Milton Bradley was a desperate man when he invented the game of life board. It was 1860. Abraham Lincoln was about to be elected. Bradley was a lithographer whose business had just collapsed because he’d printed a portrait of Lincoln without his trademark beard. Suddenly, the "clean-shaven" prints were worthless. He needed a win. He took a piece of checkered board, some red and ivory pieces, and created "The Checkered Game of Life." It wasn't about retirement or "winning" a house in the suburbs. It was about not dying in the "Suicide" or "Intemperance" squares.

Life is messy. This board game is, too.

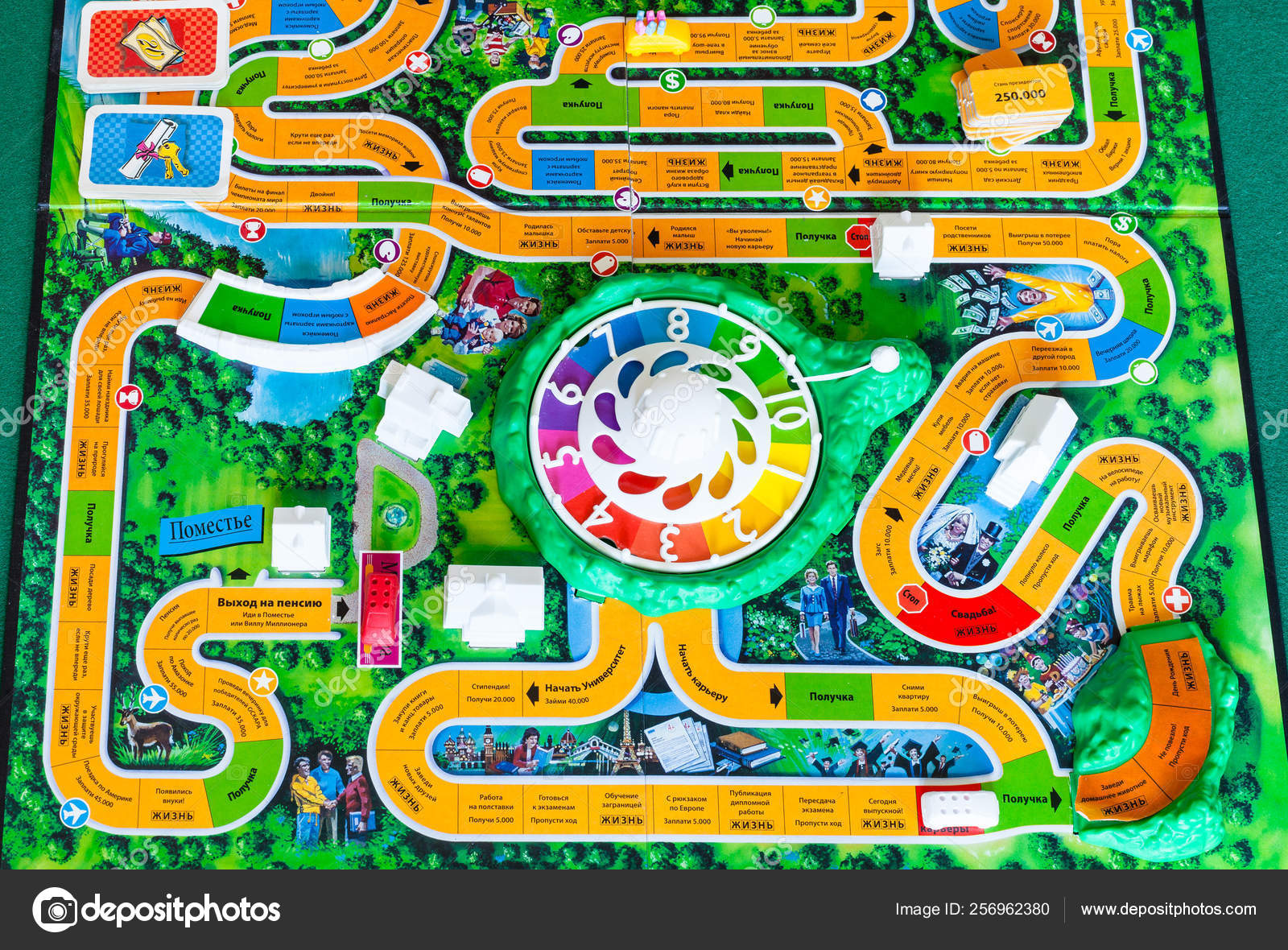

Most people think of the game of life board as that 1960s plastic-heavy classic with the rainbow spinner and the little pink and blue pegs. You know the one. You drive a station wagon, you get a job as a doctor, and you hope you don't run out of money before you hit Millionaire Acres. But that version is actually a massive pivot from the original vision. The game has survived for over 160 years because it constantly changes its skin to match whatever the "American Dream" looks like at the moment. In the 1800s, the dream was simply not being a drunk. In the 1990s, it was about recycling and buying a minivan. Today, it’s about pet insurance and massive debt.

The Dark Roots of the Game of Life Board

The original 1860 version was a morality play. Honestly, it was kind of depressing. You didn't spin a wheel; you used a teetotum (a six-sided top) because dice were associated with gambling and the devil. If you landed on "Bravery," you moved up. If you landed on "Idleness," you went to "Poverty." If you landed on "Perjury," you went straight to "Prison." There was no finish line labeled "Retirement." The goal was to reach "Happy Old Age." It was a reflection of Victorian values where character was more important than cash flow.

Milton Bradley sold 45,000 copies in the first year alone. That was huge for the mid-19th century.

Fast forward to 1960. It’s the game’s 100th anniversary. The Milton Bradley Company hires Reuben Klamer to "modernize" it. Klamer, along with Art Linkletter (a huge TV personality back then), basically threw the morality stuff out the window. They kept the name but changed the vibe entirely. This is where we got the 3D board, the mountains, the bridges, and that iconic clicking spinner. It became a game about accumulation. Success wasn't about being "virtuous" anymore; it was about having the most money when the game ended. This version is what most of us grew up with. It’s the version that defined what a "board game" was for generations.

