It’s one of the weirdest footnotes in military history. Most people hear the name "The Football War" and assume two countries lost their minds over a referee’s bad call. They didn't. Calling it the Honduras El Salvador war because of a soccer match is like saying a single matchstick caused a forest fire while ignoring the ten tons of dry timber and spilled gasoline sitting underneath it.

Soccer was just the spark.

In June 1969, El Salvador and Honduras played a three-game qualifying round for the 1970 World Cup. Tensions were already screaming high. By the time the third game ended in Mexico City, fans were rioting, diplomatic ties were severed, and within weeks, Salvadoran fighter jets were dropping bombs on Honduran soil. It lasted 100 hours. It killed thousands. And honestly, it had almost nothing to do with the sport of football and everything to do with land, immigration, and a massive failure of regional politics.

The Real Powder Keg: Land Reform and Migration

If you want to understand the Honduras El Salvador war, you have to look at a map and a census from the late 1960s. El Salvador is tiny. Even today, it’s the most densely populated country in Central America. Back then, it was dominated by a few wealthy landowning families—often called the "14 Families"—who owned almost everything. The rural poor had nowhere to go.

So they left.

By 1969, roughly 300,000 Salvadorans had crossed the border into Honduras. Most were "squatters" or sharecroppers. Honduras is much larger geographically, and at the time, it had a much smaller population. For decades, this was a safety valve for El Salvador. It kept the poor from revolting at home because they could just go find a plot of land in Honduras to farm.

Then things got messy.

Honduran President Oswaldo López Arellano was facing his own internal pressure. Local labor unions and the landed elite in Honduras weren't happy. They saw the Salvadoran immigrants as competition for land and resources. To save his own political skin, Arellano turned the Salvadorans into a convenient scapegoat. He passed a land reform law that didn't just redistribute land from the wealthy—it specifically took land away from Salvadoran immigrants, regardless of how long they had lived there or if they had legal claims.

💡 You might also like: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

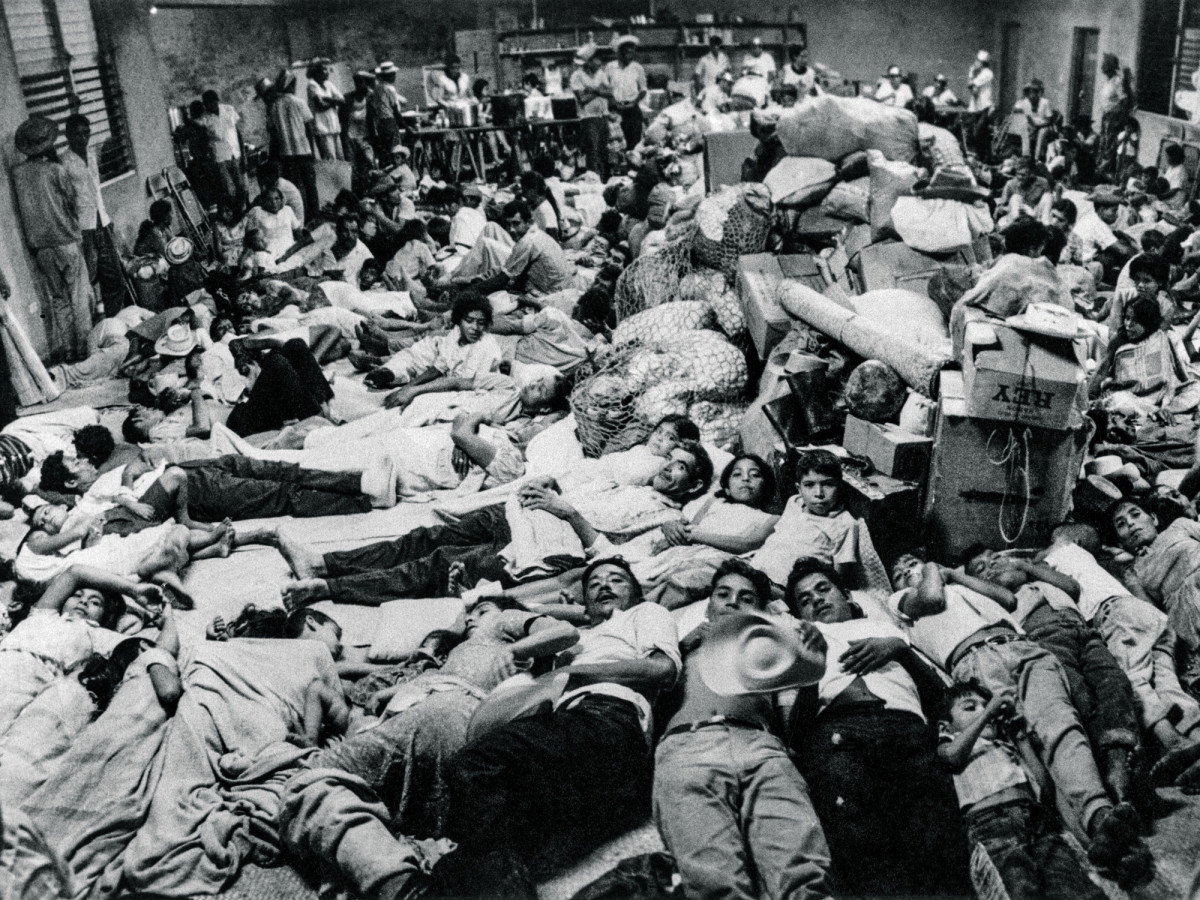

Expulsions began. Thousands of Salvadorans were harassed, beaten, or forced to flee back across the border into a country that didn't have room for them. The Salvadoran government, led by Fidel Sánchez Hernández, panicked. If 300,000 angry, landless peasants returned all at once, his government would likely collapse in a revolution.

