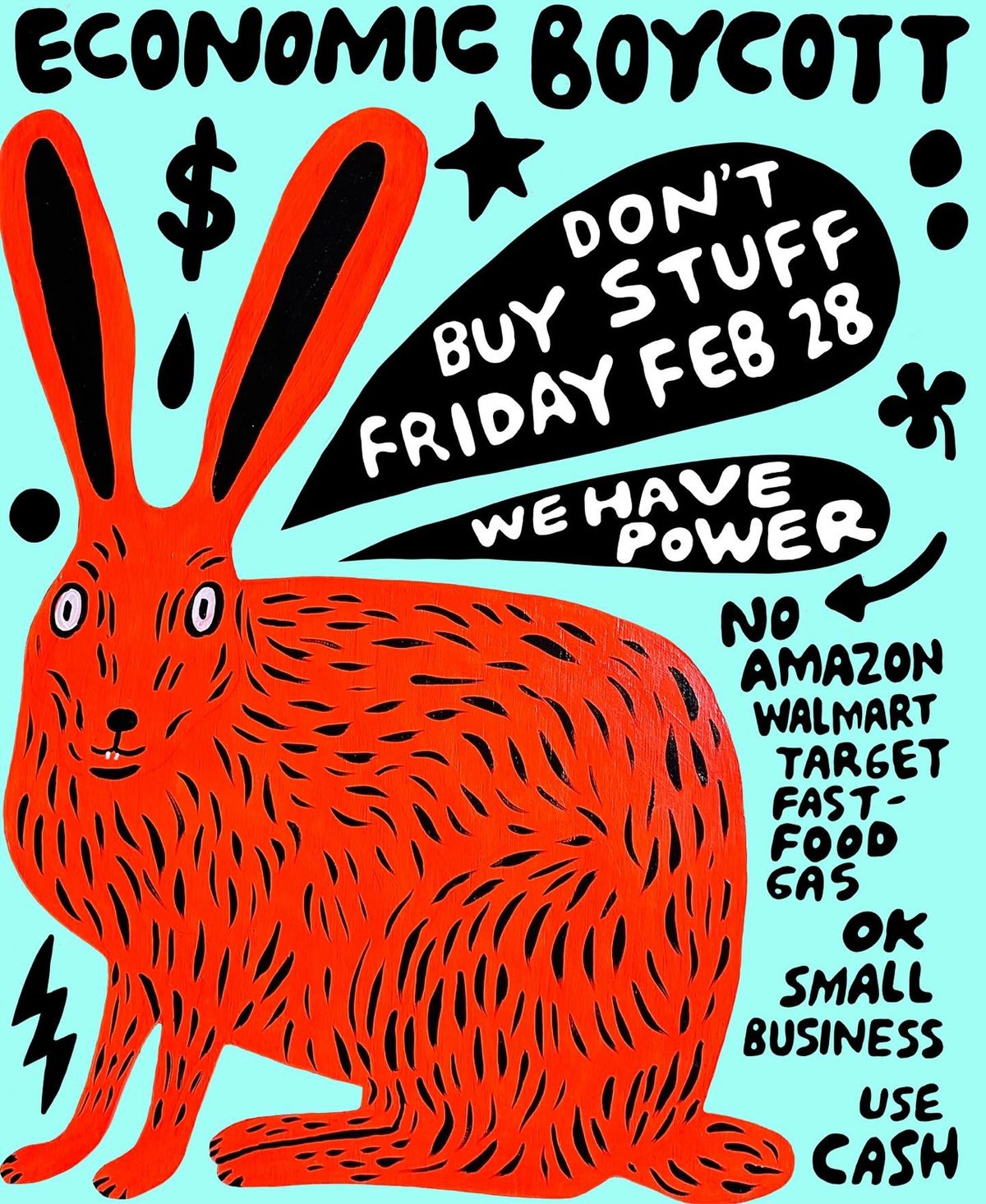

You've probably seen the flyers. They circulate every few months on TikTok, Instagram, and X, usually featuring bold red text and a list of demands that range from lower rent to a total overhaul of the global financial system. The February 28th economic blackout is the latest iteration of a digital-age phenomenon: the coordinated spending strike.

It sounds massive. On paper, millions of people stay home, log off, and keep their wallets shut for twenty-four hours to "send a message" to the powers that be. But honestly, if you look at the actual data from the retail and banking sectors during these specific dates, the reality is a bit more complicated—and a lot quieter—than the hashtags suggest.

What is the February 28th economic blackout actually trying to do?

