It was 1850. The United States was a powder keg, and Congress basically decided to toss a lit match into the center of it. People often talk about the Civil War as this inevitable clash over abstract ideas, but if you want to find the specific moment where the "cold war" between the North and South turned into a house on fire, you have to look at the fugitive slave law.

Most people think they know what it was. A law to catch runaways, right? Sorta. But it was actually much more sinister than that. It wasn't just about "reclaiming property." It was a legal sledgehammer that forced every single person in the North—whether they were a staunch abolitionist or someone who didn't care about politics at all—to become an active participant in the system of slavery.

Imagine you're walking down a street in Boston. You see a man being dragged away in chains. Under this law, if a federal marshal told you to help him secure those chains, you couldn't say no. If you refused, you were a criminal. That’s the reality of what this legislation did. It didn't just protect slavery in the South; it nationalized it.

The Compromise That Broke Everything

To understand what was the fugitive slave law, you have to look at the mess that was the Compromise of 1850. California wanted to enter the Union as a free state. The South was losing its mind because that would tip the balance of power. So, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster—the "giants" of the Senate—cooked up a deal. The North got California; the South got a brand-new, terrifyingly effective way to hunt down people who had escaped to freedom.

The 1793 version of the law already existed, but it was weak. Northern states had passed "Personal Liberty Laws" that basically gave the middle finger to Southern slave catchers. They required jury trials. They forbade state officials from helping. The 1850 version changed the game.

It created federal commissioners who had more power than most judges. These guys were the ultimate "pay-to-play" officials. Here is the part that sounds like a conspiracy theory but is 100% historical fact: if a commissioner decided a person was a "fugitive," he was paid $10. If he decided they were free and let them go, he was only paid $5. The law literally incentivized kidnapping.

No Trial, No Testimony, No Chance

This is where it gets really dark. If you were an African American living in Philadelphia or New York, you had zero rights under this law. You couldn't testify in your own defense. You didn't get a jury. A white person just had to show up, point a finger, and say, "That person belongs to me," or "That person belongs to my neighbor."

The word of a slaveholder was treated as absolute truth. The word of the accused meant nothing.

It created a state of constant terror. This didn't just affect people who had recently escaped. It targeted people who had been living free for twenty or thirty years. It targeted people who had been born free. Because there was no due process, a "commissioner" could simply sign a paper and send a free-born Northern citizen into the cotton fields of Georgia.

💡 You might also like: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

Honestly, it was a kidnapper’s dream.

The Case of Anthony Burns

If you want to see how this played out in the real world, look at Anthony Burns. In 1854, Burns was living in Boston, having escaped from Virginia. When he was captured, the city went into a full-blown riot. Abolitionists tried to storm the courthouse to break him out. One deputy was killed.

The federal government’s response? President Franklin Pierce sent in the U.S. Marines. They marched Burns through the streets of Boston to a ship waiting to take him back to Virginia. Thousands of Bostonians lined the streets, hissing and groaning, draping their windows in black coffins. It cost the government roughly $40,000 to return one man to slavery. In 1850s money, that was a fortune.

This is a key point: the law didn't make the South feel more secure. It made the North realize that they were no longer living in "free states." They were living in a country where the federal government was the enforcement arm of the plantation.

The Death of Neutrality

Before 1850, a lot of Northerners were "middle of the road." They didn't like slavery, but they didn't want to start a war over it. They figured it was a "Southern problem."

The fugitive slave law killed that mindset.

When the law required "all good citizens" to assist in the capture of escapees, it forced people to choose. Do you follow the law, or do you follow your conscience? For many, the answer was radicalization.

- The Underground Railroad went from a secret network to a much more aggressive operation.

- Vigilance Committees formed in cities like Detroit and Syracuse to physically fight off slave catchers.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe was so enraged by the law that she sat down and wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

If you’ve ever wondered why that book became the biggest bestseller of the century, this law is the reason. People were hungry for a way to express the moral outrage they felt watching their neighbors being dragged away in broad daylight.

📖 Related: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

Judicial Overreach and "States' Rights" Irony

There’s a massive irony here that historians like Eric Foner often point out. We usually hear that the South was the champion of "states' rights." But the fugitive slave law was the most massive expansion of federal power in the 19th century.

Southern politicians demanded that the federal government override Northern state laws. They wanted federal marshals to have the power to ignore local police. They wanted federal courts to bypass local juries. When it came to protecting slavery, the South was perfectly happy with a massive, intrusive federal government.

This created a legal paradox. Northern states, the ones we usually think of as favoring a strong federal government, started arguing for states' rights to protect their citizens from federal slave catchers. The roles were completely flipped.

The Wisconsin Rebellion

In 1854, a man named Joshua Glover was rescued from a jail in Milwaukee by a mob of 5,000 people. The guy who led the rescue, Sherman Booth, was arrested for violating the federal law. The Wisconsin Supreme Court did something wild: they declared the fugitive slave law unconstitutional.

They basically told the U.S. Supreme Court to pound sand. This led to a massive legal showdown (Ableman v. Booth) where the U.S. Supreme Court eventually slapped Wisconsin down, asserting that federal law is the supreme law of the land.

The tension was becoming unbearable. You had states openly defying the federal government, not over taxes or trade, but over the basic humanity of the people living within their borders.

A Legacy of Resistance

So, what happened? Did the law work?

Technically, yes. Hundreds of people were returned to the South. Thousands more fled to Canada. If you look at the census data from the 1850s, the Black population in many Northern cities actually dropped because people were terrified of being kidnapped.

