It was a disaster. Honestly, there’s no other way to describe the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 without acknowledging that it was one of the most hated, violent, and legally aggressive pieces of legislation ever passed by the U.S. Congress. If you were living in a Northern city like Boston or Philadelphia in the early 1850s, your world changed overnight. Suddenly, your neighbor—the guy who had lived down the street for a decade, raised a family, and worked in the local shop—could be snatched off the street by a federal marshal and dragged into a "court" that wasn't really a court at all.

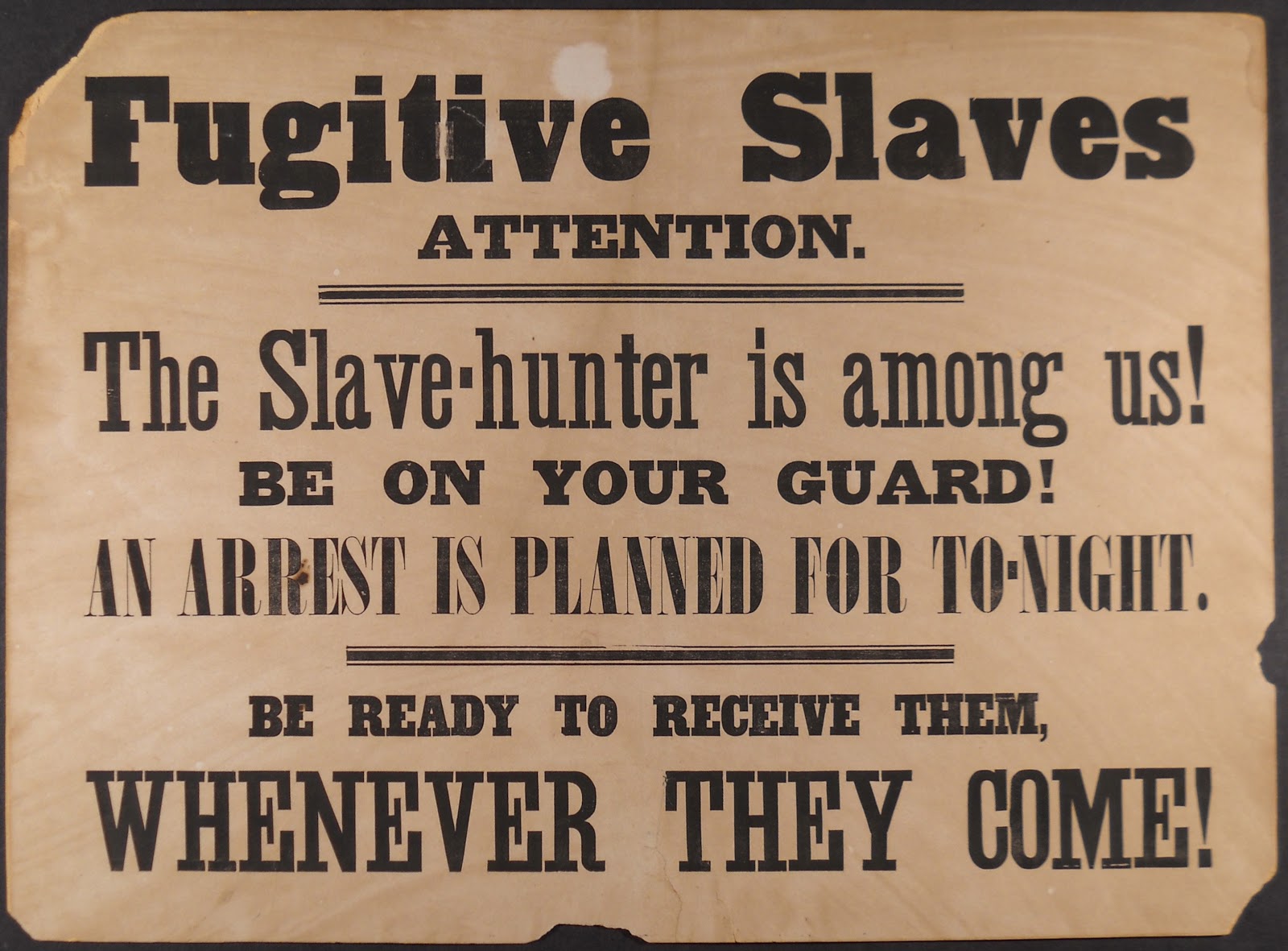

Most people think of the Underground Railroad as this secret, quiet network of tunnels and nighttime escapes. But after the Fugitive Slave Act dropped, that struggle moved right into the middle of the town square. It wasn't quiet anymore. It was a brawl.

Why the Compromise of 1850 Was a Deal with the Devil

To understand the Fugitive Slave Act, you have to look at the mess that was American politics in 1850. The country was basically tearing itself apart over whether the new territories won in the Mexican-American War would allow slavery. California wanted in as a free state. The South was threatening to walk out—literally secede—if the balance of power shifted.