Why the Spinner is Actually a Mathematical Nightmare

Let’s talk about that spinner. It’s the heart of the game of life board. It’s also incredibly frustrating. Unlike a pair of dice, which follows a bell curve (you’re most likely to roll a 7), the spinner is a flat probability. You have a 1 in 10 chance of hitting any number. This makes the game feel chaotic. You can't really strategize for a "likely" move. You’re just at the mercy of the plastic.

👉 See also: Dandys World Ship Chart: What Most People Get Wrong

Some people hate this. Critics often point out that the game of life board isn't really a "game" in the traditional sense because you make very few actual choices. You choose "College" or "Career" at the start. Maybe you choose to buy insurance. After that? You’re just a passenger in a plastic car.

But isn't that the point?

There’s a reason it resonates. Life often feels like that. You make one or two big decisions in your 20s, and then you’re just spinning the wheel and hoping you don't land on "Taxes" or "Mid-Life Crisis." The lack of agency in the game is its most realistic—and most cynical—feature.

Comparing the 1960 and 2020 Versions

If you look at a version from the late 20th century versus the ones sitting on Target shelves in 2026, the differences are wild.

- The 1960s/70s: You could literally "win" the game by becoming a Millionaire. The focus was on traditional roles. You got a spouse, you had kids (which were basically just pegs that took up space), and you bought a house.

- The Modern Era: Hasbro (which now owns Milton Bradley) has had to adapt. In the latest versions, you don't just collect cash; you collect "Action Cards." These represent experiences. Hiking in the Alps. Starting a vlog. Adopting a shelter pet.

- The Debt Mechanic: Modern versions are much more forgiving of debt. In the old days, being "Bankrupt" was a quick way to lose. Now, the game uses "Promissory Notes" to keep you in the race. It’s a very 21st-century way of looking at finance.

The Strategy Nobody Tells You About

Wait. Is there strategy?

Sorta. If you’re playing the game of life board and you actually want to win, you have to look at the math of the College path. For decades, the consensus was: always go to college. In the game, college-track jobs (Physician, Lawyer) had much higher salary caps. You’d take the debt early, but the "Pay Day" squares would make up for it.

