Think about a citrus fruit. If you peel an orange, you're basically taking the 2D "skin" of a 3D object and trying to flatten it out on a table. It's messy. It never lays perfectly flat because spheres are stubborn. This brings us to the formula surface area of a sphere, a piece of mathematical magic that explains exactly how much "skin" any perfect ball has, from a marble to the planet Jupiter.

The formula is $A = 4\pi r^2$.

It looks simple. Maybe too simple?

Most people just memorize it for a test and forget it by Tuesday. But if you're an engineer designing a pressurized fuel tank or a climate scientist calculating how much solar radiation hits the Earth, this isn't just a homework problem. It's a life-or-death calculation. Honestly, it’s one of those weirdly perfect parts of the universe where the math just clicks into place.

Why Does the Formula Surface Area of a Sphere Even Exist?

Archimedes. That's the guy you need to know. Back in ancient Greece, around 250 BCE, Archimedes was obsessed with spheres and cylinders. He actually considered his discovery of the sphere's surface area to be his greatest achievement. He even wanted it carved onto his tombstone.

The core realization he had was that the surface area of a sphere is exactly four times the area of its "shadow"—the flat circle you’d see if you sliced it right down the middle. If the area of a flat circle is $\pi r^2$, then the sphere wrapping around it is $4\pi r^2$.

It's strange, right? You’d think a curved, 3D shape would be more complicated than a clean multiplier of four. But it isn't. If you took a cylinder that perfectly "hugs" a sphere (same height, same width), the surface area of the sphere is exactly equal to the lateral surface area of that cylinder. This is called the Archimedes' Hat-Box Theorem. It’s the reason why map makers struggle so much—you can’t flatten a sphere onto a plane without stretching things, but the math tells us the total amount of "stuff" on the surface remains a constant.

Breaking Down the Variables

In $A = 4\pi r^2$, we only have one real variable: $r$.

🔗 Read more: How Fast Do Fighter Jets Fly: What Most People Get Wrong

- r (Radius): This is the distance from the very center of the sphere to any point on its edge. If you double the radius, you don't just double the surface area. You quadruple it. That's because the $r$ is squared.

- $\pi$ (Pi): Roughly 3.14159. It’s the ratio that defines everything circular.

- 4: The magic constant.

Imagine you're painting a small ball with a 1-inch radius. If you switch to a ball with a 2-inch radius, you’re going to need four times as much paint. This "square-cube law" quirk is why small animals lose heat faster than big ones—they have more surface area relative to their volume.

Real-World Math: Beyond the Textbook

You’ve probably used this formula without knowing it.

Take the aerospace industry. When NASA engineers design a heat shield for a capsule re-entering the atmosphere, they use the formula surface area of a sphere to calculate exactly how much thermal protection material is needed. If they’re off by even a tiny fraction, the friction of the atmosphere would burn right through the "cool" spots.

Or look at biology. Human lungs aren't spheres, but we use spherical modeling to understand alveoli—the tiny air sacs where oxygen exchange happens. By maximizing surface area through millions of tiny quasi-spheres, our lungs can fit the surface area of a half a tennis court into a single chest cavity.

Then there's the tech side. In 3D rendering and gaming, like in engines used for Fortnite or Call of Duty, calculating how light hits a curved surface relies on these geometric fundamentals. Ray tracing literally calculates "hits" on a surface area. If the math wasn't precise, the lighting would look "off" or "uncanny."

👉 See also: Why 3D Printed Musical Instruments Are Actually Practical Now

Common Mistakes People Make

Most people mess up the diameter versus the radius. It sounds dumb, but in the heat of a calculation, it's the #1 error.

If a problem says "the sphere is 10cm wide," that 10 is the diameter ($d$). You have to cut it in half to get the radius ($r = 5$) before you plug it into the formula. If you use 10, your answer will be four times larger than it should be.

Another one? Forgetting the units. Surface area is always "squared." Whether it's square inches, square meters, or square miles, if you don't square the unit, the answer is technically meaningless in a physical space.

