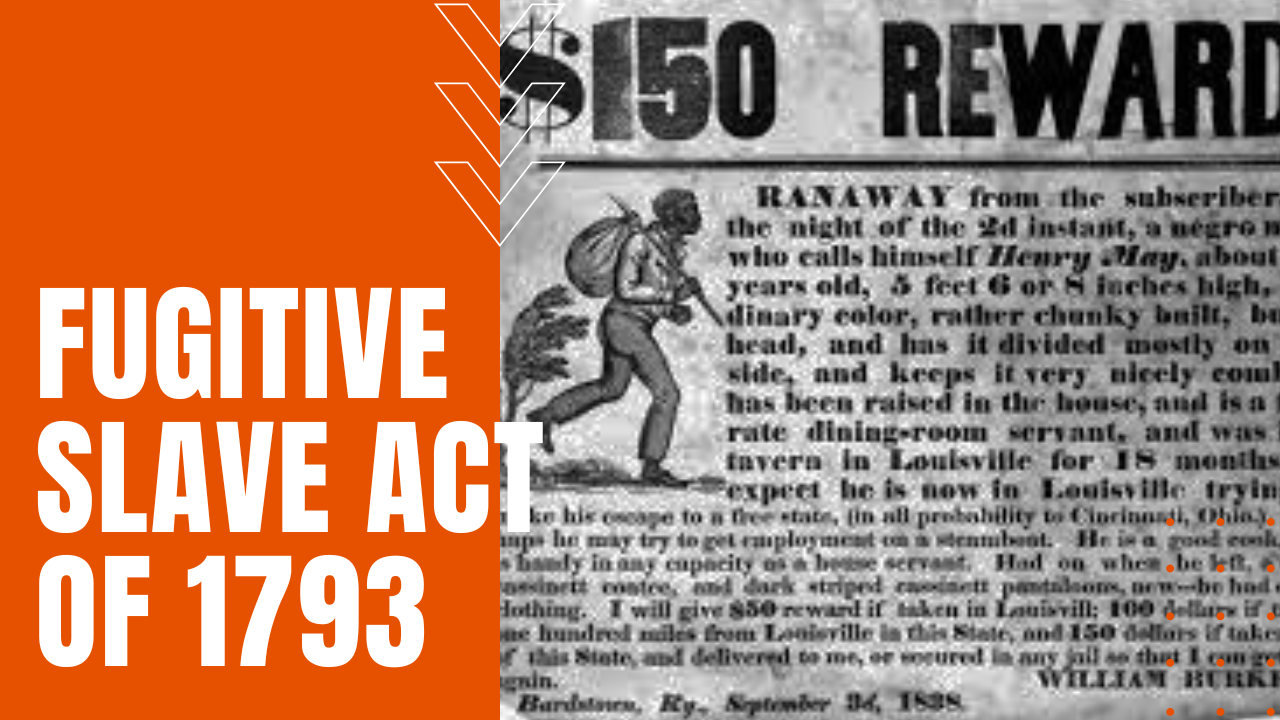

It’s easy to look back at the early days of America and think everything was a neatly organized debate between guys in powdered wigs. It wasn't. Honestly, the Fugitive Slave Act 1793 is the perfect example of how messy, desperate, and legally blurry the United States actually was just five years after the Constitution was ratified. You’ve probably heard of the 1850 version—the one with the massive protests and the "bloodhound bill" nickname—but the 1793 law was the spark that started the fire.

Most people think this law was just a natural extension of the Constitution. It wasn't that simple. Basically, the Founding Fathers had left a giant, gaping hole in the legal system. They wrote the "Fugitive Slave Clause" (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), but they didn't explain how it was supposed to work. Who pays for the slave catchers? Who proves someone is actually enslaved? Can a state just say no?

The Fugitive Slave Act 1793 was the federal government’s attempt to fix that. It failed. Spectacularly.

What Triggered the Fugitive Slave Act 1793?

It all started with a kidnapping in Pennsylvania. In 1791, three men from Virginia crossed the border into Pennsylvania and kidnapped a Black man named John Davis. They claimed he was a runaway. Pennsylvania officials were furious because their state laws protected free Black people, and they demanded Virginia extradite the kidnappers. Virginia’s governor basically told Pennsylvania to kick rocks.

George Washington had to step in. He saw that if states started fighting over "property" across borders, the whole Union would fall apart. So, he pushed Congress to pass a law that would give slave owners the legal right to cross state lines to recover people they claimed as property.

The resulting Fugitive Slave Act 1793 was surprisingly short. It was only four sections long. But those four sections changed everything.

