Honestly, the first Olympics Athens 1896 wasn't the slick, high-tech global phenomenon we see today. Not even close. Imagine a scene where athletes didn't have official uniforms, some literally found out they were competing days before the events, and the "swimming pool" was actually just the freezing cold open water of the Bay of Zea. It was chaotic. It was messy. And yet, it somehow worked.

Pierre de Coubertin, the French baron who obsessed over the idea of reviving the ancient Greek games, didn't have an easy sell. People thought he was a dreamer. Or crazy. Or both. Europe was busy with geopolitical tension, and the idea of "peace through sport" sounded like a naive fairy tale. But when the gates of the Panathenaic Stadium opened on April 6, 1896, the world changed.

Why the First Olympics Athens 1896 Almost Never Happened

Money. It always comes down to money, doesn't it? The Greek government was basically bankrupt in the mid-1890s. Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis was a skeptic; he saw the games as an expensive distraction that the country simply couldn't afford. He wasn't wrong, strictly speaking. But the Crown Prince Constantine saw it differently. He headed the organizing committee and went on a massive fundraising blitz.

The savior of the games wasn't a government grant, but a wealthy businessman named Georgios Averoff. He donated about one million drachmas to restore the Panathenaic Stadium with white marble. That’s why the stadium looks so striking in those grainy old black-and-white photos. Without Averoff's deep pockets, the first Olympics Athens 1896 would’ve been a footnote in history books instead of a global milestone.

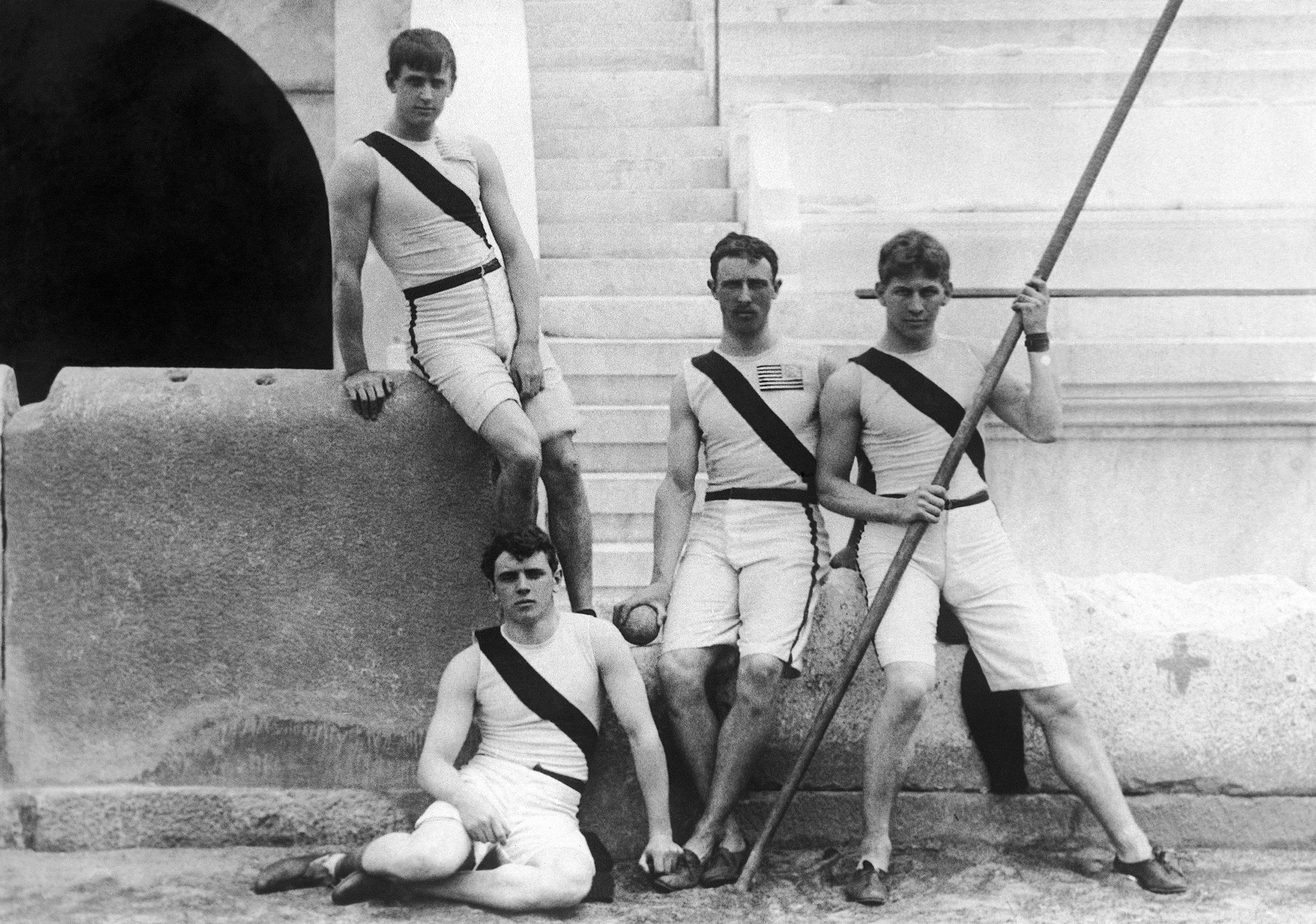

A Strange Mix of Athletes

The competitors weren't professional athletes. The concept of "professional" sports barely existed, and if it did, it was looked down upon by the aristocratic organizers. Most of the 241 athletes were amateurs—university students, members of local athletic clubs, or guys who just happened to be in town.

