If you’ve ever driven past the outskirts of Ypsilanti, Michigan, you might have noticed a massive, somewhat desolate expanse of concrete and steel. This is where the world changed. Honestly, the Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant is more than just an old factory; it’s basically the birthplace of the modern industrial age. It was a place where "impossible" became a daily quota.

Most people think Henry Ford just made cars, but during World War II, he and his son Edsel took on a challenge that literally terrified the U.S. government. They promised to build a B-24 Liberator bomber—a machine with over 300,000 parts—every single hour. The military didn't believe them. The press thought it was a publicity stunt. But the Fords weren't joking.

The Massive Scale of the Ford Motor Company Willow Run Plant

Willow Run was huge. Seriously. We’re talking about a facility that, at its peak, covered 5 million square feet. To put that in perspective, you could fit dozens of football fields inside and still have room for a small city. When it opened in 1941, it was the largest room in the world.

Constructing it was a nightmare. The ground was swampy, the timeline was non-existent, and the sheer logistics of moving thousands of workers in and out of a rural area every day was a mess. But Ford didn't care about the mud. He cared about the line. He applied the same assembly line philosophy that built the Model T to a four-engine bomber.

It worked.

By 1944, the Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant was hitting its stride. They weren't just building planes; they were manufacturing them like cheap toys. At the height of production, a completed B-24 rolled off the line every 63 minutes. Think about that for a second. A massive, lethal aircraft—ready to fly—every hour. It was insane.

📖 Related: Neiman Marcus in Manhattan New York: What Really Happened to the Hudson Yards Giant

Why the L-Shape?

There’s a funny bit of history about the plant's architecture. If you look at old aerial photos, the building has a distinct "L" shape. Why? Because Henry Ford didn't want to pay taxes to Washtenaw County. By curving the assembly line, he kept the majority of the production floor in Wayne County, where he had better political connections. It was a classic "old school" business move that complicated the actual manufacturing process just to save a few bucks.

