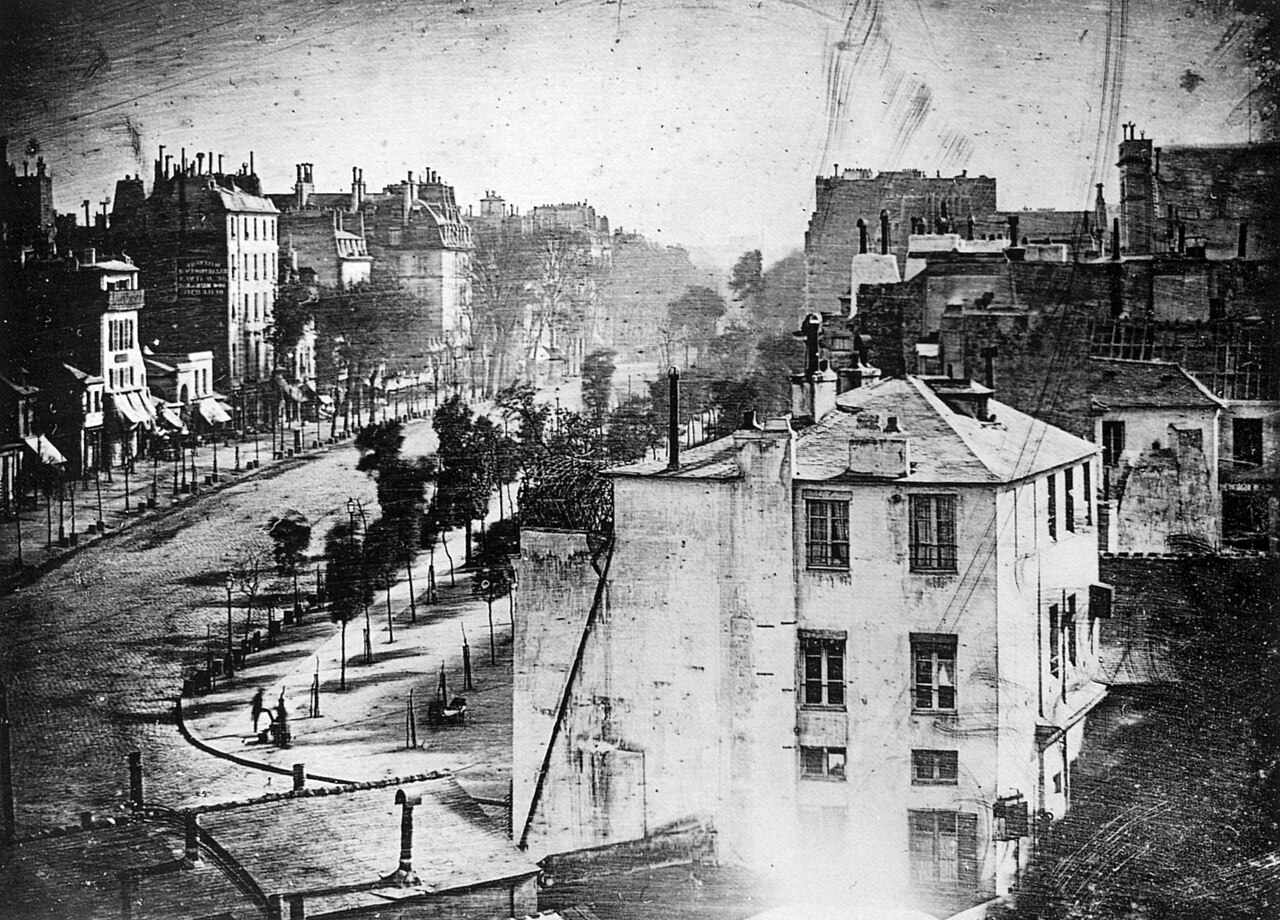

Look closely. You’ve probably seen the image before without realizing what you were actually looking at. It's a hazy, silver-plated view of a Parisian street from 1838. At first glance, the Boulevard du Temple looks deserted. Empty. Like a ghost town. But in the bottom-left corner, there’s a guy getting his boots shined.

That’s it. That is the first photograph of a human.

It wasn't a posed portrait. It wasn't a family photo. It was a complete accident. Louis Daguerre, the man who basically birthed modern photography, wasn't even trying to capture a person. He was just trying to prove his "daguerreotype" process worked. Because the exposure time was so incredibly long—we’re talking ten minutes or more—anything moving simply vanished. The carriages, the horses, the hundreds of people walking by? Gone. They were moving too fast for the chemicals to register them. But this one guy? He stayed still long enough to be etched into history forever.

He was just getting his shoes polished.

The Chemistry of a Ghost Town

To understand why this photo is so weird, you have to understand how difficult it was to take a picture back then. This wasn't a "point and shoot" situation. Daguerre was using a silver-plated copper sheet sensitized with iodine vapor.