Under this law, a slave owner (or their agent) could seize an alleged runaway anywhere in the country. They just had to bring that person before a federal judge or a local magistrate. No jury trial. No right to testify. Just a simple oral affidavit or a scrap of paper was enough to send someone back into a lifetime of bondage. It was a kangaroo court by design.

The Legal Loopholes That Created Chaos

You’d think a federal law would be the final word. Nope.

The 1793 law didn't actually require Northern state officials to help. It said they could help, but it didn't strictly penalize them if they just sat on their hands. This led to what we now call "Personal Liberty Laws." States like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts started passing their own laws to make it as difficult as possible for slave catchers to operate.

They required higher standards of proof. They gave people the right to a jury trial at the state level.

This created a legal nightmare. A slave catcher would show up with a warrant from the federal Fugitive Slave Act 1793, and a local sheriff would arrest him for kidnapping under state law. It was a jurisdictional war.

Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) eventually went to the Supreme Court to settle this. Justice Joseph Story wrote the opinion, and his ruling was kinda weird. He said that while the federal law was constitutional, state governments didn't have to use their own resources to enforce it. Basically, he told the South, "You have the right to catch your runaways, but you have to do the work yourself."

This is where the real tension built up. If the federal government couldn't force Northern states to help, the law was essentially toothless in many parts of the country.

Human Impact: The Reality of Being "Fugitive"

We often talk about these things as legal theories. They weren't theories to people like Oney Judge.

Oney Judge was enslaved by George and Martha Washington. In 1796, while the Washingtons were in Philadelphia, she simply walked out of the house while they were eating dinner and boarded a ship to New Hampshire. Washington was obsessed with getting her back. He used the Fugitive Slave Act 1793 to track her down. He sent agents to New Hampshire to try and trick her into coming back.

But here’s the thing: Judge had community support. The people in Portsmouth protected her. Even though the law was on Washington’s side, the "social atmosphere" of the North was becoming a wall that the law couldn't climb. Oney Judge died a free woman, never having returned to the Washington estate, despite the President's best efforts to use the law he had signed.

It wasn't just about famous people, though. For free Black people in Northern cities, the Fugitive Slave Act 1793 was a constant shadow.

The law made it incredibly profitable to kidnap free people. Since the law didn't require a jury, a "professional" kidnapper could grab someone off the street in Philadelphia, find a corrupt magistrate who would take a bribe, and be across the border into Maryland before anyone knew what happened. This gave rise to the "Reverse Underground Railroad," a terrifying network of kidnappers who used the 1793 law as a legal shield for human trafficking.

Why Does This Still Matter Today?

If you want to understand why states' rights and federal power are always at each other's throats, you have to look at this era.

The Fugitive Slave Act 1793 was one of the first major tests of the Supremacy Clause. It forced Americans to ask: Does a federal law override a state's right to protect its own residents? We're still asking that today about everything from immigration to environmental regulations.

Historians like Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Richard Newman have done incredible work digging into the records of this period. They've shown that the resistance to this law wasn't just coming from white abolitionists. It was being led by free Black communities who built their own legal defense funds and physical protection squads.

They didn't just wait for the law to change; they made the law impossible to enforce.

The Shift to 1850

Eventually, the South realized the 1793 law wasn't working. It was too easy for Northern states to ignore. This frustration simmered for decades until it boiled over into the Compromise of 1850.

The 1850 version was much more brutal. It created federal commissioners who were paid $10 if they ruled in favor of the slave owner and only $5 if they ruled in favor of the accused runaway. It also forced ordinary citizens to assist in captures or face prison time.

But you can't understand the anger of 1850 without seeing the "soft" failures of the Fugitive Slave Act 1793. The 1793 law proved that a law is only as good as the people willing to enforce it. When the North refused to comply, the South pushed for more power, and that escalation led directly to the Civil War.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're researching this or just want to get a better handle on the era, don't just read the Wikipedia summary.

- Read the Prigg v. Pennsylvania decision. It’s a dense read, but it shows exactly how the Supreme Court tried to balance federal power with state sovereignty. It’s the "missing link" between 1793 and 1850.

- Look into the "Personal Liberty Laws." Every Northern state had a different way of resisting. Massachusetts' version was very different from Pennsylvania’s. Seeing those differences helps you understand why the North wasn't a monolith.

- Check out the records of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. They were the ones on the ground fighting these cases in the 1790s. Their archives are a goldmine of real stories that go beyond the legal jargon.

- Trace the geography. Look at how close free states were to slave states. The "borderland" culture of places like Southern Ohio or Southeast Pennsylvania was incredibly tense because of this law.

The Fugitive Slave Act 1793 wasn't just a boring piece of paper. It was a spark. It was a source of terror for thousands. And it was the first real sign that the United States was a house divided against itself long before Lincoln ever said those words.