We’ve all been lied to by Pink Floyd. Okay, maybe not lied to, but definitely misled by a very catchy album title. There is no permanent "dark side" of the moon. It just doesn't exist. If you were standing on the far side of the moon right now, you'd see the sun rise and set just like you would on the side we see from Earth. The difference is what's behind you. While the near side always looks back at our blue marble, the far side looks out into the vast, silent void of the cosmos. It’s lonely. It’s rugged. Honestly, it’s a completely different world than the one we think we know.

Why the Near Side and Far Side of the Moon Look Nothing Alike

Look at the moon through a pair of cheap binoculars. You see those big, dark patches? Those are "maria"—Latin for seas. Early astronomers thought they were actual oceans. They aren't. They are massive plains of ancient, solidified basaltic lava. The near side is covered in them. Roughly 30% of the surface we see is made of these smooth, dark basins. Now, look at the photos from the Soviet Luna 3 mission in 1959. That was the first time humans ever saw the far side of the moon. It was a shock.

There are almost no maria there. It’s just craters. Thousands of them. It looks like a battered shield that’s been taking hits for four billion years. This is what scientists call the "Lunar Farside Highlands Problem." For decades, researchers like Jason Wright at Penn State have been trying to figure out why the crust on the far side is so much thicker. It’s roughly 20 kilometers thicker than the side facing us.

Imagine the moon when it was still a glowing ball of molten rock. Because the moon is "tidally locked," the same side always faces Earth. Back then, the Earth was also incredibly hot—radiating heat like a giant space heater. The side of the moon facing Earth stayed hot and gooey, while the far side, facing the coldness of space, cooled down much faster. This allowed the crust to thicken up like the skin on a bowl of pudding left out on a counter. When meteors hit the far side later on, they just made dents. On the near side, they punched through the thin crust, letting lava bleed out and create those dark "seas" we see today.

The Quietest Place in the Solar System

There is a very specific reason why astronomers are obsessed with the far side of the moon. It has nothing to do with rocks or lava. It’s about the silence.

Radio silence, specifically.

💡 You might also like: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Earth is a noisy neighbor. We are constantly pumping out radio waves—Wi-Fi, cell signals, satellites, television broadcasts. All of this "electronic noise" makes it incredibly hard for radio telescopes on Earth to hear the faint signals from the early universe. But the moon is a massive, 2,000-mile-wide ball of rock. It acts as a perfect shield.

When you are on the far side of the moon, the entire bulk of the moon is blocking every single radio signal coming from Earth. It is the most "radio-quiet" spot in our local neighborhood. This is why China’s Chang’e 4 mission, which landed in the Von Kármán crater in 2019, carried low-frequency radio instruments. Scientists want to build a telescope there to listen to the "Dark Ages" of the universe—the time before the first stars even ignited.

Basically, the far side of the moon is our best chance at hearing the echoes of the Big Bang without Earth’s chatter getting in the way.

