It was the only part of the Space Shuttle stack that didn't come home. When you look at those old photos of Discovery or Atlantis sitting on the pad, your eyes usually go to the white orbiter with its wings or the thin, powerful solid rocket boosters on the sides. But the massive, rust-colored pillar in the middle—the external fuel tank space shuttle component—was basically the backbone of the entire mission. Without it, the shuttle was just a very expensive glider sitting in Florida.

Think about the sheer scale for a second. We’re talking about a structure over 150 feet tall. It held more than 1.6 million pounds of propellant. Honestly, calling it a "tank" feels like calling the Great Pyramids "some rocks." It was a masterpiece of aerospace engineering that had to be strong enough to support the weight of the orbiter while being light enough to not drag the whole mission down.

The Color of Insulation

If you’re old enough to remember the very first shuttle launches, STS-1 and STS-2, you might remember the tank was white. NASA painted the first two external fuel tanks to protect the insulation from ultraviolet light. But they quickly realized they were wasting weight.

Painting that massive surface area added about 600 pounds to the stack. In the world of spaceflight, 600 pounds is a massive penalty. By ditching the paint and letting the spray-on foam insulation (SOFI) turn its natural orange-brown through sun exposure, NASA could carry more cargo into orbit. It was a practical, "ugly" choice that saved millions of dollars over the life of the program.

The foam itself was a specialized polyurethane-polyisocyanurate material. It had a tough job. Inside the tank, you had liquid hydrogen at $-423^{\circ}F$ and liquid oxygen at $-297^{\circ}F$. Outside, the Florida humidity was trying to turn that tank into a giant popsicle. The foam prevented ice from forming, which was critical because falling ice could—and did—damage the orbiter's fragile heat tiles.

Structural Anatomy and the "Intertank"

The tank wasn't just one big hollow tube. It was actually three separate structures bolted together. At the very top was the liquid oxygen tank. It was an ogive shape to reduce drag. Below that was the "intertank." This was the unpressurized bridge that connected the oxygen and hydrogen sections.

The intertank was the real workhorse. It housed the electronics and served as the primary attachment point for the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). When those SRBs ignited, they provided millions of pounds of thrust. All that force was transmitted through the intertank. If that section failed, the whole vehicle would have buckled like a soda can under a boot.

✨ Don't miss: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Then you had the massive liquid hydrogen tank at the bottom. It was two and a half times larger than the oxygen tank but held much less mass because liquid hydrogen is incredibly light. Everything was made of aluminum-lithium alloy (Al-Li 2195). NASA switched to this lighter alloy later in the program to squeeze even more performance out of the external fuel tank space shuttle design.

The Tragedy of Foam Shedding

We have to talk about the dark side of this technology. For years, engineers knew that bits of foam would occasionally flake off during ascent. They called it "popcorn." Most of the time, it was harmless.

That changed with STS-107. On the launch of Columbia in 2003, a piece of foam about the size of a briefcase broke off the "bipod ramp"—the area where the tank connects to the orbiter's nose. It struck the leading edge of the left wing. Because the shuttle was traveling at thousands of miles per hour, that foam hit with the force of a cannonball.

It punched a hole in the Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC) panels. During reentry, superheated plasma entered the wing and destroyed the spacecraft. This tragedy forced NASA to completely redesign how the foam was applied. They eventually removed the foam ramps entirely and replaced them with electric heaters to prevent ice buildup. It was a somber reminder that in spaceflight, even a "passive" component like a fuel tank can be a single point of failure.

Disposal: The 400-Mile Long Dive

Unlike the SRBs, which parachuted into the ocean to be fished out and reused, the external fuel tank was disposable. It was the only part of the shuttle stack that was "expendable."

Once the shuttle reached near-orbital velocity—about 8.5 minutes after liftoff—the main engines would shut down (a process called MECO). A few seconds later, the orbiter would fire explosive bolts, and the tank would drift away.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

But it didn't just float off into deep space.

