Rome was sweltering. It was June 1963, and the air in St. Peter’s Square felt thick, heavy with the scent of incense and the collective breath of a million people who had descended on the Vatican. They weren't just there for a ceremony. They were there to say goodbye to "Il Papa Buono"—the Good Pope. When you look back at the funeral of Pope John XXIII, it’s easy to get lost in the sea of red vestments and the rigid protocols of the Catholic Church. But honestly, the atmosphere was less like a state funeral and more like a family grieving a grandfather.

He was 81. He had changed everything.

People forget how much of a shock his papacy was. Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was supposed to be a "caretaker" pope, a placeholder who wouldn't rock the boat while the cardinals figured out a long-term plan. Instead, he threw the windows open. He called the Second Vatican Council. He talked to prisoners. He joked about his own weight and his "large ears." So, when stomach cancer finally took him on June 3, 1963, the grief wasn't just formal. It was visceral.

The Chaos and the Quiet of the Vatican Grottoes

The transition from a living pope to a dead one is a bizarre, ancient process. For John XXIII, it started in the Apostolic Palace. There’s this old tradition—though some historians debate if it was actually used for him—where the Camerlengo (the Chamberlain) taps the Pope’s forehead with a silver hammer and calls his baptismal name three times. "Angelo, Angelo, Angelo." No response. The Ring of the Fisherman is smashed. The transition of power begins, but for the public, the focus was entirely on the body of the man who had tried to modernize a two-thousand-year-old institution.

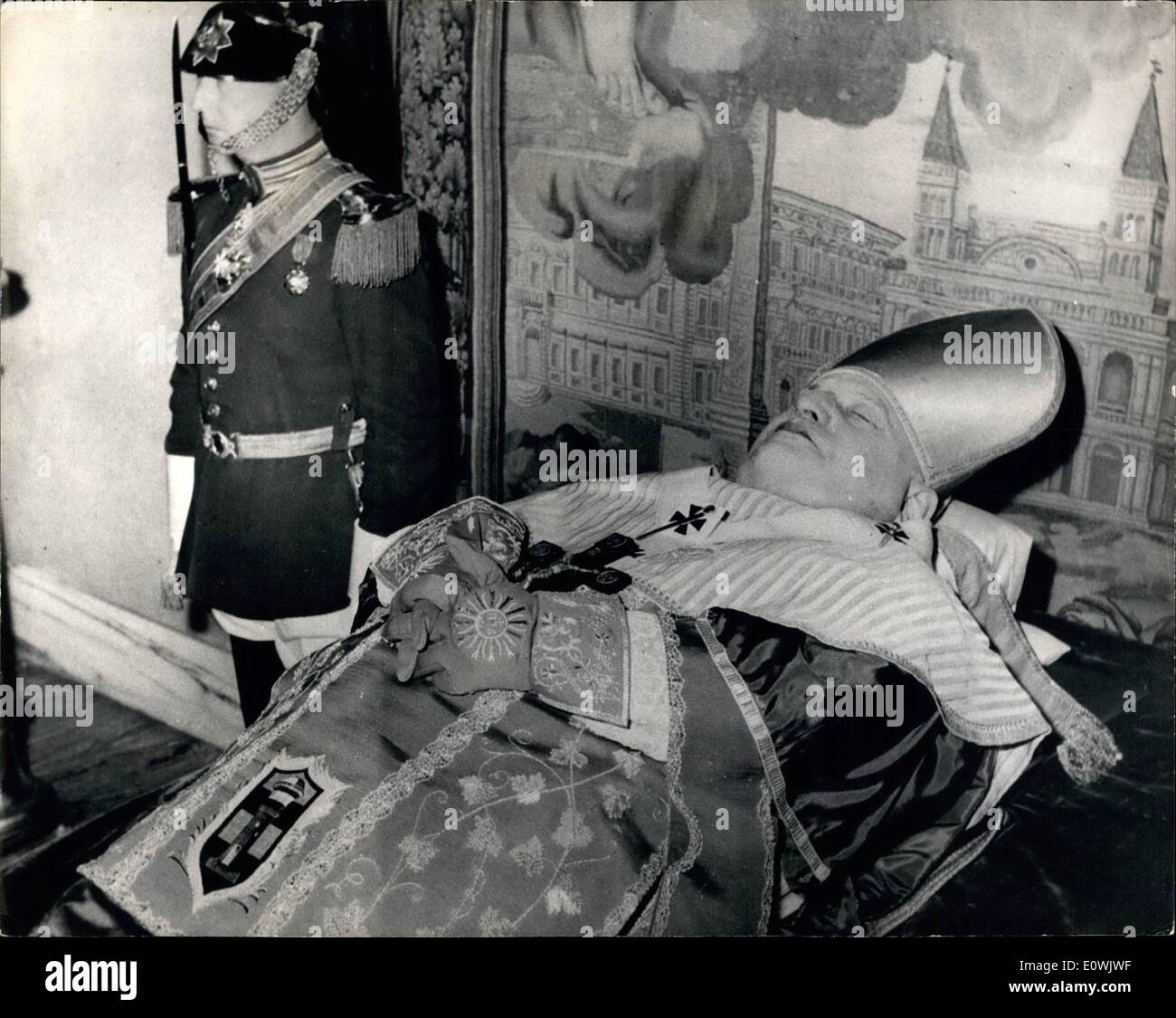

He lay in state. That’s a dry way of saying his body was placed on a high catafalque in St. Peter's Basilica so a never-ending line of people could shuffle past.

It lasted for days.

The line stretched back through the streets of Rome, snaking around the Tiber. People waited for six, eight, ten hours just for a three-second glimpse of the man in the red hat. You have to realize that in 1963, the world was in the middle of the Cold War. John XXIII had just helped mediate the Cuban Missile Crisis months earlier. He was a global rockstar of peace. The crowd wasn't just Catholics; it was everyone.

