You’re basically standing over a pan of onions for forty-five minutes. That’s the reality. If a recipe tells you that you can achieve a deep, jammy, mahogany-colored base for french onion macaroni and cheese in fifteen minutes, they are lying to you. Purely. Chemically. Onions contain roughly 4% to 6% sugar by weight, and to get those sugars to undergo the Maillard reaction without burning the edges, you need low heat and an unreasonable amount of patience.

It's a weird hybrid dish. It takes the childhood comfort of boxed mac and the sophisticated, moody depth of a Parisian bistro soup and smashes them together. When it works? It’s arguably the best thing you’ll ever eat. When it fails, it’s just greasy noodles with some slimy, pale onions floating in the mix. Nobody wants that.

I’ve spent years tinkering with cheese ratios. Most people think more cheese equals better mac. Not true. If you overload the sauce with fat, it breaks. You end up with a puddle of oil at the bottom of the Dutch oven. You need a specific blend of Gruyère—because you need that nutty, Alpine funk—and a sharp, aged white cheddar to provide the acidic backbone that cuts through the sweetness of the onions.

The Science of the "Onion Jam"

The foundation of a great french onion macaroni and cheese isn't the pasta. It’s the Maillard reaction. We often confuse caramelization with the Maillard reaction, but they’re different. Caramelization is the pyrolysis of sugar, while the Maillard reaction involves amino acids and reducing sugars. In a heavy-bottomed skillet, these two processes work in tandem to create those complex, savory-sweet flavor compounds.

Don't use red onions. Just don't. They turn a weird, unappealing grey-purple when cooked down this long. Stick to yellow onions or Vidalia if you want a sweeter profile. You want to slice them pole-to-pole, not into rings. Why? Because the fibers run pole-to-pole. Slicing them this way helps the onion retain some structural integrity so it doesn't just turn into mushy paste during the baking process.

Julia Child famously suggested adding a pinch of sugar to help the process along, but if you’re using high-quality onions and keeping the heat at a steady medium-low, you don't really need the crutch. What you do need is deglazing. Every time a brown film (the fond) starts to build up on the bottom of your pan, splash in some dry sherry or beef stock. Scrape it up. That's the flavor. That's the soul of the dish.

Why Your Cheese Sauce Is Probably Breaking

It’s the heat. Or the pre-shredded cheese. Honestly, if you buy the bags of pre-shredded cheese from the grocery store, your french onion macaroni and cheese will never be elite. Those bags are coated in potato starch or cellulose to keep the shreds from sticking together. That starch prevents the cheese from melting into a smooth, cohesive emulsion. It makes the sauce gritty.

Buy the block. Grate it yourself. It’s a workout, sure, but the results are night and day.

💡 You might also like: How 2 Gums on 4C Transition Changes Everything for Hair Texture Management

The Bechamel vs. Mornay Debate

Technically, once you add cheese to a white sauce (bechamel), it becomes a Mornay sauce. For this specific dish, you want a slightly thicker Mornay than usual. You’re adding onions that still hold a bit of moisture, and if your sauce is too thin, the whole thing becomes soupy in the oven.

- Use whole milk. Skim has no place here.

- A pinch of ground nutmeg is non-negotiable. It doesn't make it taste like dessert; it highlights the earthiness of the Gruyère.

- Consider a teaspoon of Dijon mustard. It’s an emulsifier. It helps keep the fats and solids from separating.

The Pasta Selection Crisis

Most people default to elbows. Elbows are fine. They’re classic. But if you want to elevate your french onion macaroni and cheese, look for Cavatappi or Campanelle. Cavatappi, those double-curve corkscrews with ridges, have more surface area. More surface area means more places for that onion-heavy cheese sauce to cling.

You must undercook the pasta. Seriously. If the box says 10 minutes for al dente, cook it for 7. It’s going to continue cooking in the oven as it absorbs the moisture from the sauce. If you start with soft pasta, you’ll end up with a tray of nursery food.

The Crucial Role of Beef Stock

Traditional French Onion Soup relies on a rich, dark beef consommé. To bridge that gap in a macaroni dish, some chefs, like J. Kenji López-Alt, have experimented with adding highly concentrated beef stock or even a dash of Worcestershire sauce to the onion mixture. It adds that "umami" punch that separates a generic cheese pasta from a true French onion tribute.

👉 See also: Weerts Funeral Home Davenport Iowa Obituaries: What Most People Get Wrong

I’ve found that reducing a cup of beef bone broth down to just two tablespoons and stirring that into the caramelized onions before mixing in the pasta adds a depth that salt alone cannot achieve. It mimics the richness of the soup's broth without thinning out your cheese sauce.

Breadcrumbs: To Toast or Not to Toast?

