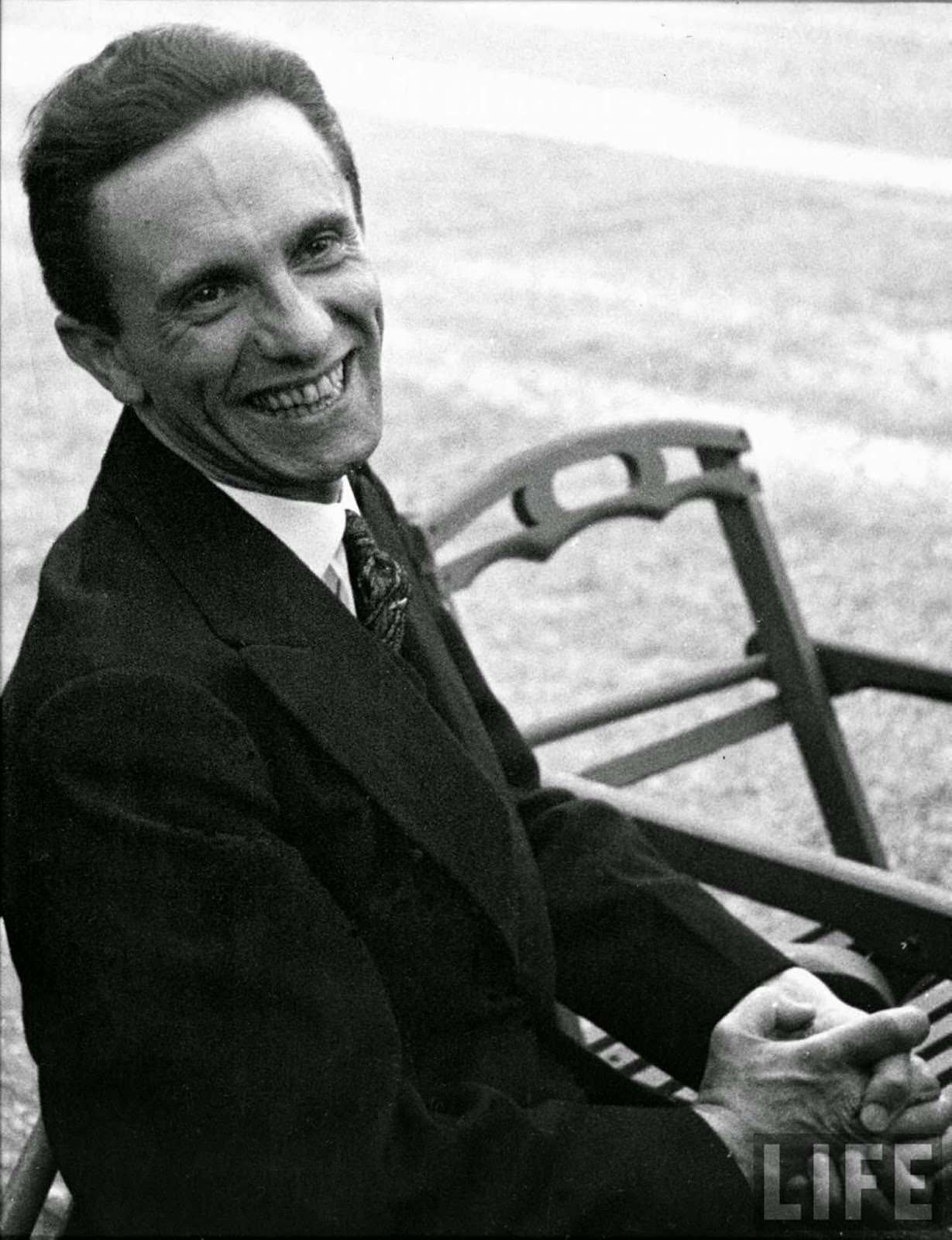

It is a look that stops you cold. Honestly, if you’ve spent any time looking at historical photography, you’ve likely stumbled across the eyes of hate photo, though you might not have known the exact context immediately. The image features Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda. He’s sitting in a chair in a garden in Geneva. His hands are gripped onto the armrests. His posture is rigid. But it’s the eyes—those dark, narrow slits of pure, unadulterated venom—that stay with you.

Photography has this weird way of capturing a soul when it isn't ready to be seen. Usually, Goebbels was a man who obsessed over his image. He knew his angles. He knew how to look like a statesman or a visionary. But in this specific moment, captured by Alfred Eisenstaedt in 1933, the mask didn't just slip. It was ripped off.

The Moment Everything Changed for Alfred Eisenstaedt

The year was 1933. The League of Nations was meeting in Geneva. This was a fragile time for the world. Hitler had recently come to power, and the international community was watching with a mix of curiosity and growing dread. Alfred Eisenstaedt, a Jewish photographer born in West Prussia (modern-day Poland), was there on assignment for Life magazine.

Eisenstaedt was already a legend in the making. He had this incredible ability to be a "fly on the wall." Earlier in the day, he had actually photographed Goebbels, and the results were totally different. In those earlier shots, Goebbels is smiling. He looks almost charming, or at least as charming as a man like that can look. He was playing the part of the diplomat.

Then, something happened.

Goebbels found out that Eisenstaedt was Jewish.