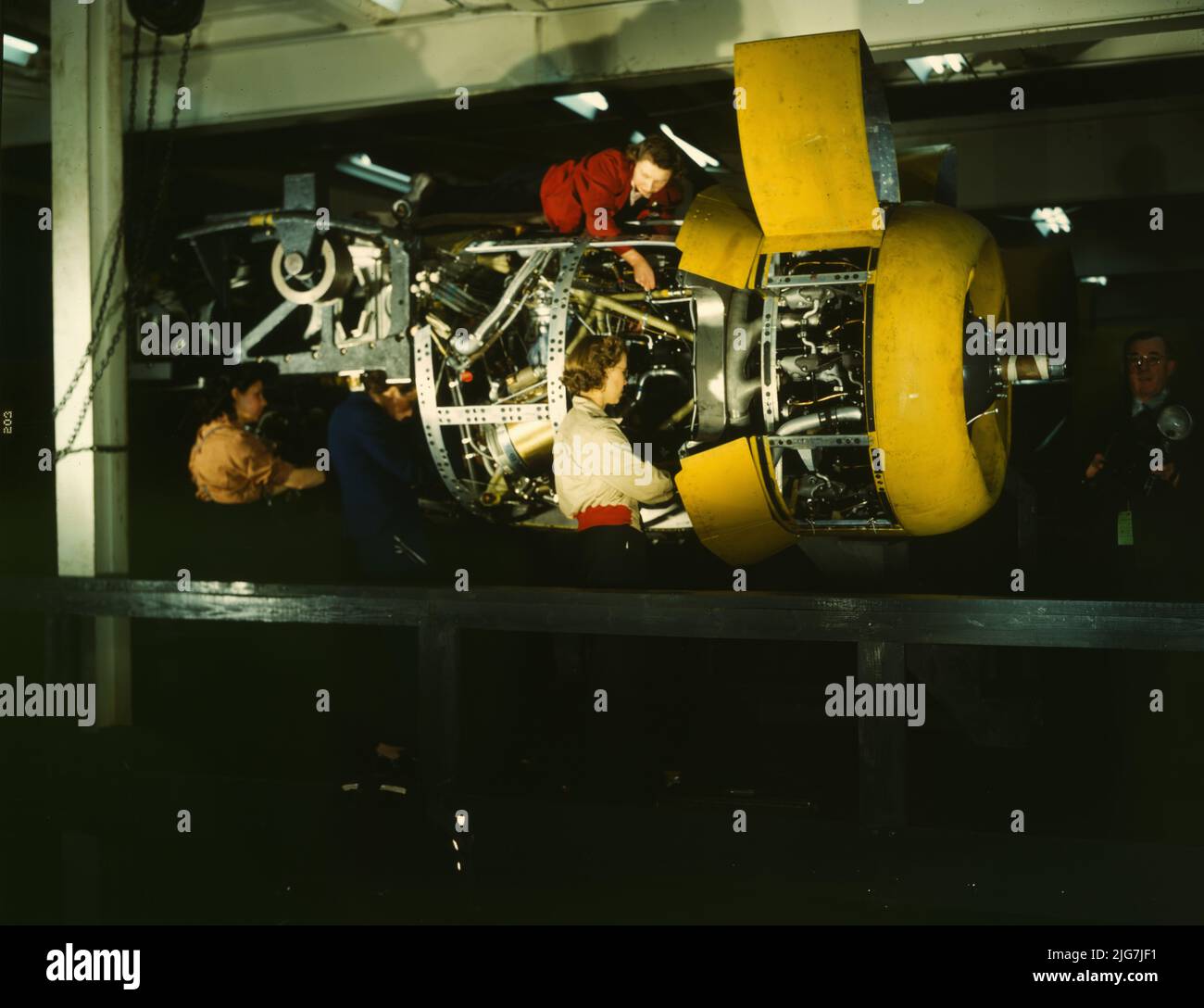

The "Rosie the Riveter" Connection

You’ve seen the poster. The "We Can Do It!" woman with the red bandana? That started here. While the character was a composite of many women, the real-life inspiration often pointed to Rose Will Monroe, who worked as a riveter at the Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant.

The workforce was a wild mix. Thousands of people migrated from the South—both Black and white families—looking for the high wages Ford promised. This created "Willow Village," a makeshift city of trailers and shacks that popped up overnight to house the 42,000 workers. It wasn't pretty. It was crowded, dirty, and tense. But it was the engine of the "Arsenal of Democracy."

The transition wasn't smooth. You had farmers who had never seen a wrench suddenly tasked with installing complex hydraulic systems. You had women entering the industrial workforce in numbers never seen before. It was a social revolution hidden inside a factory.

What Went Wrong After the War?

Once the war ended in 1945, the government didn't need thousands of bombers anymore. The Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant faced a massive identity crisis. Ford eventually walked away from the facility, and it went through a series of odd transitions.

👉 See also: Rough Tax Return Calculator: How to Estimate Your Refund Without Losing Your Mind

First, Kaiser-Frazer tried to make it a car plant. They had big dreams of taking on the Big Three, but they couldn't scale fast enough. Later, General Motors took over the site after their own transmission plant in Livonia burned down in 1953. GM used the space for decades, churning out Hydra-Matic transmissions and various parts for millions of Chevys and Buicks.

It’s kinda ironic, right? A plant built by Ford eventually became a backbone for his biggest rival.

The Modern Ghost and the Future of Mobility

By the time the 2008 financial crisis hit, the glory days of Willow Run were long gone. GM went through bankruptcy, and the plant was largely shuttered. For a few years, it looked like the whole place would be leveled and forgotten.

But then came the robots.

Today, a significant chunk of the old Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant site has been transformed into the American Center for Mobility (ACM). Instead of bombers, the site is now used to test self-driving cars and autonomous tech. The massive paved runways that once saw B-24s taking off for Europe are now proving grounds for AI-driven semis and electric SUVs.

✨ Don't miss: Replacement Walk In Cooler Doors: What Most People Get Wrong About Efficiency

It’s a strange full-circle moment. The place that mastered the mechanical assembly line is now trying to master the digital one.

The Yankee Air Museum

You can't talk about Willow Run without mentioning the Yankee Air Museum. After a devastating fire in 2004, the museum fought tooth and nail to save a portion of the original bomber plant. They eventually secured a piece of the building—the "folder" at the end of the assembly line where the planes exited. It’s a shrine to the people who worked there. If you ever visit, you can feel the ghosts of the 1940s. The smell of oil and old metal never really leaves a place like that.

Why Should We Care in 2026?

We live in an era of "just-in-time" manufacturing and global supply chains that feel incredibly fragile. Willow Run reminds us of what happens when a nation decides to actually build things at scale.

It wasn't perfect. The environmental impact was huge, the labor disputes were brutal, and the racial tensions in the housing projects were a precursor to the civil rights struggles of the following decades. But the sheer audacity of the Ford Motor Company Willow Run plant is something we rarely see today.

When people say "they don't make 'em like they used to," they are usually talking about the cars. But they should be talking about the factories.

Actionable Insights for History and Industry Buffs

If you're interested in the legacy of Willow Run or industrial history, here is how you can actually engage with it today:

- Visit the Yankee Air Museum: Located right on the site, it’s the best way to see the remaining structure. They often have fly-ins where you can actually see B-24s or B-17s in the air.

- Research the "Arsenal of Democracy" Archives: The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn holds the primary documents, including the original blueprints and labor records for the plant. It's a goldmine for researchers.

- Explore the American Center for Mobility: While it's a secure testing facility, they often hold industry events. If you’re in the tech or automotive sector, seeing how they’ve repurposed the old bomber runways for autonomous vehicle testing is fascinating.

- Track the "Rosie" Legacy: Look into the "Save the Bomber Plant" campaign records. It’s a great case study in how local communities can preserve massive industrial sites through grassroots fundraising.

The Willow Run story isn't over. It has transitioned from a swamp to a bomber factory, to a car plant, to a tech hub. It remains a testament to the fact that in American industry, the only constant is reinvention.