Why the preservation mattered

One detail that often gets glossed over in the history books is the embalming. It wasn't perfect, or at least, it wasn't meant to be permanent. But when they exhumed him decades later for his beatification in 2001, his body was remarkably well-preserved. People called it a miracle. Scientists pointed to the lack of oxygen in the triple-sealed lead, zinc, and oak coffins. Either way, the physical presence of John XXIII has always been a major part of his legacy.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The Ritual of the Three Coffins

The funeral of Pope John XXIII followed a rite that feels like something out of the Middle Ages. It’s a nesting doll situation. First, the body is placed in a cypress wood casket. This represents the Pope’s humanity. He’s just a man, made of earth. Inside that casket, they tuck a parchment record of his life (a rogito) and a bag of coins minted during his reign.

Then it gets heavy.

The cypress casket is soldered into a second casket made of lead. This is the one that really does the work of preservation. It’s heavy, somber, and bears his coat of arms. Finally, that whole massive weight is lowered into a third casket of elm or oak.

- Cypress: The human element.

- Lead: The durability of the office.

- Elm: The dignity of the sovereign.

Watching the crane lower these coffins into the crypt is a sobering sight. It’s the finality of it. The "caretaker" who changed the world was being tucked away under the floorboards of history, right near the tomb of St. Peter himself.

A Funeral Interrupted by a Council

There was a massive elephant in the room during the funeral: Vatican II.

The Council was halfway finished. John had started this massive meeting to "aggiornamento" (bring up to date) the Church, but he didn't live to see it finish. There was a real fear in the air. Would the next guy shut it down? Would the reforms die with the man? You could feel that tension in the way the Cardinals looked at each other during the funeral Mass.

The funeral wasn't just a burial; it was a transition of an era.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Cardinal Eugene Tisserant, the Dean of the College of Cardinals, led the rites. He was a bearded, imposing figure who looked like he belonged in a Byzantine mosaic. The Gregorian chant echoed off the Michelangelo-designed dome. Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine. Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord. It was beautiful, sure, but the vibe was "What do we do now?"

Comparing John’s Send-off to His Successors

If you compare John XXIII’s funeral to, say, John Paul II’s in 2005, the differences are wild. John Paul II’s funeral was the first great media event of the digital age. It was sleek. It was broadcast in high definition. John XXIII’s funeral was grainy, black-and-white, and felt much more "Old World."

Yet, the 1963 event had something the later ones lacked: a sense of genuine surprise.

Nobody expected to love John XXIII. They expected a boring old man. When he died, the world realized it had lost a moral compass it didn't know it needed. That’s why the funeral felt so heavy. It wasn't just the end of a reign; it was the potential end of a dream for a more open Church.

The location shift

Interestingly, John XXIII isn't actually in the grottoes anymore. If you go to St. Peter's today, you won't find him in the dark basement with the other popes. After he was beatified, his body was moved up into the main basilica. He’s now visible in a glass casket under the Altar of St. Jerome. He’s right there. You can see his face, preserved and serene. It’s a bit macabre for some, but for others, it’s a way to keep the "Good Pope" close.

What Most People Get Wrong About the 1963 Rites

One big misconception is that the funeral was "modern" because he was a modernizer. Nope. It was deeply traditional. The Mass was in Latin. The ritual was strict. The Church doesn't change its funeral rites just because the guy in the box liked to crack jokes.

Also, people think he died suddenly. He didn't. He suffered for months with a stomach hemorrhage. By the time the funeral happened, the Vatican had been on "death watch" for weeks. The tension had been building like a pressure cooker. When the white curtains were finally drawn across the windows of his study, the city of Rome basically stopped breathing.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Why We Still Talk About This Funeral Decades Later

You’d think a funeral from the 60s would be a footnote. But the funeral of Pope John XXIII remains a touchstone because it represents the "last of the old" and the "first of the new." He was the last pope to be buried with the full, unironic weight of the old monarchical papacy, yet he was the man who had effectively dismantled that very monarchy.

It’s that paradox that makes it fascinating.

If you’re researching this for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, you have to look at the photos of the Swiss Guard standing watch. They look like they’re guarding a fortress that’s already been breached—not by an enemy, but by the kindness of the guy inside.

Key Takeaways for History Enthusiasts

To truly understand the weight of this event, you need to look beyond the basic dates and names. Here is how you can practically apply this knowledge if you are visiting the Vatican or studying the era:

- Visit the Altar of St. Jerome: Don't just stay in the nave of St. Peter's. Go to the right aisle. Seeing the "incorrupt" body (preserved through a mix of chemistry and environment) gives a much deeper connection to the history than any book can.

- Study the Rogito: If you can find translations of the parchment buried with him, do it. It’s the Church’s official "final word" on what a person accomplished. John's is particularly moving because it highlights his efforts for world peace during the nuclear age.

- Contrast the Imagery: Look at the footage of his funeral and then look at the footage of the opening of Vatican II. The funeral is the "full stop" at the end of a very long sentence that he started.

- Research the "Caretaker" Myth: Use this event as a jumping-off point to study the Conclave of 1958. It proves that in history, "temporary" solutions often become the most permanent changes.

The funeral ended with the heavy thud of the stone slab being moved into place. But as any historian will tell you, the "Good Pope" didn't stay quiet for long. His influence over the next forty years of global religion was louder than any funeral bell.

To explore the physical legacy further, your next step should be a deep dive into the 2001 exhumation reports, which detail the state of the body and the specific preservation techniques used by the Vatican's medical team in 1963. This provides the scientific context to the "miracle" narratives often found in religious texts.