When the Stadium Became a Battleground

This is where the soccer matches come in.

The first game happened in Tegucigalpa on June 8, 1969. Honduras won 1-0. A young Salvadoran woman named Amelia Bolaños reportedly shot herself in the heart because she couldn't bear the shame of the loss. She became a national martyr in El Salvador. When the Honduran team arrived in San Salvador for the second game a week later, the atmosphere was poisonous.

The Salvadoran fans didn't just boo. They stayed up all night outside the Honduran team's hotel, screaming, throwing rocks, and (according to some accounts) dumping dead rats near the players' windows. The Honduran players were terrified. Unsurprisingly, El Salvador won that game 3-0. The Honduran coach reportedly told his players they were lucky to leave the stadium alive.

By the third playoff game in Mexico City on June 27, the two countries had already broken off diplomatic relations. El Salvador won 3-2 in extra time. But the victory on the pitch was overshadowed by the violence in the streets.

The Honduras El Salvador war was now inevitable.

100 Hours of Chaos

On July 14, 1969, the Salvadoran Air Force launched a surprise attack. Their goal was to knock out the Honduran Air Force on the ground and seize enough territory to force a favorable treaty regarding the migrants.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

It was a strange, "vintage" war. Because both countries were relatively poor and relied on older American equipment, the sky was filled with P-51 Mustangs and F4U Corsairs. These were World War II-era propeller planes fighting each other decades after they had been retired by major powers. It’s actually the last time in history that piston-engine fighters engaged in a dogfight.

The Salvadoran army moved fast. They pushed along the main roads, capturing several Honduran towns. But they hit a massive problem: logistics. They ran out of fuel and ammunition almost immediately.

Meanwhile, the Honduran Air Force wasn't totally destroyed. They fought back, bombing Salvadoran oil facilities and ports. This crippled the Salvadoran advance. While El Salvador had the better ground army, Honduras controlled the skies.

The Organization of American States (OAS) stepped in fast. They didn't want a full-scale regional collapse. They threatened El Salvador with heavy sanctions if they didn't pull back. By July 18, a ceasefire was signed. The actual shooting lasted just over four days, which is why it's often called the "100 Hour War."

The Brutal Aftermath Most People Ignore

The war ended quickly, but the tragedy was just starting. Roughly 2,000 to 3,000 people were dead, most of them Honduran civilians.

But the real "win" for Honduras and the "loss" for El Salvador came after the guns stopped firing. El Salvador was forced to withdraw its troops, but they couldn't stop the flow of refugees. Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans were forced out of Honduras. They returned to a country that was small, overpopulated, and now economically shattered.

This pressure cooker directly led to the Salvadoran Civil War a decade later. The social tensions that the soccer war failed to solve eventually boiled over into a much longer, much bloodier conflict that lasted from 1979 to 1992.

👉 See also: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

Also, the Central American Common Market (CACM), which was supposed to integrate the region's economies, was basically destroyed. It took 22 years for the two countries to finally sign a peace treaty that settled the border dispute in 1992, following a ruling by the International Court of Justice.

What This Teaches Us About Modern Conflict

The Honduras El Salvador war is a case study in how domestic problems—like land inequality—are often "exported" through nationalism. Leaders in both countries used the soccer matches to whip up patriotic fervor to distract people from the fact that their governments were failing them.

It’s easy to blame the fans in the stadium. It’s harder to look at the decades of failed land policy and corporate influence (like the United Fruit Company, which held massive amounts of land in Honduras) that created the tension in the first place.

Key Takeaways for History Buffs

- Don't trust the name. Soccer was the catalyst, but land reform and migration were the causes.

- Logistics win wars. El Salvador's superior infantry couldn't hold ground because they lacked a steady supply of fuel.

- Propeller power. This was the final sunset for WWII-era aircraft in active combat roles.

- Long-term trauma. The war caused the collapse of regional trade and set the stage for one of the bloodiest civil wars in the Americas.

How to Dig Deeper into This History

If you're genuinely interested in the nuances of this conflict, skip the sensationalist YouTube clips and look at the primary sources.

- Read Ryszard Kapuściński. He was a Polish journalist who was actually there. His book, The Soccer War, is legendary. Just be aware that he’s known for a "literary" style that sometimes blurs the line between hard fact and atmospheric storytelling.

- Check the ICJ Archives. If you want to see how the border was finally settled, the International Court of Justice records from 1992 provide the most detailed maps and historical land claims available.

- Study the 1970s Salvadoran Economy. To see why the war was so devastating, look at El Salvador's GDP and population density metrics following the 1969 return of refugees. It explains the lead-up to the 1979 civil war better than any political manifesto.

The border between these two nations is peaceful today, but the scars of 1969 still influence how migration is handled in Central America. Understanding this conflict isn't just about trivia; it's about seeing how quickly a sports rivalry can be weaponized by politicians who have no other way to stay in power.

Actionable Insight: If you are researching Central American history, always look for the "safety valve" theory. In this region, migration has historically functioned as a way to avoid internal revolution. When that valve is closed—as it was during the 1969 war—internal conflict is almost guaranteed to follow. Use this lens to analyze modern migration patterns in the Northern Triangle for a more sophisticated understanding of current events.