You know that feeling when you're watching a movie and you keep thinking, "There is no way this actually happened"? That’s basically the entire experience of watching The Ghost and the Darkness. It’s a 1996 flick starring a peak-era Val Kilmer, and honestly, it’s one of the most intense "man vs. nature" stories ever put on film.

But here is the kicker: the Val Kilmer movie about lions is actually based on a true story that is arguably scarier than the Hollywood version.

In 1898, the British were trying to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in what is now Kenya. They were behind schedule, over budget, and generally struggling. Then, two lions showed up. They didn't just hunt for food; they seemingly hunted for sport, terrorizing thousands of workers for nine months. Val Kilmer plays Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson, the real-life engineer sent to finish the bridge and, eventually, kill the "demons" stopping the British Empire in its tracks.

The Reality of the Tsavo Man-Eaters

If you’ve seen the movie, you remember the lions as these massive, maned beasts that looked like they walked off a cereal box. In reality, the Tsavo lions were maneless.

Scientists have debated for a century why they didn't have manes. Some say it was the heat; others think the thick thorn bushes would have ripped a big mane to shreds. Whatever the reason, it made them look distinct—and to the workers, maybe a bit more supernatural.

The film claims these lions killed over 130 people. That number comes directly from Patterson’s own book, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo. However, modern isotopic analysis of the lions' remains (which are actually on display at the Field Museum in Chicago) suggests the number was likely closer to 28 or 35.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

Is 35 deaths less scary than 135? Not really. Especially when you consider they were dragging men out of "impenetrable" thorn enclosures called bomas.

Why did they do it?

Most lions don't hunt humans. We’re bony, we’re weird, and we fight back. But these two were different. Researchers found that both lions had severe dental issues. One had a root abscess that probably made hunting buffalo or zebras incredibly painful. Humans, by comparison, are soft. We don't have thick hides or horns. We were easy prey.

There’s also a darker historical context. The Tsavo region was a route for slave caravans. Sick or dying slaves were often left behind, providing a "steady supply" of human remains that may have given the local lion population a taste for us long before the railroad workers arrived.

