Everything felt impossibly heavy and incredibly light all at once on July 20, 1969. While the world watched a grainy, flickering black-and-white broadcast, two men were actually living through the most high-stakes engineering experiment in human history. We talk about the first walk on the moon like it was a cinematic masterpiece, but the reality was a lot gritier, smellier, and more precarious than the history books usually let on. It wasn't just about "one small step." It was about a descent that almost ended in a crash, a door that was hard to open, and a pervasive smell of spent gunpowder that followed the astronauts back into the lunar module.

Most people think the landing was a breeze. It wasn't. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were hurtling toward the surface of the Moon in the Eagle while their computer was screaming "1202" and "1201" alarms at them. Basically, the tech was overloaded. It couldn't handle the data. Armstrong had to take manual control because the autopilot was steering them right into a boulder-strewn crater the size of a football field. He hovered, burning through precious fuel, until they finally touched down with maybe 30 seconds of "bingo fuel" remaining. If he’d waited any longer, they’d have had to abort or, well, they wouldn't have come home.

The First Walk on the Moon and the Tech That Almost Failed

When we look back at the first walk on the moon, we often forget how primitive the technology was compared to the phone in your pocket. The Apollo Guidance Computer had about 74 kilobytes of memory. That’s it. For perspective, a single low-res photo today is bigger than the entire brain of the ship that went to the lunar surface.

The hatch was another story. It was designed to stay sealed tight against the vacuum of space, obviously. But once they depressurized the cabin to step outside, the residual pressure made the door incredibly stubborn. There’s this brief moment of tension where they had to be careful not to break the handle. Imagine being 238,000 miles from home and the door gets stuck.

Why the "Small Step" Took So Long

It took hours to actually get out of the lunar module. People think they landed and just hopped out. Nope. They had to eat a meal, go through a massive checklist, and then struggle into those bulky suits. The suits themselves were pressurized like stiff balloons. Moving your fingers felt like squeezing a tennis ball over and over again. By the time Armstrong actually climbed down that ladder, his heart rate was spiking. He wasn't just nervous; he was physically exhausted.

When he finally hit the lunar dust, he didn't just walk. He tested the soil. He was worried they might sink into it like quicksand, a theory some scientists had floated before the mission. But the dust was firm. It felt like fine talcum powder but smelled—strangely—like burnt charcoal or spent gunpowder. That’s a detail Aldrin noted once they got back inside and took their helmets off. The Moon has a scent.