The shift was instantaneous. In an interview years later, Eisenstaedt recalled that Goebbels looked at him with "hateful eyes" and waited for him to wither. He didn't. Instead, he lifted his Leica and clicked the shutter. That single frame became the eyes of hate photo, a definitive visual representation of the third reich's core ideology: pure, irrational prejudice.

Why the Eyes of Hate Photo Still Hits Hard in 2026

We live in an era of high-definition video and constant surveillance. Yet, a grainy black-and-white photo from nearly a century ago still carries more weight than most modern political "gotcha" moments. Why? Because it’s one of the few times in history where evil forgot to blink.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

Most of the time, historical villains are presented to us in two ways: as cartoonish monsters or as sterile figures in a textbook. This photo does neither. It shows a small man. Goebbels was famously short, standing about 5'5", with a clubfoot that he was deeply insecure about. In the eyes of hate photo, you see all that insecurity curdling into malice. It’s the look of a man who feels superior because he has decided the person in front of him is subhuman.

It’s chilling.

You can almost feel the temperature in the garden drop. Eisenstaedt later said, "He looked at me with hateful eyes and waited for me to wither. But I didn't wither." That’s an important distinction. The power in the photo isn’t just in Goebbels' expression; it’s in the bravery of the man behind the lens who refused to look away.

Breaking Down the Visual Composition

If you look at the framing, it’s actually quite intimate. Eisenstaedt used a 35mm Leica, a camera that allowed him to be mobile and candid.

- The Grip: Look at his hands. They aren't relaxed. They are claw-like.

- The Lean: He’s leaning forward slightly, as if he’s about to lunge.

- The Shadow: The lighting in Geneva that day was bright, but the shadows under his brow make his eyes look like empty sockets.

It’s a masterclass in spontaneous portraiture.

The Context of 1933: A World on the Edge

To really get why the eyes of hate photo matters, you have to remember what was happening in 1933. This wasn't 1945. The world didn't fully know what was coming. Concentration camps were in their infancy. The Holocaust hadn't begun in earnest.

Goebbels was in Geneva to play nice with the League of Nations. He was trying to convince the world that Germany just wanted "equality" among nations. The photo exposes the lie. It shows that beneath the suits and the diplomatic talk, there was a foundation of raw, visceral hatred for the "other."

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

Eisenstaedt’s Jewishness wasn't just a personal detail; it was the catalyst for the image. The moment Goebbels realized he was being documented by a man he considered "untermensch," his diplomatic veneer shattered. It’s a rare moment of historical honesty.

Misconceptions About the Photograph

People often get a few things wrong about this image.

Some think it was a staged propaganda photo that went wrong. It wasn't. Goebbels hated it. He lived for control, and this was a moment where he had none.

Others think Eisenstaedt was in immediate physical danger. While the atmosphere was undoubtedly tense, this was Geneva, not Berlin. Goebbels couldn't simply have him arrested on the spot. However, the psychological pressure must have been immense. Imagine standing feet away from one of the most powerful and dangerous men in the world, knowing he despises your very existence, and choosing to take his picture anyway.

That’s some serious backbone.

The Legacy of Alfred Eisenstaedt

Eisenstaedt eventually fled Germany in 1935. He came to the United States and became one of the most famous photographers in history. You probably know his other "big" shot: the sailor kissing the nurse in Times Square on V-J Day.

It’s wild to think that the same man took both photos. One represents the ecstasy of peace; the other represents the root cause of the war.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

The eyes of hate photo serves as a warning. It’s a reminder that prejudice isn't always a grand, sweeping speech. Sometimes, it’s just a look. It’s a silent, cold rejection of someone’s humanity.

Analyzing the Impact on Modern Media

In a world of "fake news" and AI-generated imagery, the authenticity of the eyes of hate photo is its greatest strength. You can’t fake that level of tension.

Historians often use this photo to teach the concept of the "banality of evil," though Goebbels was anything but banal. He was a calculated architect of misery. But in this photo, he just looks like a bitter, angry man. It strips away the "Great Orator" myth that the Nazis worked so hard to build.

When you look at this photo, you aren't looking at a powerful minister. You’re looking at a bully who just realized he’s being watched by someone he can't scare.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student of history, a photography enthusiast, or just someone interested in human psychology, there are a few ways to engage with this piece of history more deeply:

- Study the rest of the Geneva series: Look for the "smiling" photos of Goebbels from that same day. The contrast is where the real story lives.

- Read Eisenstaedt’s autobiography: He goes into detail about the technical challenges of using a Leica in the early 30s.

- Visit the Archives: Life magazine’s archives (now often hosted via Google Arts & Culture) have high-resolution versions that allow you to see the grain and the detail in Goebbels' expression.

The eyes of hate photo isn't just a picture of a Nazi. It’s a document of a moment where the truth became unavoidable. It’s a testament to the power of the camera to act as a mirror to the soul, whether the subject likes what’s being reflected or not.

Next time you’re scrolling through historical archives, find the high-res version. Look closely at the eyes. It’s a chilling experience, but a necessary one if we want to understand how the 20th century really felt.

To explore more about historical photography, look into the work of Margaret Bourke-White or Robert Capa, who also captured the raw, unvarnished reality of the era. Understanding the equipment used—like the Leica III—can also provide a deeper appreciation for how these "candid" moments were even possible in an era of bulky, slow cameras.