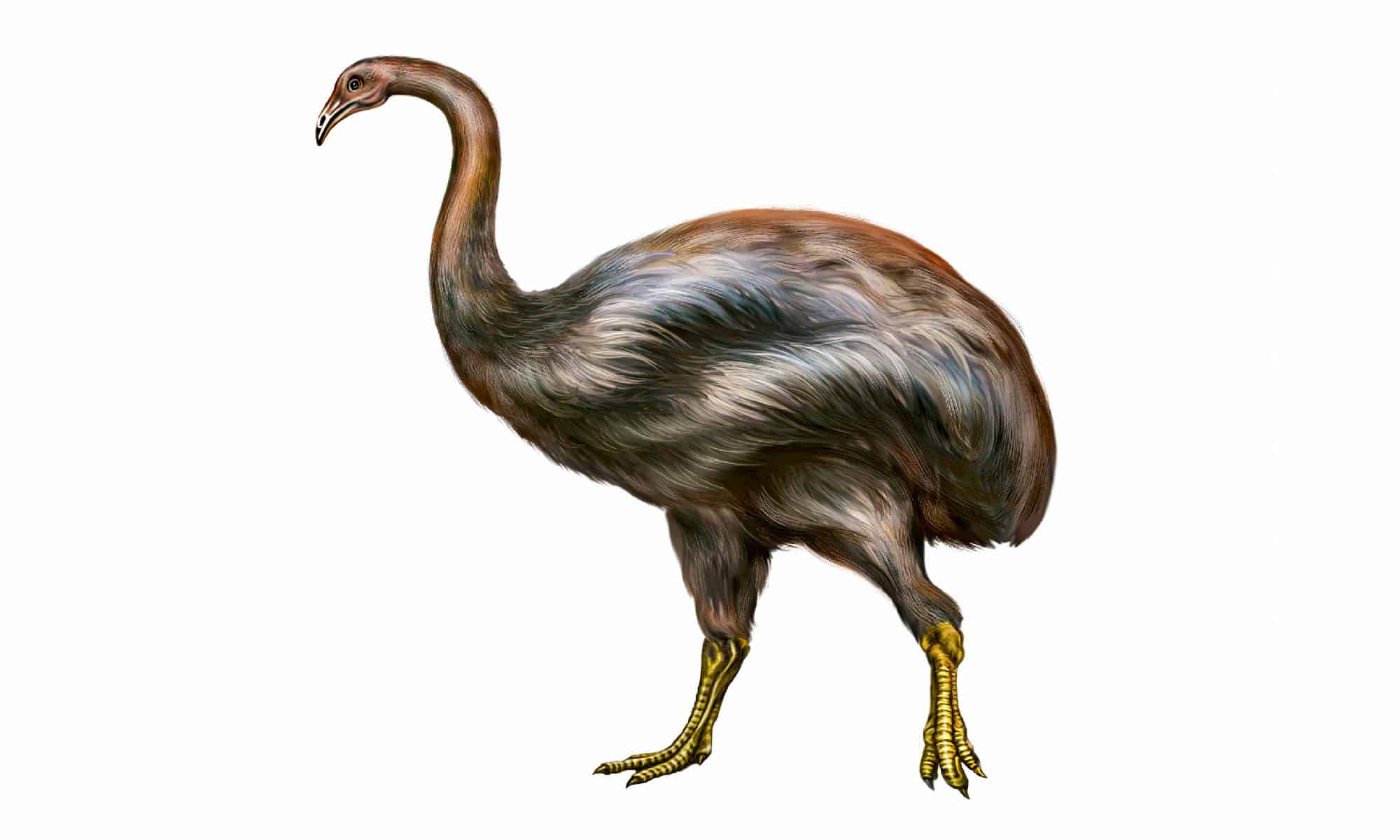

Imagine walking through a dense, foggy podocarp forest on New Zealand’s South Island about six hundred years ago. You aren’t the top of the food chain. Not even close. You hear a thud. Then another. It’s not a mammal. New Zealand didn’t really do mammals back then, aside from a couple of bats. No, the sound comes from something with feathers, a neck like a prehistoric snake, and legs thicker than a modern rugby player’s thighs. This was the Giant Moa, a bird that defied everything we think we know about avian evolution.

Honestly, it’s hard to wrap your head around just how weird these things were.

They weren't just "big birds." They were biological anomalies. While ostriches and emus have tiny, useless wings, the moa took things a step further. They had no wings at all. Zero. Not even vestigial little stumps. Evolution looked at the moa and decided that wings were a total waste of energy in a land with no land-based predators. For millions of years, it worked. Until it didn't.

The Reality of the Giant Moa and Why They Vanished

When people talk about the Giant Moa (Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezealandiae), they usually picture a giraffe-like bird standing bolt upright. You've probably seen those old museum sketches. Tall. Majestic. Head poking into the canopy.

Well, the science has shifted.

Biomechanical analysis suggests that if a moa held its neck vertically for too long, it would have probably put a ridiculous amount of strain on its vertebrae. They likely walked with their heads held forward, more like a grazing animal than a flagpole. It’s a bit less "majestic" and a bit more "terrifying forest vacuum."