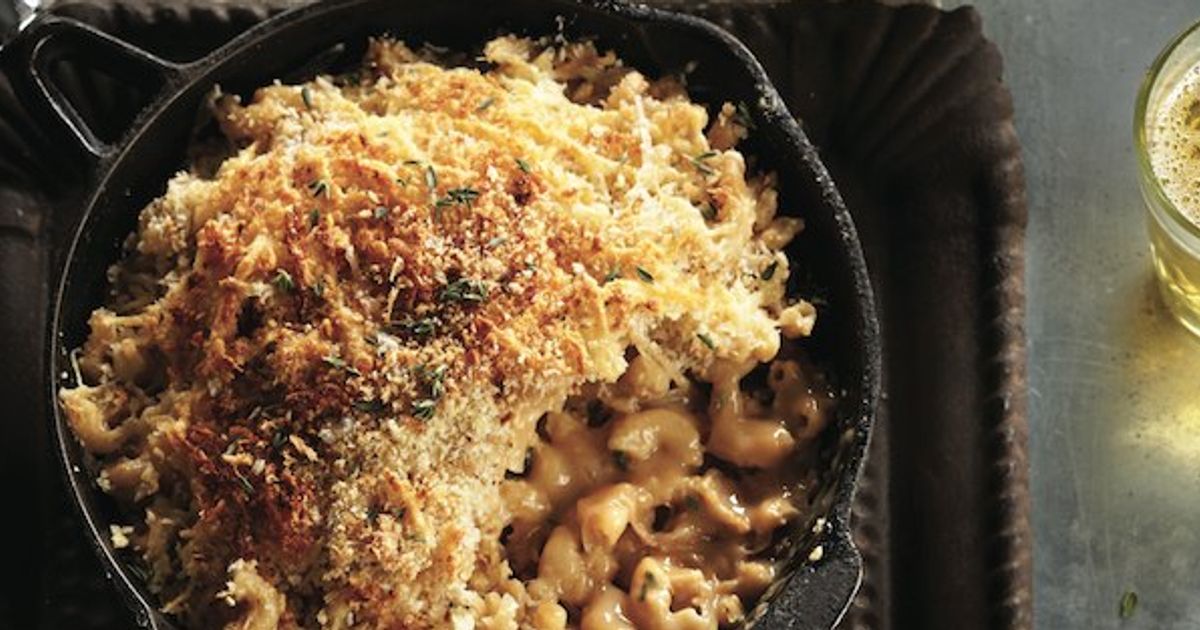

A lot of people throw plain Panko on top and call it a day. That’s a missed opportunity. To truly mimic the crostini on top of the soup, you should toss your breadcrumbs in melted butter, some fresh thyme, and maybe a little extra grated parmesan. Better yet? Use torn bits of a real sourdough baguette. The craggy edges get incredibly crispy under the broiler, providing the perfect textural contrast to the creamy interior.

Common Mistakes and How to Pivot

If you realize your onions are burning, don't just keep going. The bitterness will permeate the entire batch. Take the pan off the heat, add a tablespoon of water, and scrape the burnt bits away. If it’s too far gone, start over. Onions are cheap; your time and the cost of Gruyère are not.

If the sauce looks like it’s curdling as you add the cheese, it’s likely too hot. Remove the pot from the burner. Add a splash of cold milk and whisk like your life depends on it. Usually, you can bring an emulsion back from the brink if you catch it early enough.

The Final Assembly

When you’re ready to bake your french onion macaroni and cheese, don’t just dump it in a glass 9x13 dish and walk away. Layer it. Put half the mac in, then a layer of extra Gruyère, then the rest of the mac. This creates "cheese pockets" that stay gooey even after the top has crusted over.

✨ Don't miss: Getting Into Yale University: What the Admissions Office Is Actually Looking For

Bake it at 375°F. You want high enough heat to bubble the edges but not so high that you break the sauce. Finish it under the broiler for exactly sixty seconds. Watch it. Don't check your phone. The transition from "perfectly golden" to "charcoal" happens in the blink of an eye.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Batch

To get the most out of this recipe, you have to treat the onions as the main event, not a garnish.

- Slow-cook the onions for at least 40 minutes using a combination of butter and oil (the oil prevents the butter from burning too quickly).

- Deglaze with Sherry, making sure to scrape up every bit of the brown fond from the bottom of the pan.

- Grate your own cheese from a block to ensure a silkier sauce without the gritty additives found in pre-shredded bags.

- Use a blend of cheeses, specifically Gruyère for meltability and Sharp White Cheddar for flavor.

- Under-boil your pasta by at least 3 minutes compared to the package instructions to account for oven time.

- Incorporate umami by adding a splash of Worcestershire or a beef stock reduction to the onions.

- Top with buttered sourdough crumbs or even toasted baguette slices to replicate the classic soup experience.

Experimenting with different ratios of Gruyère to Cheddar can change the profile significantly. Some prefer a 70/30 split favoring the Gruyère for that authentic French taste, while others find a 50/50 split provides a more balanced "American comfort" feel. Either way, the slow-cooked onions remain the non-negotiable heart of the dish.