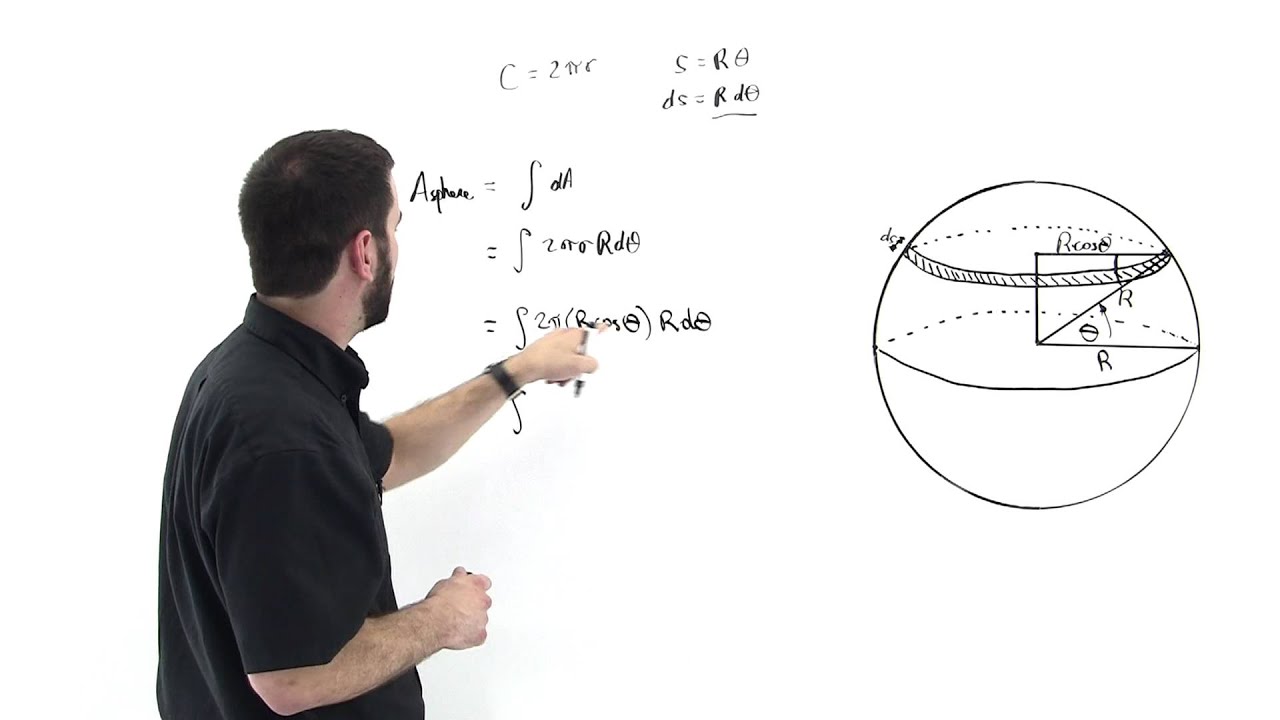

The Calculus Behind the Curtain

For the nerds out there (and I say that with love), you might wonder why it’s $4\pi r^2$. If you take the volume of a sphere, which is $V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$, and you take the derivative with respect to $r$, you get the surface area.

$$\frac{d}{dr}(\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3) = 4\pi r^2$$

This isn't a coincidence. It’s how calculus works. The surface area is essentially the "rate of change" of the volume as the radius grows. Think of it like adding infinite layers of an onion. Each layer you add is the surface area, and they all stack up to create the total volume.

Why This Matters for 2026 Technology

We are currently seeing a massive shift in spherical technology with the rise of "The Sphere" in Las Vegas and similar immersive venues. These structures use millions of LEDs. To calculate the pixel density and the total number of diodes required to cover that massive dome, engineers aren't just guessing. They are using the surface area of a hemisphere (half a sphere).

If you're building a "metaverse" or VR environment, the "skybox" is often a giant sphere surrounding the player. The resolution of the textures you need is directly tied to the surface area of that virtual sphere.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Spheres

If you’re working on a project—whether it's a DIY craft, a physics project, or a coding challenge—follow these steps to ensure your math holds up:

- Confirm your $r$: Measure the widest part of the object (diameter) and divide by 2. Do not trust your eyes; use a caliper if the object is small.

- Square the radius first: Before multiplying by $\pi$ or 4, square your radius. This is where most calculator errors happen.

- Check your environment: If you are dealing with a dome or a bowl, remember to divide your final result by 2. That's a hemisphere.

- Account for "waste": If you’re using the formula to buy material (like fabric or sheet metal), always add a 15-20% buffer. The formula gives you the perfect area, but real-world materials don't wrap without seams or overlaps.

Math is rarely as clean as a textbook makes it look. But with the sphere, we get as close to perfection as the universe allows. Next time you see a basketball or a planet, remember there’s a direct, 2,000-year-old link between its size and the space it occupies.

Next Steps

Start by measuring three spherical objects in your house—a marble, a grapefruit, and maybe a toy ball. Calculate their surface areas using the formula. You'll quickly see how a tiny increase in width leads to a massive jump in surface area. This hands-on "calibrating" of your brain will make the math intuitive rather than just a memorized line of text. For those moving into 3D design, practice "wrapping" a 2D texture map onto a sphere in Blender or Unity to see how the geometry translates into pixels.