It was grainy. It was blurry. Honestly, if you saw it today without context, you’d probably think it was a smudge on an old film reel or a poorly photocopied Rorschach test. But that smeary, black-and-white blob captured on August 14, 1959, changed everything about how we see our home.

We’re talking about the first satellite picture of earth.

Before the high-definition "Blue Marble" shots or the real-time satellite feeds we scroll through on our phones, there was Explorer 6. It wasn't a sleek, silver orb like you see in modern sci-fi. It looked more like a giant paddleball with solar cells sticking out at awkward angles. This clunky piece of 1950s tech managed to do something humans had dreamt of since the dawn of time: it looked back.

It’s easy to forget that for most of human history, "Earth" was just the ground under our boots. We knew it was round, sure, but we’d never actually seen it as a distinct object floating in the void.

Why Explorer 6 Was a Total Game Changer

The first satellite picture of earth wasn't just a PR stunt for NASA. You have to remember the context of 1959. The Cold War was freezing cold. The Space Race was basically a sprint to see who could get the high ground first. When Explorer 6 launched from Cape Canaveral, its mission was actually to study the Van Allen radiation belts and the Earth's magnetic field. The camera—a crude scanning device—was almost an afterthought.

Actually, calling it a "camera" is being generous.

It was a small television-like scanner. As the satellite spun, the scanner built up an image line by line. It took about 40 minutes to transmit a single frame back to a station in Hawaii. Think about that for a second. We get frustrated when a 4K video takes three seconds to buffer. These engineers waited nearly an hour for a bunch of electronic pulses to tell them if they’d caught a glimpse of the Pacific Ocean.

The resulting image showed a sun-lit area of the Central Pacific Ocean and its cloud cover. It was taken from about 17,000 miles up. It wasn't "pretty" by any stretch of the imagination, but it proved the concept. We could observe weather patterns from above. We could see the curve. We were no longer stuck looking up; we were finally looking down.

🔗 Read more: The Truth About How to Get Into Private TikToks Without Getting Banned

The Messy Reality of Early Space Photography

There’s a common misconception that once we got into orbit, the pictures were instantly amazing. Nope. Not even close.

The first satellite picture of earth was basically a miracle of data reconstruction. The signal was weak. The "noise" from cosmic radiation was everywhere. When the data arrived at the ground station, it was just a string of numbers. Scientists had to manually translate those numbers into shades of gray to "see" the image.

It's sorta like trying to paint a portrait by having someone yell hex codes at you over a static-filled radio.

- Explorer 6 (1959): The pioneer. Crude, blurry, but historic.

- TIROS-1 (1960): The first dedicated weather satellite. This is when the images started actually looking like "land" and "sea."

- ATS-3 (1967): The first full-color high-res image of the entire Earth disk.

- Apollo 8 (1968): "Earthrise." This wasn't a satellite, but a human with a Hasselblad, yet it owes its existence to the path blazed by Explorer 6.

If you look at the Explorer 6 image today, you can barely make out the clouds. In fact, many people at the time were underwhelmed. They expected a postcard. What they got was a grainy mess that required a PhD to interpret. But for the scientific community, it was the "Proof of Concept" that birthed modern meteorology.

Debunking the V-2 Rocket Myth

A lot of people get confused and think the first satellite picture of earth came from a V-2 rocket in 1946. It’s a fair mistake, but technically wrong.

After World War II, American scientists used captured German V-2 rockets to carry cameras into suborbital space. On October 24, 1946, a 35mm motion picture camera captured frames from an altitude of 65 miles. While these are technically the first photos of Earth from space, they weren't satellite pictures.

Why does that distinction matter?

💡 You might also like: Why Doppler 12 Weather Radar Is Still the Backbone of Local Storm Tracking

A rocket goes up and comes back down. It’s a snapshot in time. A satellite stays there. It orbits. It provides a continuous, systematic view of the planet. Explorer 6 was the first time we stayed in the "balcony seat" of the universe to watch the show below. That's a massive leap in technological complexity.

The V-2 photos showed us the curve; the Explorer 6 satellite picture showed us the system.

The Tech Behind the Blur

How did they actually do it? No SD cards. No digital sensors as we know them.

The imaging system on Explorer 6 used a single photo-unit. Because the satellite was spinning, the "camera" would catch a tiny sliver of the Earth with every rotation. It was a scanning process. Imagine trying to take a photo of a moving car by looking through a straw and moving your head up and down.

The data was converted into an analog signal, beamed across thousands of miles of empty space, and recorded on magnetic tape. The "dots" (pixels) were then printed out. It was incredibly lo-fi.

But it worked.

Interestingly, the satellite only lasted a few months. It was plagued by power issues—only three of its four solar paddles deployed correctly. Despite the mechanical failures and the low-resolution output, the first satellite picture of earth remains a cornerstone of the space age.

📖 Related: The Portable Monitor Extender for Laptop: Why Most People Choose the Wrong One

How to View These Images Today

If you’re a space nerd, you don't have to take my word for it. NASA maintains an incredible archive of these early missions. You can actually find the original press release from 1959 which describes the image as showing "a sun-light area of the Central Pacific Ocean."

Checking out the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum is also a solid move. They have exhibits that show the scale of these early "paddlewheel" satellites. Seeing the hardware in person makes you realize how gutsy those early engineers were. They were basically launching "smart" tin cans into a vacuum and hoping the math was right.

Surprising Facts Most People Miss

- The Hawaii Connection: The data for the first photo was received at a station in South Point, Hawaii.