The Boulevard du Temple was one of the busiest streets in Paris. It was nicknamed "Boulevard du Crime" because of all the theaters showing melodramas. It should have been packed. But the 1838 technology had a massive limitation: the "slow" shutter speed. It wasn't actually a shutter; it was just Daguerre removing a lens cap.

💡 You might also like: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

If you walk across a room while a camera is taking a ten-minute exposure, the camera doesn't see you. You're a blur that eventually averages out into the background. The only reason we see the first photograph of a human here is because that anonymous man stood perfectly still. He had his foot up on the bootblack’s stand. The bootblack was also moving, which is why he looks a bit more like a blurry smudge than the customer, but both are clearly there.

Who were they?

We will never know. That’s the haunting part. Two people, living their lives in 1838 Paris, had no idea they were becoming the first humans ever recorded by light and chemistry. Some historians, like Beaumont Newhall, have spent years squinting at the plates. If you look even closer at high-resolution scans from the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, you might see a few other ghosts. There's a faint outline of a person sitting on a bench. Maybe a child looking out a window. But the boot-shine man is the only one who is truly "there."

Why the First Photograph of a Human Changed Everything

Before this moment, if you wanted to see a human face, you needed a painter. Painting is subjective. A painter can make you look younger, thinner, or more heroic. Photography promised something different: "The Pencil of Nature." That’s what William Henry Fox Talbot called it.

When Louis Daguerre showed this plate to the French Academy of Sciences in 1839, people were legitimately terrified. They’d never seen detail like this. You could see the textures of the stone. You could see the distance. And then, there was that tiny, solitary figure.

It shifted the human psyche. Suddenly, time could be frozen.

📖 Related: Finding the 24/7 apple support number: What You Need to Know Before Calling

- It wasn't just art anymore.

- It was evidence.

- It was a footprint in time.

Honestly, the daguerreotype was a bit of a nightmare to handle. The image is on a mirror-like surface. To see it, you have to tilt it just right, or you just see your own reflection. It's meta. You’re looking at the first human in a photo while looking at yourself.

Misconceptions About Daguerre’s Masterpiece

A lot of people think the first photograph of a human was a "selfie." Nope. Robert Cornelius took the first intentional photographic self-portrait in 1839, a year later, in Philadelphia. He had to run into the frame and sit still for a minute.

Another mistake? People think this was the first photo ever. It wasn't. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the "View from the Window at Le Gras" in 1826 or 1827. But that photo took eight hours to expose. No human is going to stand still for eight hours. Niépce’s photo looks like a grainy mess of rooftops. Daguerre’s photo was the first to capture the "decisive moment," even if that moment lasted ten minutes.

There's also a theory that the boot-shiner was a plant. Some skeptics think Daguerre hired the guy to stand there so he could prove his camera could capture people. While it's possible, most historians think it was just a lucky break. The placement is too natural, too tucked away in the corner.

The Technical Nightmare of 1838

If you tried to recreate this today, you'd realize how much of a genius—or a madman—Daguerre was.

👉 See also: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

- You had to polish the silver plate until it was a literal mirror. Any scratch would ruin the shot.

- You had to use mercury vapor to "develop" the image. Yes, mercury. It’s incredibly toxic.

- You had to "fix" the image with salt water (later hyposulfite of soda) so it wouldn't turn black when it hit the sun.

The Boulevard du Temple plate is actually a mirror image of reality. Because of the way the lens worked without a prism, everything is flipped. The guy getting his boots shined was actually on the other side of the street.

How to View This History Today

If you want to see the real thing, it's tough. The original 1838 plate is kept in a museum in Munich (the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum). It’s incredibly fragile. Light kills it. Most of what you see online is a high-quality reproduction made from a 19th-century copy.

Looking at it teaches us about patience. In 2026, we take 50 photos of our lunch in ten seconds. Daguerre waited ten minutes for one frame. The first photograph of a human reminds us that the world is moving fast, and sometimes, the only way to be remembered is to just stop and stay still for a second.

It’s kind of poetic. The most famous man in early photography is a guy whose name we don't know, who was just trying to get his shoes cleaned before going about his day. He's a ghost in the machine.

Actionable Insights for History and Photo Buffs

If you're fascinated by this era of technology, don't just look at the JPEGs.

- Visit a local archive: Many university libraries have original daguerreotypes. Seeing one in person is a completely different experience; the depth is almost 3D because of the silver.

- Try "Slow Photography": Use a neutral density (ND) filter on a modern camera to take a 5-minute exposure of a busy street. You'll see exactly what Daguerre saw—a "ghost city" where only the stationary objects remain.

- Research the "View from the Window at Le Gras": If you want to see the absolute beginning, look up Niépce’s work. It’s the raw, ugly ancestor of the Daguerreotype.

- Study the Robert Cornelius Self-Portrait: See the difference a year made. By 1839, the chemicals were fast enough that a person could intentionally sit for a portrait.

The transition from the empty streets of the Boulevard du Temple to the crowded portraits of the 1840s happened faster than most people realize. We went from accidental ghosts to intentional icons in less than a decade.