Imagine walking into a Sears in 1950. You’ve got fifty bucks in your pocket—a small fortune back then—and you want to buy your kid something special. You bypass the train sets. You ignore the lead soldiers. Instead, you reach for a bright red box that promises to teach your child the secrets of the universe.

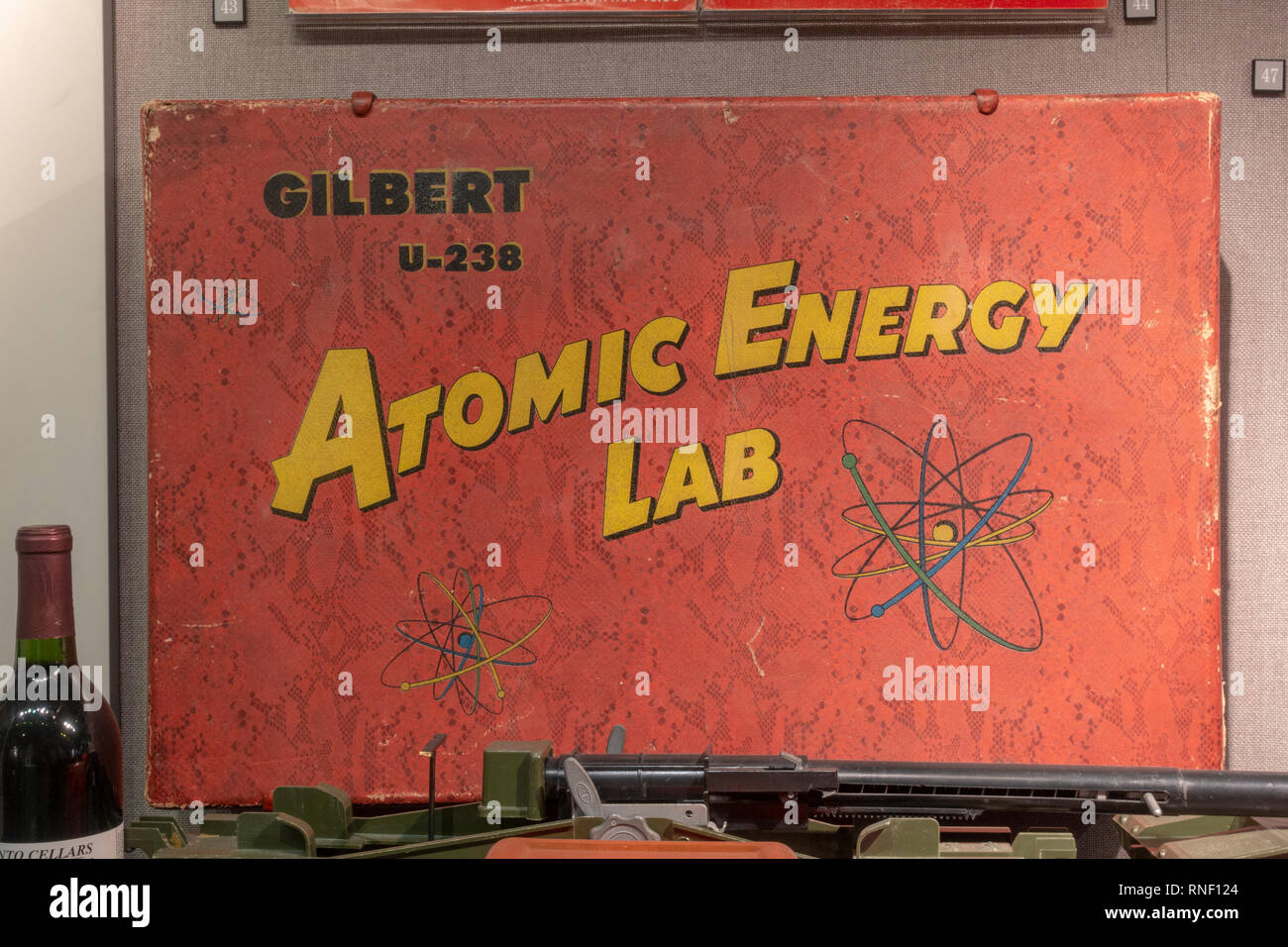

It was called the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab.

Inside that box? Actual radioactive isotopes. We aren’t talking about glow-in-the-dark stickers or plastic replicas. We are talking about four types of uranium ore and three distinct radiation sources. To a modern parent, this sounds like a plot point from an HBO miniseries about a nuclear meltdown. To Alfred Carlton Gilbert, the man behind the Erector Set, it was just the "most spectacular" educational tool ever devised. He wasn't trying to be a mad scientist. He honestly believed that the "Atomic Age" required a generation of kids who weren't afraid of the Geiger counter.

What was actually inside the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab?

People love to exaggerate for the sake of a good story. You’ll hear folks claim this toy could level a city block or that it gave every kid in the fifties a third arm. That’s nonsense. However, the reality of the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab is still wild enough that it doesn't need the hyperbole.

