When you think about the legal machinery that kept slavery alive in the United States, your mind probably jumps straight to 1850. You think of the Great Compromise, Daniel Webster, and the literal brink of the Civil War. But the real structural damage started much earlier. Most people don’t realize that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was the original blueprint for state-sponsored kidnapping. It wasn’t some obscure footnote. It was a massive, sweeping piece of legislation that George Washington himself signed into law, and it basically turned every state—even the "free" ones—into a hunting ground.

The 1793 law was short. Barely four sections long. Yet, those few paragraphs did more to destabilize the lives of Black Americans than almost any other early federal statute. It created a legal bypass that allowed slave catchers to skip over the rights of the accused entirely. No jury. No testimony from the person being seized. Just a single magistrate’s word. It was brutal.

How the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 Actually Worked

The law was born out of a specific 1788 dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia. A free Black man named John Davis was kidnapped in Pennsylvania by three Virginians. When Pennsylvania tried to extradite the kidnappers, Virginia refused. The governors argued. The Continental Congress hemmed and hawed. Eventually, the federal government decided they needed a uniform way to handle "refugees from justice" and "persons escaping from service."

That phrase—"persons escaping from service"—is the legal euphemism that changed everything.

Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, a slaveholder or their hired "agent" could simply cross state lines, seize a person, and bring them before a federal judge or even just a local town magistrate. All they needed was an oral affidavit or a paper certificate from the slaveholder’s home state. That’s it. One person’s word against another’s existence. If the magistrate was satisfied, they issued a certificate of removal.

Honestly, the lack of due process was staggering. The person being claimed as "property" had zero right to testify in their own defense. Think about that for a second. You’re living your life in Philadelphia or Boston, maybe you’ve been free for ten years, and suddenly a stranger grabs you, takes you to a local official, and within twenty minutes, you’re being hauled back to a plantation in Georgia. The law even included a $500 fine for anyone who helped a fugitive or hindered their arrest. In 1793, $500 was an absolute fortune—equivalent to several years' salary for an average laborer. It was a massive deterrent designed to force the North into compliance.

The Problem with Local Magistrates

The 1793 Act was incredibly lazy in its execution, which made it dangerous. It didn't just use federal judges. It empowered "any magistrate of a county, city, or town corporate."

📖 Related: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

This meant slave catchers didn't have to find a high-level federal official. They could find the most biased, easily bribed, or indifferent local clerk in a small village and get their paperwork signed. There was no oversight. There was no central registry of who was being taken. It was a decentralized system of human trafficking authorized by the United States government. Historian H. Robert Baker has noted that this specific delegation of power to state officials actually became a major constitutional sticking point later on, because it essentially forced state employees to do the federal government's dirty work.

Why the North Fought Back (And Why It Failed)

You might assume the North just rolled over. They didn't. But their resistance created a legal "cold war" that lasted for decades. Northern states started passing "Personal Liberty Laws." These were local statutes designed to throw sand in the gears of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

Some states demanded a jury trial for anyone accused of being a fugitive. Others forbade state officials from helping slave catchers or banned the use of local jails to hold "captured" people. It was a game of legal cat-and-mouse.

One of the most famous clashes happened in the Supreme Court case Prigg v. Pennsylvania in 1842. Edward Prigg was a professional slave catcher who snatched Margaret Morgan from Pennsylvania to take her back to Maryland. Pennsylvania arrested Prigg for kidnapping. The case went all the way to the top. Justice Joseph Story wrote the opinion, and it was a weird, split decision. He said the federal law was constitutional and that states couldn't block it. But—and this is a huge "but"—he also said that state officials didn't have to help.

He basically said, "The federal government has the power to enforce this, so go ahead, but you can't force the state of Pennsylvania to pay for it or use its police to do it."

This led to a surge in specialized federal "commissioners," but it also emboldened abolitionists. They realized that if they made it expensive and difficult enough, they could effectively nullify the law on the ground.

👉 See also: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

The Human Cost: Real Stories of the 1793 Law

Statistics don't tell the whole story. The fear was visceral.

Take the case of Isaac Hopper, a Quaker in Philadelphia who became a sort of "legal eagle" for the Underground Railroad. He spent much of his life fighting the 1793 Act in courtrooms. He’d show up and demand that the slave catchers prove every tiny detail of their paperwork. He knew the law was rigged, so he used the law's own complexity against it.

Then there’s the reality of the "Reverse Underground Railroad." Because the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 made it so easy to claim someone was a slave, professional kidnappers started snatching free Black people who had never been enslaved in their lives. Solomon Northup, whose story became 12 Years a Slave, was a victim of this climate, though his kidnapping happened much later. The 1793 Act created the legal environment where Black skin was essentially a "guilty until proven innocent" badge in the eyes of the federal government.

It wasn't just about "slaves" escaping. It was about the fundamental insecurity of being Black in America. You could be a business owner, a parent, a pillar of your community, and a single piece of paper from a magistrate three states away could erase your life.

Comparisons with the 1850 Act

People often confuse the two laws. Here's the short version of the difference. The 1793 version was the "skeleton." The 1850 version was the "monster."

- The 1850 Act forced ordinary citizens to assist in captures. The 1793 Act didn't go that far.

- The 1850 Act paid magistrates $10 if they ruled for the slaveholder and only $5 if they ruled for the accused. The 1793 Act didn't have that blatant "bribe" structure.