The core idea is simple. In a consumer-driven economy, the only real leverage the average person has is their capital. By organizing a February 28th economic blackout, organizers aim to create a visible "dip" in the daily revenue of major corporations. They want to show that if the working class stops moving, the money stops flowing.

Usually, these calls to action focus on three main pillars. First, no shopping. That means no Amazon orders, no grocery runs, and definitely no Starbucks. Second, no work. This is the hardest part for most people to pull off, but the goal is a general strike where employees simply don't show up. Third, a digital "blackout" where users stay off social media platforms to tank ad revenue for the day.

It's a grassroots movement. There is no central "CEO of the Blackout," which is both its strength and its biggest weakness. It spreads through peer-to-peer sharing, fueled by genuine frustration over inflation, stagnant wages, and the rising cost of living that has made the 2020s feel like a constant uphill climb for the middle and lower classes.

💡 You might also like: Obituaries Binghamton New York: Why Finding Local History is Getting Harder

Does it actually hurt the bottom line?

Here is the truth: most economists don't even see these events on their charts.

Why? Because of "shifted consumption." If I know I’m participating in a February 28th economic blackout, I’m probably going to buy my bread and eggs on February 27th or March 1st. The total amount of money spent over the week remains exactly the same. For a multi-billion dollar retailer like Walmart or Target, a quiet Tuesday followed by a slammed Wednesday doesn't change their quarterly earnings report one bit. It’s a blip.

For a strike to work, it has to be sustained. One day is a gesture. A month is a movement.

When you look at successful economic boycotts in history—like the Montgomery Bus Boycott which lasted 381 days—the impact came from the duration. The February 28th economic blackout often struggles because it asks for a momentary pause rather than a fundamental shift in where people put their money. Plus, the logistical reality is that many people living paycheck to paycheck literally cannot afford to miss a day of work or skip a necessary purchase, even if they agree with the cause.

📖 Related: NYC Subway 6 Train Delay: What Actually Happens Under Lexington Avenue

The role of the "Algorithm" in social strikes

There’s a weird irony here. To organize a February 28th economic blackout, you have to use the very platforms you’re trying to protest. You need the TikTok algorithm to push your video. You need X to trend.

Social media companies actually benefit from the outreach phase of a blackout. The weeks leading up to February 28th usually see a spike in engagement as people argue about whether the strike will work. By the time the actual day rolls around, the platforms have already cashed in on the discourse.

Why the date matters

Choosing the end of February is strategic, though. It’s the end of the shortest month. People are usually broke after paying February’s rent and are looking toward March. It’s a dead zone for retail anyway. By branding it as a February 28th economic blackout, organizers tap into that natural end-of-month "broke" feeling that many people are already experiencing. It’s easier to participate in a spending strike when you don't have much left to spend anyway.

Comparing this to historical labor movements

If we look at the history of labor in the U.S. and Europe, real change usually comes from organized labor unions, not decentralized social media posts. The 1946 general strikes or the more recent UAW wins involved specific, legally protected bargaining units.

👉 See also: No Kings Day 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

The February 28th economic blackout is more of a "vibes-based" protest. It’s an expression of collective anger. While it might not tank the S&P 500, it does serve as a temperature check for the country. When thousands of people share a post about an economic blackout, it’s a signal to politicians and corporations that the public's patience with current economic conditions is wearing thin.

- Participation is fragmented: Some people just skip the mall; others try to go totally off-grid.

- Corporate response: Most major companies don't even acknowledge these specific strike dates publicly to avoid giving them more oxygen.

- The "Scab" problem: Unlike a factory strike where you can physically block an entrance, you can't stop millions of other people from shopping online during a digital blackout.

How to actually make an economic impact

If you’re frustrated with the state of the economy and want to do more than just participate in a one-day February 28th economic blackout, there are more effective ways to move the needle.

Stop buying from "Big Box" stores entirely and move your spending to local cooperatives. That hurts the giants and helps your neighbor. Move your money from a national "too big to fail" bank to a local credit union. This has a massive, measurable impact on how capital is distributed. Join a local tenant union or a labor union.

One day of silence is a start. But the economy is a 365-day machine.

To make a move like the February 28th economic blackout stick, it needs to transition from a "day of" event into a "way of life" change. It’s about permanent shifts in consumption. If you want to take action, start by auditing your own recurring subscriptions. Every dollar you pull back from a massive corporation is a vote for a different kind of system.

The real power isn't in what you don't do on February 28th. It's in what you choose to do every other day of the year. Focus on localizing your spending, supporting small-scale producers, and engaging in long-term organized labor efforts rather than relying on a single calendar date to do the heavy lifting.