Val Kilmer, Michael Douglas, and the "Remington" Myth

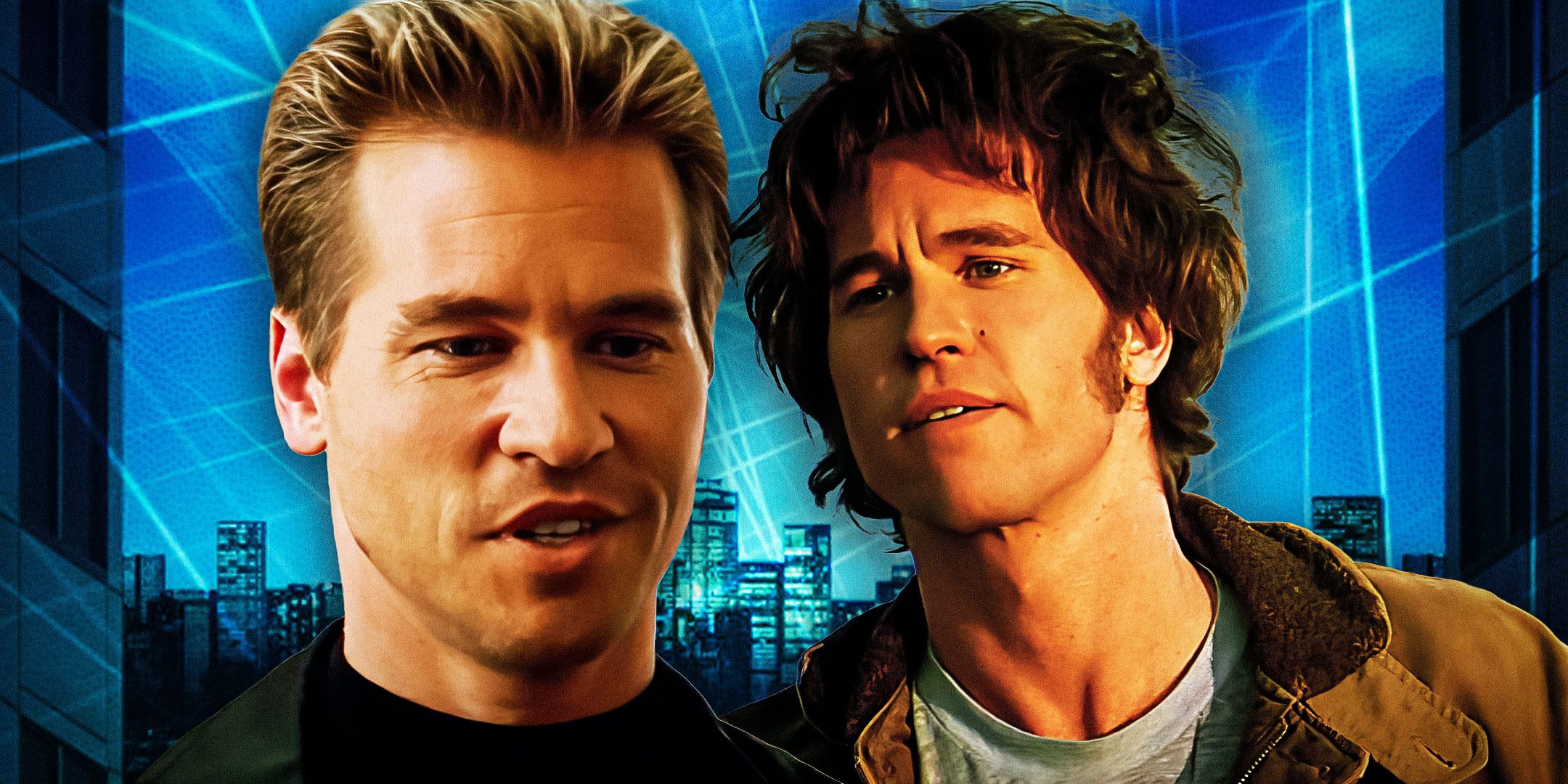

Val Kilmer was coming off Batman Forever and Heat when he took this role. He plays Patterson as a focused, slightly arrogant engineer who quickly realizes he’s in over his head. His performance is solid, but the movie really shifts gears when Michael Douglas shows up.

Douglas plays Charles Remington, a legendary Great Plains hunter.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Here is a fun fact: Remington didn't exist. The screenwriter, the legendary William Goldman (who wrote The Princess Bride and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid), felt that Patterson needed a foil. In the real story, Patterson hunted the lions mostly on his own or with local trackers. But for a $55 million Hollywood production, you apparently needed a second big star to come in and look cool with a double-barrel rifle.

Douglas was actually a producer on the film first. He initially offered the role of Remington to Sean Connery and Anthony Hopkins. When they both passed, he decided to play the part himself, which led to the character being expanded.

The Hospital Massacre: Fact vs. Fiction

One of the most terrifying scenes in the movie involves a brutal attack on the workers' hospital. In the film, it’s a bloodbath.

In real life, something very similar happened. Patterson had moved the hospital to a new location, thinking it would be safer. He left a "trap" at the old hospital site—a railcar with cattle and a couple of hunters waiting. The lions ignored the trap entirely and attacked the new hospital.

They were smart. They were patient. And they seemed to know exactly what Patterson was planning. This is why the workers started calling them "The Ghost" and "The Darkness." They weren't just animals; they were perceived as spirits or devils.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Why the Movie Still Holds Up

The Ghost and the Darkness won an Oscar for Best Sound Editing, and you can hear why. The way the lions growl, the rustle of the tall grass—it’s visceral.

The production was actually a bit of a nightmare. They didn't film in Kenya due to tax reasons; they shot in South Africa at the Songimvelo Game Reserve. The crew dealt with snake bites, scorpion stings, and literal lightning strikes. It’s almost like the land itself was resisting the movie just like the lions resisted the bridge.

The lions used in the film weren't maneless like the real ones. They were "Bongo" and "Caesar," two trained lions from Ontario, Canada. Ironically, they were chosen because they were the least aggressive lions available.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans

If you're fascinated by this story, don't just stop at the movie. Here is how you can dive deeper into the real history:

- Visit the Chicago Field Museum: If you're ever in the Windy City, go see the actual lions. They aren't huge taxidermy mounts like you’d expect; Patterson originally kept them as floor rugs for 25 years before selling them to the museum. They were reconstructed, so they look a bit smaller than the movie versions, but seeing their skulls and the damage to their teeth makes the story feel very real.

- Read Patterson’s Book: The Man-Eaters of Tsavo is public domain. It’s a classic adventure memoir, though you have to take his "heroic" narrative with a grain of salt. It reads like an old-school thriller.

- Check out the Science: Look up the 2024 genomic studies by the University of Illinois. They recently extracted DNA from the hairs still stuck in the lions' teeth to see exactly what they ate in their final weeks. It’s some CSI-level wildlife biology.

Ultimately, this Val Kilmer movie about lions remains a cult classic because it taps into a primal fear. It’s about the moment our technology and our "civilization" fail us, and we’re left in the dark with something that is faster, stronger, and much hungrier than we are.

To explore more about the history of the Uganda-Mombasa Railway or the specific biology of Tsavo lions, you can research the 1898 East African labor strikes that were caused directly by these attacks.