👉 See also: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

But in a larger sense, it was a total failure for the South. Instead of "settling" the slavery question, it proved to the North that the "Slave Power" (as they called it) would never be satisfied. It convinced people like Abraham Lincoln that the house really was divided and couldn't stand that way much longer.

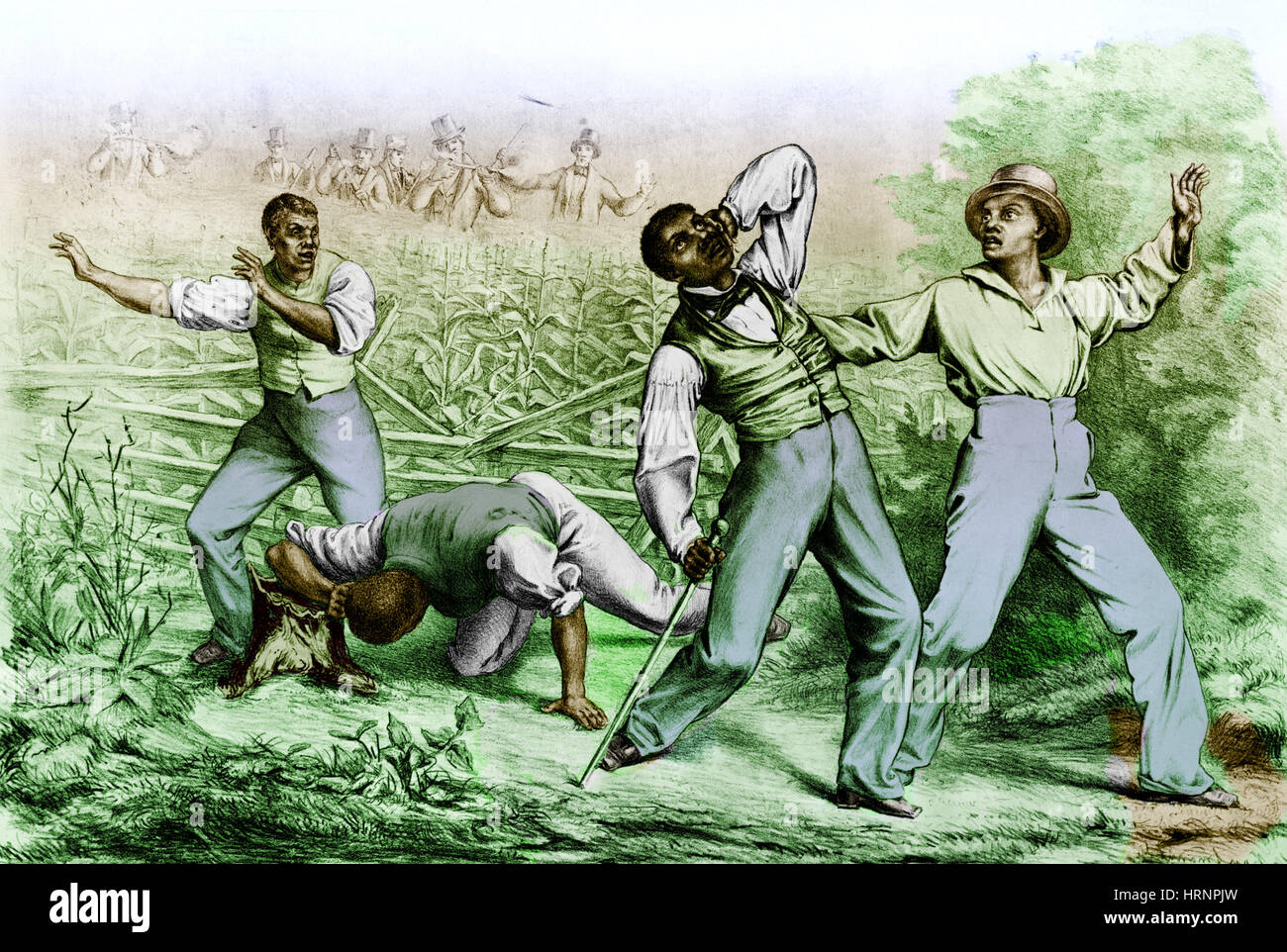

It’s also important to remember the people who fought back. This wasn't just about white abolitionists in Boston. It was about people like Shadrach Minkins, who was rescued from a courtroom in a daring daylight raid by Black activists. It was about families who slept with shotguns by the door, ready to defend their freedom because the law of the land wouldn't.

How to Engage with This History Today

Understanding the fugitive slave law isn't just about memorizing a date in a history book. It’s about understanding how laws can be used to weaponize the citizenry against one another. If you want to dive deeper into this or see the impact for yourself, there are a few things you can do.

Visit a National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site. These aren't just museums; many are actual houses and locations where the resistance to this specific law took place. The Christiana Riot site in Pennsylvania is a heavy one—it’s where a group of freedom seekers fought a literal battle against a slaveholder and won.

Read the actual text of the 1850 Act. It’s dry, legalistic, and terrifying. Seeing the specific language used to describe human beings as "services or labor" helps you realize how the law was used to strip away personhood.

Look into the records of your own city. Many people are surprised to find that their own "quiet" Northern town had a Vigilance Committee or a safe house. The local history is often much more radical than what we learned in 8th grade.

The reality is that the fugitive slave law was the beginning of the end. It proved that compromise was no longer possible. When a law demands that you choose between being a good citizen and being a good person, the system is already broken. All that was left was the smoke.