✨ Don't miss: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

These birds were massive. A large female Dinornis robustus could reach heights of about 3.6 meters (12 feet) and weigh somewhere in the neighborhood of 230 kilograms. That is a lot of bird. Interestingly, the males were tiny by comparison. It’s one of the most extreme cases of sexual dimorphism in the animal kingdom; the females were sometimes twice as tall and three times as heavy as their mates. Imagine a world where the "average" couple looks like a housecat paired with a tiger.

The Haast’s Eagle Factor

You can't talk about the moa without talking about the thing that ate them. Because New Zealand lacked lions or wolves, the "apex" spot was filled by the Haast’s Eagle (Hieraaetus moorei). This wasn't a scavenger. It was a three-meter-wingspan nightmare that dropped from the sky like a feathered anvil.

It hunted the Giant Moa.

Think about that for a second. An eagle powerful enough to knock down a 200kg bird. The eagle would strike the moa’s pelvis or head with talons the size of tiger claws. It’s one of the most intense predator-prey relationships in history, and it vanished almost overnight. When humans arrived—the Māori—around the late 13th century, they found a "naive" population of giants. The moa had never seen a human. They didn't run. They were easy pickings.

Within about 100 to 150 years, they were gone. All of them. Nine species, ranging from the turkey-sized coastal moa to the giants, wiped out. And because their only predator, the Haast’s Eagle, relied on them for food, the eagle went extinct right alongside them. It’s a textbook ecological collapse.

🔗 Read more: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

Where the Science Stands Today

We actually know a lot about them because of where they died. New Zealand is full of limestone caves and peat bogs. These places are essentially nature's Tupperware. We have found fully preserved feet with skin and muscle still attached. We have feathers. We have mummified heads.

Dr. Trevor Worthy, a name you’ll see on almost every major moa study, has spent decades piecing together their DNA and bone structure. Through mitochondrial DNA sequencing, we’ve learned that their closest living relatives aren't the Kiwi—which is what everyone assumes because they both live in NZ—but the Tinamous of South America. This implies that the moa's ancestors flew to New Zealand after it broke away from Gondwana, then gave up flight once they realized life was pretty chill on the ground.

- The Diet: We know exactly what they ate because we’ve found "coprolites" (fossilized poop). They loved twigs, berries, and leaves. They were the primary "gardeners" of the New Zealand bush.

- The Eggs: Moa eggs were huge. Some were about 24 centimeters long. Imagine trying to make an omelet with that; you’d need a frying pan the size of a manhole cover.

- The Sounds: While we can't be 100% sure, their trachea structure suggests they made low-frequency booming sounds. Deep, resonant calls that could travel for miles through thick forest.

Why We Should Care About a Dead Bird

You might think, "Okay, it's a big extinct bird. So what?"

But the Giant Moa is a warning. It's the most dramatic example of how quickly an ecosystem can be dismantled. New Zealand's entire flora evolved around the moa. Many native plants have "divaricating" branches—tight, tangled messes of twigs—that scientists believe evolved specifically to make it harder for moa to pluck off leaves. The plants are still armored for a war against a ghost.

The loss of the moa changed the very shape of the forest. Without these massive herbivores to clear the underbrush and spread large seeds, the forest grew denser and changed its composition.

💡 You might also like: 10 day forecast myrtle beach south carolina: Why Winter Beach Trips Hit Different

There's also the "de-extinction" debate. Because we have such high-quality DNA, the moa is often cited as a candidate for cloning. But there's a catch. Where would they go? The New Zealand of 2026 isn't the New Zealand of 1300. We have fences, highways, and dairy farms. A 12-foot bird wandering onto a state highway isn't just a biological miracle; it's a traffic hazard.

A Few Surprising Facts

- Māori oral traditions (moteatea and whakataukī) contain references to the moa, though by the time Europeans arrived, the birds were already legendary figures of the past.

- Some early explorers thought they might still be alive in the rugged Fiordland wilderness. They weren't.

- They had a very slow reproductive rate. This is ultimately what killed them; they couldn't out-breed the rate at which they were being hunted.

If you ever get the chance to visit the Te Papa Museum in Wellington or the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, stand next to a reconstructed skeleton. It’s humbling. You realize that humans are just a blip in the timeline of these islands. The moa ruled for millions of years. We’ve been here for less than a thousand.

To really understand the Giant Moa, you have to stop looking at them as "failed" evolution. They were perfectly adapted for a world that no longer exists. They were the masters of their domain until the rules of the game changed too fast for them to keep up.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to dive deeper into the world of the moa, don't just stick to Wikipedia. Look for the work of Sir Richard Owen, who first identified the moa from a single bone fragment in 1839. It's one of the greatest "Sherlock Holmes" moments in biology.

For those in New Zealand, head to Waitomo or the Caves of the South Island. Many of these sites still contain "moa pits"—natural traps where these birds fell and were preserved for centuries. Seeing a bone in the ground where it actually lay for 600 years hits different than seeing it behind glass.

Finally, support local conservation efforts like Zealandia or the Department of Conservation (DOC). While the moa is gone, their smaller "cousins" like the Takahe and the Kiwi are still hanging on. Protecting the habitat that remains is the only way to ensure we don't end up writing articles like this about the birds we still have.