✨ Don't miss: Amy Rose Sex Doll: What Most People Get Wrong

However, in some newer editions, the "Career" path has been buffed. If you land on a few early Pay Days as an Athlete or a Mechanic, the compounding interest of having that cash early can sometimes outpace the Doctor who starts five turns behind. It's a risk-reward calculation.

Another tip? Always buy the house early. Real estate in the game of life board almost always appreciates. You buy a "Split Level" for 40k and sell it later for double. It’s one of the few places where the game mimics a reliable investment strategy.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Board Design

Have you ever noticed the "Life Tiles"? In the 1990s version, these were the little square cardboard pieces you’d stack upside down. They had random values on the back. People often forget to count these at the end, but they are usually the tie-breaker. You could have $500,000 in cash, but if your opponent has five Life Tiles representing "Discovered Cure for Common Cold" or "Saved a Whale," they’re going to smoke you.

The board itself is a literal "track." Unlike Monopoly, which is a loop, Life is linear. You cannot go back. This is a deliberate design choice that has stayed consistent since Milton Bradley's original sketch in 1860. The "Day of Reckoning" at the end of the board is the final filter. You either go to Millionaire Estates or Countryside Acres.

It's worth noting that the "Country Side" used to be called the "Poor Farm" in the very early days. We’ve definitely gotten more polite as a society, even if our board games are still about beating our friends.

Real-World Impact and Rare Editions

Collectors actually hunt for specific versions of the game of life board. The most valuable isn't necessarily the oldest. The "Art Linkletter" 1960 edition in pristine condition is a holy grail for some. There are also weird spin-offs:

🔗 Read more: A Little to the Left Calendar: Why the Daily Tidy is Actually Genius

- The Simpsons Edition: This one is actually highly rated by board game geeks (BGG) because it adds a layer of humor that fits the "randomness" of the game perfectly.

- Star Wars: A Jedi’s Path: Instead of a car, you move a Jedi. Instead of a career, you’re trying to not turn to the Dark Side.

- The Electronic Banking Version: This replaced the paper money with a credit card machine. It’s faster, but honestly, it loses the tactile satisfaction of holding a "50,000" bill.

Why We Keep Playing

We play it because it’s a shared language. Everyone knows the feeling of the spinner flying off the board and hitting a lamp. Everyone knows the "click-click-click" sound. It’s a low-stress way to simulate a high-stress concept: our own mortality and success.

The game of life board isn't a deep tactical simulation like Terraforming Mars or Settlers of Catan. It doesn't pretend to be. It’s a chaos engine. It’s a reminder that you can do everything right—go to college, buy the insurance, drive the speed limit—and still get hit with a "Tornado" card that wipes out your savings.

That’s not "bad game design." That’s life.

How to Get the Most Out of Your Next Game Night

If you’re pulling the game out of the closet this weekend, don't just play by the boring rules. The game of life board is best when it's treated like a story-telling engine rather than a competitive sport.

- Roleplay the pegs. Give your kids names. Explain why your Accountant decided to buy a Luxury Yacht. It makes the "random" events feel more like a narrative.

- Check the Year. If you're playing an older set, look at the salaries. It's a hilarious time capsule. Being a "Doctor" and making $20,000 a year feels like a cruel joke in 2026, but in 1960, that was living like a king.

- House Rules. A popular one is the "Insurance Pool." Everyone puts $5,000 in a pot at the start. If someone hits a "Car Accident" or "House Fire," they take the pot instead of paying the bank. It adds a weirdly socialist layer to a very capitalist game.

The next time you look at the game of life board, remember it started as a way to tell people not to lie or steal. Now it's a way to see who can hoard the most colorful pegs. Both versions tell us a lot about who we are.

Actionable Insights for Game Owners:

- Maintenance: If your spinner is sticking, don't use WD-40. It degrades the plastic. Use a tiny drop of silicone-based lubricant or just clean the center pin with a dry cotton swab.

- Investment: If you find a 1960s version at a garage sale for under $20, buy it. Even if you don't play it, the 3D terrain pieces are often used by hobbyists for custom wargaming maps.

- Rule Clarification: Remember that in most versions, you must stop at the "Get Married" and "Buy a House" squares, even if you have moves left. Skipping these is the most common "illegal" move that ruins the game's economy.