The Logistics of Standing on Another World

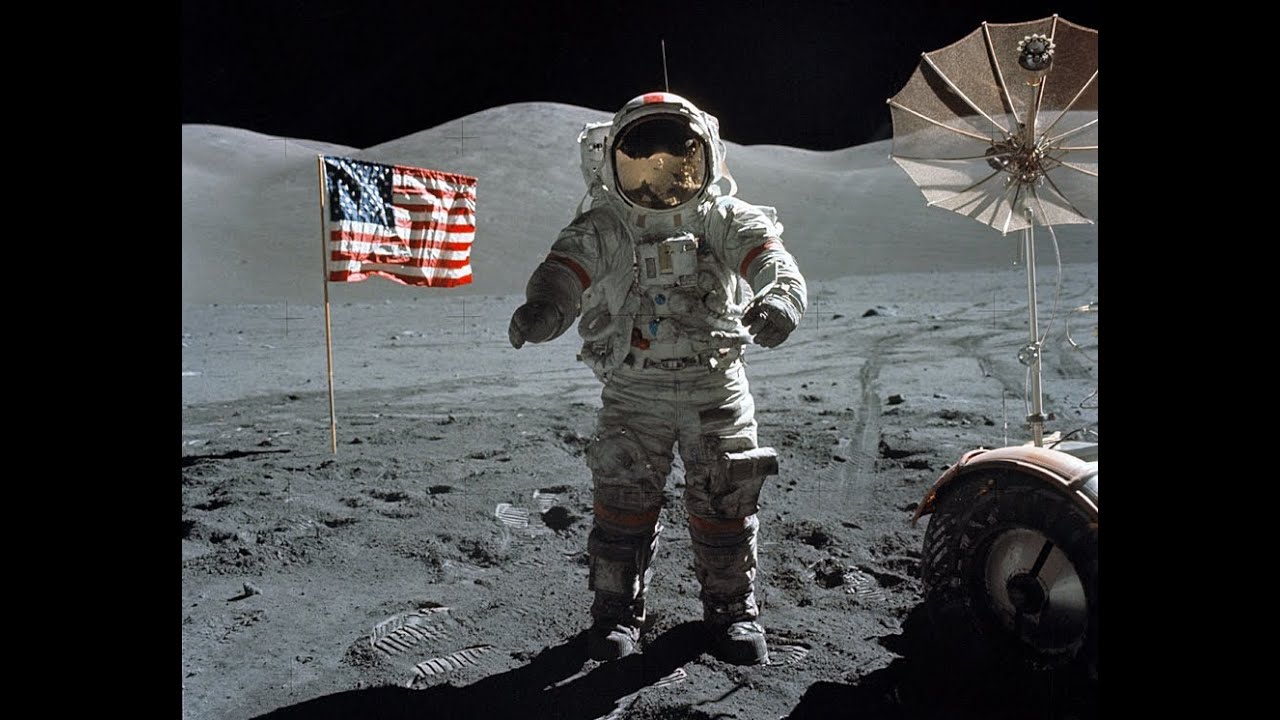

Walking on the Moon isn't like walking on Earth. Obviously. Gravity is only one-sixth of what we’re used to. Armstrong and Aldrin had to learn how to move all over again. If you try to walk normally, you end up tripping because your legs move faster than your body weight expects. They developed this "kangaroo hop" because it was the most efficient way to get around without falling flat on their faces.

Honestly, the sheer amount of gear they left behind is staggering. We see the flag and the footprints, but the first walk on the moon also involved dumping a bunch of "jettison bags" filled with trash and human waste. They had to shed weight to make sure the ascent engine could get them back up to Michael Collins in the Command Module Columbia.

- The Lunar Laser Ranging Retroreflector (still used today to measure the distance to the Moon).

- The Seismic Experiment Package (to listen for moonquakes).

- A gold olive branch (a symbol of peace).

- Silicon disc with messages from 73 world leaders.

Misconceptions and the Cold Hard Facts

One big thing people get wrong: the flag didn't "wave" because of wind. There is no wind on the Moon. It waved because it was held up by a horizontal telescopic crossbar that didn't fully extend. The "ripples" were just folds in the fabric that stayed that way because of the low gravity. NASA actually struggled with that flag more than they expected. The lunar soil was surprisingly tough just a few inches down, making it hard to plant the pole.

Then there’s Michael Collins. While the first walk on the moon was happening, he was the loneliest man in history. Every time his orbit took him behind the Moon, he lost all radio contact with Earth. He was in total silence, 60 miles above his friends, wondering if he’d have to go home alone if their engine failed to ignite. He later wrote that he felt a "sweaty concern" but never felt lonely, just intensely focused.

The Problem with the Dust

Lunar dust—regolith—is nasty stuff. It’s not like beach sand. On Earth, wind and water wear down rock particles until they’re round. On the Moon, there’s no erosion. The dust is jagged, like tiny shards of glass. It clogged the seals on the space suits and scratched the visors. During that very first walk, the astronauts realized quickly that the Moon was a hostile environment that wanted to tear their equipment apart.

💡 You might also like: Why Red Black Gradient 8k is the Only Wallpaper Your High-End Monitor Needs

The Science We Gained

We didn't just go there to win a race with the Soviets. The samples brought back during the first walk on the moon—about 47 pounds of rock and soil—changed everything we knew about the solar system. Before Apollo 11, we weren't sure how the Moon formed. The "Giant Impact" theory, which suggests a Mars-sized object slammed into Earth and the debris formed the Moon, gained massive traction because the chemical signatures in those rocks were so similar to Earth's mantle.

It wasn't just "rocks." It was a time capsule. Because the Moon has no atmosphere and no plate tectonics, its surface hasn't changed in billions of years. Walking on the Moon was like walking on the early history of our own planet.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you're fascinated by this, don't just take a textbook's word for it. The data is out there.

- Check the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) imagery. You can literally see the landing sites from high-resolution satellite photos taken recently. The descent stage of the Eagle is still there. The tracks from the astronauts’ boots are still visible because there’s no wind to blow them away.

- Listen to the Apollo 11 Flight Journal. NASA has transcribed and uploaded the entire audio of the mission. It’s not all "heroic" talk. A lot of it is technical jargon, some of it is joking, and some of it is just the sound of men trying to stay alive in a vacuum.

- Visit the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Seeing the Columbia command module in person puts the scale into perspective. It is incredibly small. You realize that three men lived in a space roughly the size of a large car for eight days.

The first walk on the moon wasn't a singular event; it was the culmination of 400,000 people working together on the Apollo program. It was a feat of raw human will and math. We didn't have the computers to do the heavy lifting, so we did it with slide rules and grit.

The next time you look at the Moon, remember that for a few hours in 1969, it was a workplace. It was a place where two guys did chores, took photos, and worried about their fuel levels. It wasn't a myth. It was an engineering miracle.

To truly understand the gravity of that moment, look into the "Contingency Speech" written for President Nixon in case Armstrong and Aldrin couldn't leave the surface. It’s titled "In Event of Moon Disaster." Reading it makes you realize just how close we were to a very different kind of history. Study the lunar samples' chemical compositions if you want the hard science, or watch the restored 4K footage of the EVA (Extravehicular Activity) to see the "kangaroo hop" in action. The history is vibrant, messy, and far more interesting than the simplified version we learned in school.