The kit was a miniature laboratory. It came with a cloud chamber where you could literally watch alpha particles zipping through vapor. It had a spinthariscope for seeing radioactive decay in real-time. There was an electroscope to measure ionization. But the stars of the show were the samples. You got Alpha, Beta, and Gamma sources: specifically Pb-210 (Lead), Ru-106 (Ruthenium), and Zn-65 (Zinc). Then there were the jars of uranium-bearing ore collected from the Colorado Plateau.

It was thorough.

Gilbert even included a 60-page instruction book and a comic book titled Learn How Dagwood Splits the Atom. The government was actually involved in this. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) worked closely with Gilbert because they wanted the public to view nuclear power as something helpful and manageable, not just a precursor to a mushroom cloud.

💡 You might also like: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Why did it fail so spectacularly?

It wasn't the radiation that killed the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab. It was the price tag.

$49.50.

In 1950, that was roughly equivalent to spending $600 on a toy today. Most families couldn't justify that kind of cash for a chemistry set, no matter how "educational" it claimed to be. It stayed on the shelves for only about a year, from 1950 to 1951. Gilbert only sold about 5,000 units. Because they sold so poorly, they became instant collector's items. If you find a complete one in a basement today, you're looking at a five-figure payday at an auction.

The other problem was complexity. This wasn't a "set it and forget it" toy. You had to understand some pretty dense physics to even get the cloud chamber working correctly. Most kids probably just looked at the rocks, played with the Geiger counter for ten minutes, and went back to playing stickball.

The safety myth vs. the radioactive reality

We live in a world of rounded corners and warning labels on coffee cups. From that perspective, putting Po-210 in a child's hands is insanity. But let’s look at the nuance.

The radiation levels in the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab were relatively low. If you kept the samples in their containers, the exposure was roughly equivalent to a day of natural background radiation or a few hours in the sun. The "danger" was largely theoretical, provided the kid didn't decide to eat the rocks.

📖 Related: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

"The radiation was about the same as you'd get from the sun's UV rays," Gilbert once defended.

He wasn't entirely wrong, but he was downplaying the "ingestion" factor. If a curious eight-year-old swallowed one of those alpha-emitting sources, the internal damage would be a very different story. Alpha particles are stopped by a sheet of paper—or your skin—but once they are inside your soft tissues, they act like tiny, microscopic wrecking balls.

What the kit actually taught kids

If you were one of the lucky few to own one, you weren't just playing. You were conducting high-level experiments. The kit encouraged kids to:

- Use the Geiger-Mueller Counter to go "prospecting" around their neighborhood for uranium.

- Observe the "tracks" of particles in the cloud chamber.

- Understand the difference between various types of radioactive decay.

It was a peak example of "learning by doing." There were no screens. No simulations. It was raw physics in a wooden box.

The legacy of A.C. Gilbert’s "Most Dangerous" invention

A.C. Gilbert was a fascinating guy. He was an Olympic gold medalist in pole vaulting. He was a physician. He was a magician. He basically invented the concept of the educational toy. He believed that American boys—and back then, the marketing was very much aimed at boys—needed to be "men of tomorrow."

The Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab was the pinnacle of that philosophy.

👉 See also: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Today, the toy is a staple in museums like the Smithsonian and the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History. It represents a brief, bizarre window in history where the world was so enamored with the potential of the atom that we forgot to be afraid of it. It was the "Atomic Age" in a microcosm.

Honestly, we will never see anything like it again. Modern safety regulations, specifically the Federal Hazardous Substances Act, would laugh this thing out of a boardroom before the pitch even started. But there is something sort of beautiful about the ambition of it. It treated children like capable, intelligent explorers of the natural world rather than fragile consumers.

Practical takeaways for the modern collector or enthusiast

If you are obsessed with the history of the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab, or if you’re actually looking to track one down, here is the reality of the situation:

1. Check the Geiger counter first.

Most surviving kits have broken Geiger counters. The vacuum tubes are fragile and the batteries they used are long out of production. If you’re buying one as an investment, the "completeness" of the paper ephemera (the manuals and the Dagwood comic) often matters more than the functionality of the hardware.

2. Storage matters.

If you own a kit, don't keep it on your nightstand. While the radiation is low, it’s still an active source of radon gas as the isotopes decay. Keep it in a well-ventilated area or a sealed display case in a room you don't spend 8 hours a day in.

3. Authenticate the ore.

Because these kits are so valuable, people "frankenstein" them. They’ll take a wooden box from a different Gilbert set and toss in some random rocks. Genuine U-238 lab ore jars have specific labels and the ore itself has a distinct look based on where it was sourced in the 1950s.

4. Respect the physics.

Even 75 years later, those sources are still "hot." They haven't reached their half-life limits to the point of being inert. Treat the kit with the respect a laboratory instrument deserves, not as a gag gift.

The Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Lab remains a testament to a time when science was synonymous with progress, and progress was worth a little bit of risk. It’s a piece of history that glows—both metaphorically and, if you’ve got a good enough sensor, literally.