NASA specifically designed the trajectory so the tank would fall back toward Earth. It would tumble and break apart over the Indian Ocean or the Pacific, far away from shipping lanes. Most of it vaporized during reentry. The pieces that survived the heat hit the water at terminal velocity. Basically, every single mission ended with a multi-million dollar piece of hardware being intentionally destroyed.

Could We Have Saved Them?

There was a group of engineers and enthusiasts who hated seeing those tanks go to waste. They proposed the "External Tank Station" concept. The idea was simple: instead of dropping the tank, the shuttle would carry it all the way into orbit.

Once in space, you’d have a massive, pressurized volume already up there. You could have turned them into space stations, fuel depots, or even giant telescopes. One plan suggested that since the tanks were already "flight proven," you could link several together to create a massive rotating habitat.

Ultimately, NASA passed. The cost of carrying the extra weight of the tank all the way to orbital velocity was too high. Plus, outfitting a used fuel tank in a vacuum is way harder than it sounds. You’d have to scrub out the residual chemicals and find a way to make it habitable. It’s one of those "what if" scenarios that still haunts space nerds today.

Technical Specifications and Variations

NASA didn't just build one type of tank. They iterated.

💡 You might also like: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

- Standard Weight Tank (SWT): The original. Used for the early missions. Heavy but reliable.

- Lightweight Tank (LWT): Introduced in the early 80s. They thinned out some of the structural ribs and saved about 6,000 pounds.

- Super Lightweight Tank (SLWT): The final evolution. Made from that aluminum-lithium alloy mentioned earlier. It was about 7,500 pounds lighter than the LWT. This version was crucial for the International Space Station (ISS) missions because it allowed the shuttle to carry the heavy station modules into a high-inclination orbit.

Feeding the engines was a feat of plumbing. The "umbilicals" at the bottom of the tank were huge. The liquid oxygen flowed through a 17-inch diameter pipe that ran down the outside of the tank. If you look at photos, you can see this "feedline" running along the side. It delivered the propellant at a rate that would drain a backyard swimming pool in seconds.

Why the Design Still Influences Us

The Space Shuttle is retired, but the legacy of the tank lives on. If you look at NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), that big orange core stage looks awfully familiar. That’s because it’s basically a stretched version of the external fuel tank space shuttle design.

The SLS uses the same insulation, the same manufacturing techniques at the Michoud Assembly Facility in Louisiana, and even the same diameter. It’s a testament to how good the original engineering was. They took a 1970s design and found it was still the most efficient way to hold cryogenic fuel for a massive rocket in the 2020s.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the history or even see one of these behemoths in person, there are a few things you can actually do:

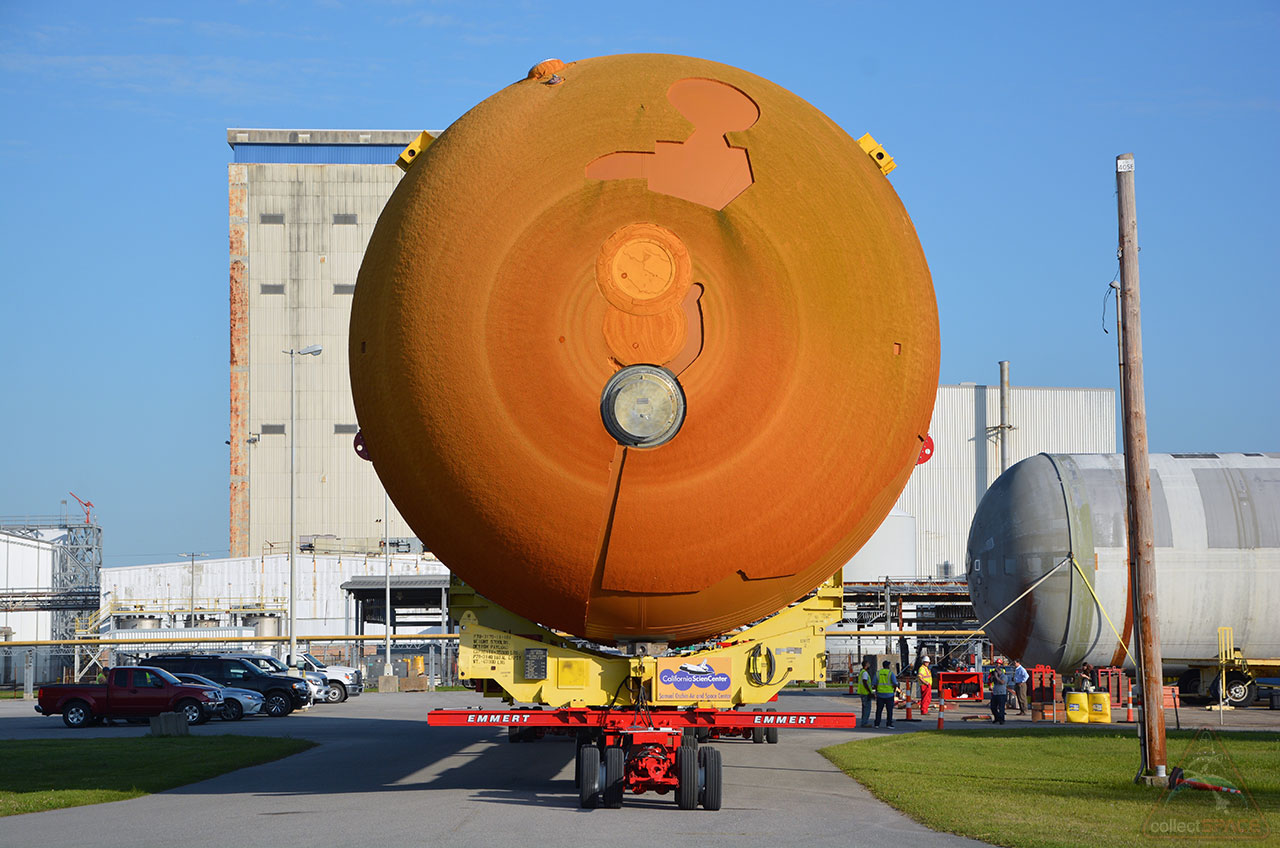

- Visit the Remaining Tank: There is only one flight-qualified external tank left on Earth that didn't fly. ET-94 is currently on display at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. It’s being displayed in a full "vertical" stack with the orbiter Endeavour. Seeing it in person is the only way to truly grasp the scale.

- Study the Michoud Facility: The Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans is where these tanks were built. You can find archival footage of the "friction stir welding" process they used. It’s a fascinating look at how you join massive sheets of aluminum without traditional melting.

- Analyze the "Shedding" Reports: If you are into the technical side of safety, the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) report is public. It’s a dense read, but chapters 3 and 4 go into incredible detail about the physics of the foam and the aerodynamics of the tank during the first few minutes of flight.

- Check the SLS Core Stage Progress: Since the SLS core stage is the direct descendant, following its "Green Run" tests provides a modern context for how liquid hydrogen and oxygen tanks are managed today. The sensors and "pogo" suppression systems are remarkably similar to the shuttle era.

The external tank was never the star of the show. It didn't have the "cool" factor of the wings or the roar of the engines. But it was the lifeblood of the program. It was a massive, fragile, indispensable container that held the energy required to leave the planet. Next time you see a shuttle launch video, don't just watch the shuttle. Look at the orange giant holding it all together.

Next Steps for Research

Look into the "Space Tug" concepts from the 1970s which originally envisioned the external tank as a long-term orbital asset. You might also want to search for the specific chemical composition of the BX-250 and BX-265 foams to understand the environmental challenges NASA faced when they had to remove CFCs from the production process in the 1990s.