Enter Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. They hammered out the "Compromise of 1850."

California got its statehood as a free state. The slave trade was banned in Washington, D.C. But the South demanded a massive, ugly concession in return: a strengthened, "ironclad" law to reclaim people who had escaped slavery. This wasn't the first law of its kind—there was an older version from 1793—but the 1850 version was the 1793 law on steroids. It was designed to be impossible to ignore.

The Brutal Mechanics of the Law

The Fugitive Slave Act basically turned every American citizen into a potential deputy for slave catchers. That sounds like an exaggeration, but it's literally what the text of the law required.

💡 You might also like: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

Here is how the system actually worked, and it's terrifying. Federal commissioners were appointed to handle these cases. If a slaveholder or a "slave catcher" claimed a Black person was a runaway, they brought them before this commissioner.

There was no jury.

The accused person could not testify.

They had no right to a lawyer in the way we think of it today.

Basically, if a white man showed up with an affidavit—a piece of paper—saying "this person belongs to me," that was usually the end of the story. But here is the part that really proves how corrupt the system was: the pay scale. The commissioner was paid $10 if he ruled in favor of the slaveholder, but only $5 if he ruled that the person was free. The government literally built a financial incentive for kidnapping into the law.

The "Posse Comitatus" Clause

This is the part that radicalized the North. The law stated that federal marshals could "summon and call to their aid the bystanders." This meant that if you were a white Northerner who hated slavery, a federal agent could legally force you to help catch a runaway. If you refused? You could be fined $1,000—a massive fortune back then—and thrown in jail for six months.

It turned the entire North into a hunting ground.

📖 Related: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

The Case of Anthony Burns: A City Under Siege

If you want to see what the Fugitive Slave Act looked like in practice, look at what happened to Anthony Burns in 1854. Burns had escaped from Virginia and was living in Boston. He was working at a clothing store when he was grabbed by federal agents.

Boston went absolutely wild.

A mob of abolitionists, led by men like Thomas Wentworth Higginson, tried to storm the courthouse to break him out. A deputy was killed in the chaos. President Franklin Pierce, wanting to prove he could enforce the law, sent in federal troops.

When Burns was marched down to the harbor to be sent back to Virginia, the streets of Boston were lined with thousands of people hissing and screaming "Shame!" The government spent about $40,000 to return one man to slavery—a man whose "market value" at the time was maybe $1,200. It showed that the Fugitive Slave Act wasn't just about labor; it was about the South asserting total dominance over Northern law.

Why the Law Backfired on the South

The irony of the Fugitive Slave Act is that it actually accelerated the start of the Civil War. Before 1850, many Northerners were "anti-slavery" in a vague way but didn't want to get involved. They thought it was a Southern problem.

👉 See also: When Does Joe Biden's Term End: What Actually Happened

The 1850 law made it a Northern problem.

- It forced regular people to witness the brutality of the system on their own doorsteps.

- It led to the passage of "Personal Liberty Laws" in Northern states, which were basically state-level attempts to ignore or block the federal law.

- It inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She was so incensed by the law that she wrote the book to show the North what slavery actually looked like.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, usually a pretty calm philosopher, wrote in his diary: "This filthy enactment was made in the nineteenth century by people who could read and write. I will not obey it, by God."

The Legal Legacy and the Path to War

The Supreme Court eventually weighed in with the Ableman v. Booth decision in 1859, asserting that federal law (the Fugitive Slave Act) trumped state laws. This created a massive "states' rights" paradox. Historically, we're taught that the South was the champion of states' rights. But in the 1850s, the South was the one demanding that the federal government use its power to override Northern state laws.

The North, meanwhile, was arguing for the right to protect its own citizens from federal overreach.

By the time 1860 rolled around, the trust between the North and South was completely gone. The Fugitive Slave Act had proven to the North that the "Slave Power" would never be satisfied, and it proved to the South that the North would never truly respect their "property" rights.

Actionable Insights: Understanding the Impact Today

When you look back at the Fugitive Slave Act, don't just see it as a dry historical date. See it as a lesson in how law can be used as a weapon against human rights.

- Research the "Personal Liberty Laws": Look into how states like Vermont and Wisconsin tried to nullify federal law. It’s a fascinating look at the early legal battles over federal vs. state power.

- Visit the Sites: If you’re ever in Boston, visit the site of the Anthony Burns riot near Court Street. Seeing the geography of where these battles happened makes the history feel much more visceral.

- Read Original Narratives: Instead of just reading history books, look for the accounts of people like Jermain Loguen or Shadrach Minkins—men who actually dealt with the terror of being hunted under this law.

- Evaluate Modern Legal Parallels: Think about how "mandatory assistance" laws or federal mandates still spark the same kinds of "states' rights" debates today. The tension between local conscience and federal authority started right here.

The law wasn't finally repealed until 1864, well into the Civil War. By then, the world it helped create had already burned down.