💡 You might also like: NFL Pick 'em Predictions: Why You're Probably Overthinking the Divisional Round

Take James Connolly, for example. He was a student at Harvard who wanted to compete so badly that he dropped out when the university refused to give him a leave of absence. He traveled by cargo ship and train, got his wallet stolen in Naples, and arrived in Athens just hours before his event. He won the triple jump. That made him the first Olympic champion in over 1,500 years. His prize? Not a gold medal. They didn't give those out yet. He got a silver medal and an olive branch.

The Events That Defined the Games

The program was pretty slim compared to the hundreds of events we have now. We're talking 43 events across nine sports: athletics, cycling, fencing, gymnastics, shooting, swimming, tennis, weightlifting, and wrestling.

The swimming events were particularly brutal. There was no heated indoor facility. The organizers took the athletes out into the Bay of Zea on a boat and basically told them to swim back to shore. The water was about 55 degrees Fahrenheit (13°C). Alfréd Hajós, a Hungarian swimmer who won two gold medals, later admitted that his "will to live completely overcame his desire to win." He coated his body in a thick layer of grease just to survive the cold. It wasn't about "optimal performance" in the modern sense; it was about not getting hypothermia.

The Marathon: A National Obsession

Nothing mattered more to the Greek hosts than the marathon. It was a brand-new race, inspired by the legend of Pheidippides. The Greeks hadn't won a single track and field event up to that point, and the local crowd was getting desperate.

📖 Related: Why the Marlins Won World Series Titles Twice and Then Disappeared

Enter Spyridon Louis.

He was a common water carrier. Not a trained runner. Legend says he spent the night before the race in prayer and fasting (though some accounts suggest he had a glass of wine or cognac during the race itself). When he entered the stadium for the final lap, the crowd of 80,000 went absolutely feral. Two Greek princes even ran alongside him to the finish line. It was the peak of the first Olympics Athens 1896, proving that the games could actually generate national pride and international headlines.

What People Get Wrong About 1896

We tend to romanticize the past. People think these games were a smooth transition from ancient to modern.

They weren't.

👉 See also: Why Funny Fantasy Football Names Actually Win Leagues

- Women weren't allowed. It's a massive stain on the legacy. Coubertin was famously sexist, calling the participation of women "impractical, uninteresting, unesthetic, and improper." A woman named Stamata Revithi tried to run the marathon course the day after the official race to prove a point, but she wasn't allowed into the stadium.

- The "Gold" Medal Myth. As mentioned, first place got silver, and second place got copper (or bronze). Gold medals weren't introduced until the 1904 games in St. Louis.

- The Attendance. While 80,000 people in the stadium sounds huge, the international participation was tiny. Only 14 nations were represented. Most of the "international" athletes were just expats or travelers who were already in the region.

The Long-Term Impact

The first Olympics Athens 1896 succeeded because it survived. If it had been a total flop, the IOC (International Olympic Committee) would have folded immediately. Instead, it created a blueprint. It showed that even with a shoestring budget and a haphazard group of participants, the "Olympic Spirit" had a weirdly infectious power.

But it wasn't all sunshine. The games immediately triggered a debate about where they should be held. Greece wanted them permanently. They felt they "owned" the brand. Coubertin disagreed; he wanted the games to rotate to different cities to make them truly "international." This tension nearly derailed the movement early on, leading to the poorly organized 1900 and 1904 games before the Olympics finally found their footing again.

Real Expert Insights on the 1896 Legacy

Historians like David Young, author of The Modern Olympics: A Struggle for Revival, emphasize that 1896 wasn't a "re-creation" of the ancient games, but a Victorian invention. The events, the rules, and even the marathon itself were products of the 19th-century imagination. We weren't looking back; we were building something entirely new that just happened to be wearing an ancient Greek costume.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you're a sports nerd or a history buff, you don't have to just read about this. You can actually engage with it.

- Visit the Panathenaic Stadium. It’s still there in Athens. You can walk on the marble. You can stand where Spyridon Louis finished his run. It is one of the few places in the world where the physical space of a 19th-century event remains largely unchanged.

- Dig into the Digital Archives. The IOC has digitized many of the original reports and photographs. Looking at the "official" report from 1896 is a trip—it reads more like a Victorian novel than a sports summary.

- Study the Medal Evolution. Look at the design of the 1896 medals compared to today. The 1896 medal featured Zeus holding Nike, the goddess of victory. It's a fascinating look at how the games used mythology to brand themselves.

- Watch the 1984 Miniseries. If you want a dramatized (but surprisingly accurate in spirit) look at the struggle to get the games off the ground, the TV miniseries The First Olympics: Athens 1896 is worth a hunt on streaming services.

The first Olympics Athens 1896 wasn't perfect. It was a gamble. But every time we watch the opening ceremony today, we're seeing the echoes of that weird, cold, marble-filled week in April 1896. It’s a reminder that big things usually start with a lot of confusion and one or two people who refuse to give up on a "crazy" idea.