- The "Crude" Scanner: The resolution was so low that if a city were in the shot, you wouldn't have seen it. You could only see massive cloud systems.

- Orbit Issues: Explorer 6 was in a very elliptical orbit, which made consistent imaging almost impossible.

- The "Paddlewheel" Nickname: The satellite was nicknamed "Paddlewheel" because of those solar panels, which were a brand-new technology at the time.

Why We Still Care

It’s about perspective.

Before the first satellite picture of earth, our maps were drawings based on surveys and guesswork. We had no idea what a hurricane looked like from the top. We didn't know how interconnected the atmosphere really was. That grainy image was the "Hello World" of environmental science.

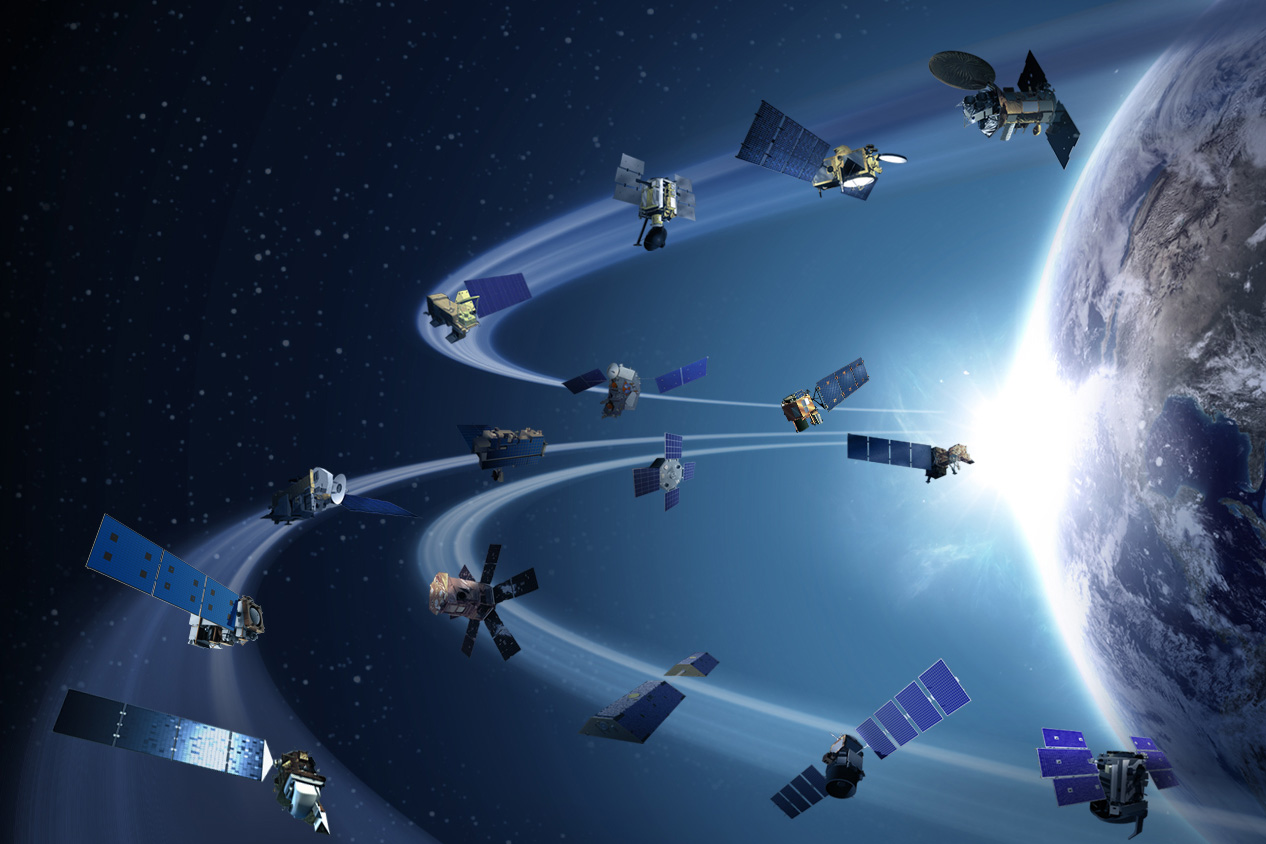

Today, we have satellites like DSCOVR, which sits a million miles away at the L1 Lagrange point, taking constant, high-resolution color photos of the entire sunlit side of the Earth. We have the GOES satellites that track every lightning strike and cloud shift in real-time.

But all of that—every bit of it—leads back to that one fuzzy, gray, 1959 snapshot. It was the moment the Earth finally looked in the mirror.

Actionable Insights for the Space Enthusiast

If you want to dive deeper into the history of orbital imaging, don't just look at the photos. Follow these steps to get the full technical picture:

- Search the NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS): Look for the "Explorer VI Final Report." It contains the actual signal charts and the engineering headaches involved in getting that first image.

- Compare the V-2 vs. Explorer 6: Look at the 1946 suborbital shots side-by-side with the 1959 satellite shot. Notice the difference in "horizon dip" and how much more of the Earth is visible from the satellite's higher altitude.

- Explore "Earth Observation" History: Research the TIROS program if you want to see how we went from "one-off photo" to "daily weather reports." It’s the direct descendant of the Explorer 6 experiment.

- Check out the "Blue Marble" 1972 photo: Contrast it with the 1959 image. It shows just how far imaging technology (and human presence in space) advanced in just thirteen years.

The transition from a grainy blob to a vibrant blue planet wasn't just about better cameras; it was about the maturation of our species as a spacefaring civilization. That first photo was the first step out the door.