- The 1850 Act eliminated the possibility of a "Personal Liberty Law" defense entirely.

But without the 1793 foundation, the 1850 Act never would have happened. The first law set the precedent that the federal government’s right to "property" outweighed a state’s right to protect its own residents.

✨ Don't miss: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

What Most People Get Wrong

The biggest misconception? That the 1793 Act was only about the South.

The North was deeply complicit. Many Northern businessmen, especially those in shipping and textiles, wanted the law enforced because they didn't want to upset their Southern trading partners. Cotton was king, even in New York and Rhode Island. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was as much about protecting the national economy as it was about "rights."

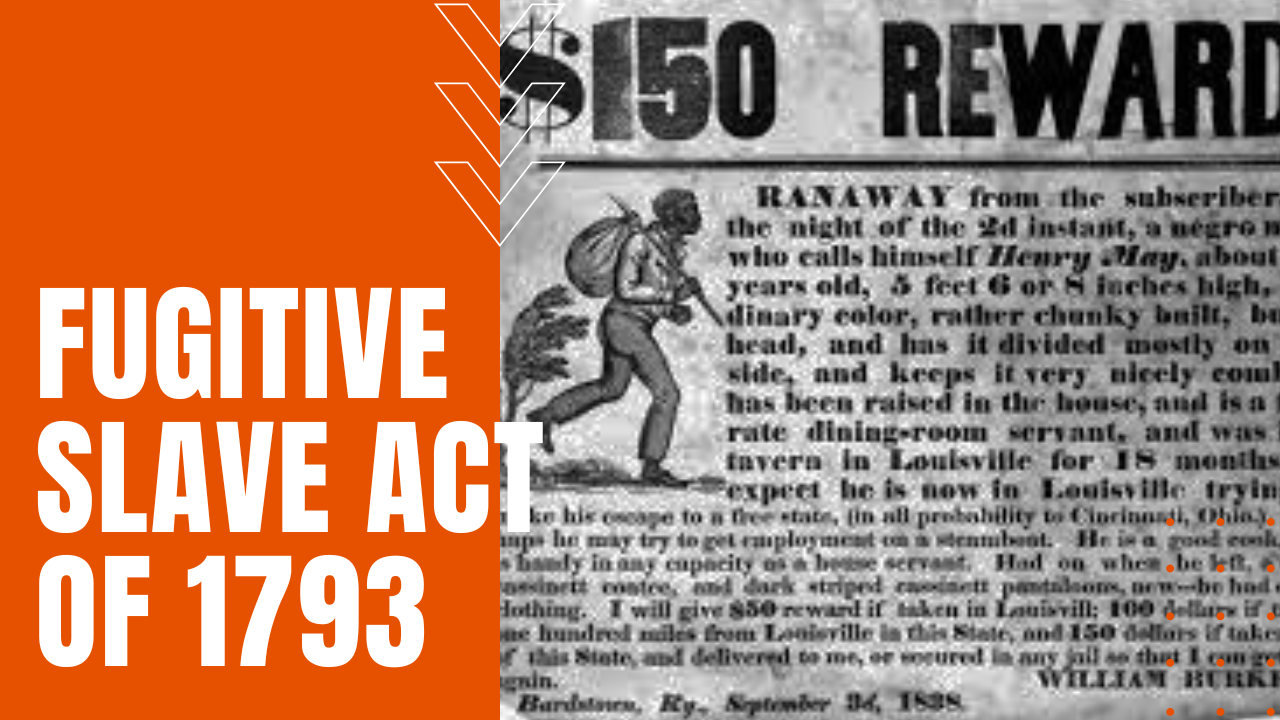

Also, it’s a mistake to think this law was rarely used. While we don't have a digital database of every capture, newspapers from the era are filled with notices of "returned" people. It was a constant, low-level hum of terror that existed for 60 years before the "big" law of 1850 ever touched the books.

Why This History Matters Today

Understanding the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 helps you understand the roots of American policing and the long history of due process disputes. It shows how easily "administrative" laws can be used to bypass fundamental human rights. It also highlights the power of state-level resistance to federal overreach—a theme that still dominates American politics.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into this or understand the legal ripple effects, here are some actionable ways to engage with the history:

- Visit the National Constitution Center’s digital archives. They have the original text of the 1793 Act and the 1788 letters that sparked it. Reading the actual language—the cold, clinical way they discuss human beings as "persons held to labor"—is eye-opening.

- Research "Personal Liberty Laws" in your own state. If you live in the Northeast or Midwest, your state likely had intense legal battles over the 1793 Act. Local historical societies often have records of "kidnapping" cases that occurred in your backyard.

- Track the evolution of the "Certificate of Removal." Compare the 1793 requirements to modern administrative warrants. You’ll see some scary parallels in how "summary proceedings" are still used in various parts of the legal system today.

- Look into the work of Eric Foner. His book Gateway to Freedom is basically the gold standard for understanding how the legal fight against these acts created the infrastructure of the Underground Railroad.

The 1793 Act wasn't a mistake or a glitch. It was a choice. It was a compromise made by the "Founding Fathers" to keep a fragile union together at the expense of millions of lives. Recognizing that reality is the only way to understand how the American legal system actually grew up. It didn't just happen; it was built, one certificate of removal at a time.