Gravity, Cracks, and the Strange South Pole-Aitken Basin

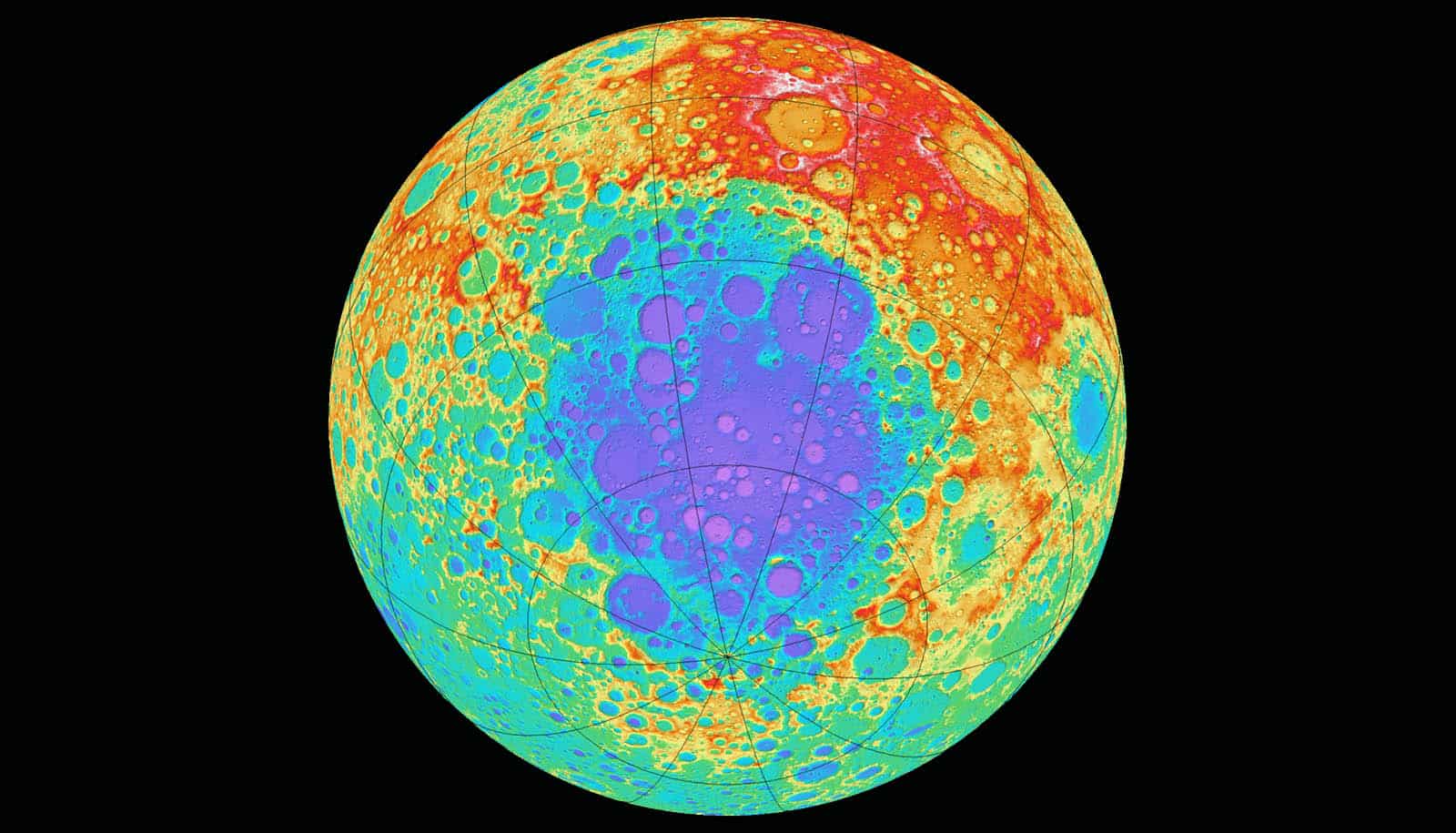

If you look at a topographic map of the moon, there’s a giant, bruised-looking purple spot at the bottom of the far side. This is the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin. It’s one of the largest, deepest, and oldest impact craters in the entire solar system. It’s about 1,500 miles wide and 8 miles deep.

If you dropped Mt. Everest into it, the peak wouldn't even come close to the rim.

📖 Related: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

This place is a goldmine for geologists. Because the impact was so violent, it likely peeled back the moon’s crust and exposed the mantle underneath. We aren't just looking at the surface there; we are looking at the guts of the moon. Recent data from NASA’s GRAIL mission—which used two spacecraft to map the moon’s gravity—showed something even weirder. There is a massive "lump" of metal buried under the SPA basin. It’s roughly five times the size of the Big Island of Hawaii.

Scientists think it might be the iron-nickel core of the asteroid that hit the moon billions of years ago, just stuck there in the mantle. Or it could be a massive concentration of oxides from the final stages of the moon's magma ocean cooling down. Either way, the gravity there is literally "heavier" than in other places.

Quick Comparison: Near Side vs. Far Side

- Near Side: Thin crust, dominated by volcanic plains (maria), high concentrations of heat-producing elements like Thorium and Potassium (the KREEP terrain).

- Far Side: Thick crust, almost entirely highland craters, very few volcanic plains, much higher elevation on average.

Living on the Other Side

If we ever build a base on the far side, it won't be easy. On the near side, you can always see Earth. You can point an antenna at it and talk to your family in real-time. On the far side, you are totally cut off. To communicate, you need "relay satellites" like China's Queqiao, which sits in a special orbit called an L2 point. It has a line of sight to both the far side and the Earth, bouncing signals back and forth like a cosmic game of telephone.

Then there’s the night.

A lunar "day" lasts about 29.5 Earth days. That means you get two weeks of blazing sunlight followed by two weeks of absolute, freezing darkness. On the far side, during those two weeks of night, you are truly alone. Temperatures drop to $-173^\circ\text{C}$ ($-280^\circ\text{F}$). Batteries die. Metals turn brittle. It’s a brutal environment that requires nuclear power or massive thermal storage to survive.

👉 See also: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

The Misconception of the "Dark Side"

We call it the dark side because it's dark to us—meaning "unknown." It’s not dark in terms of photons. During a New Moon, when the side facing Earth is dark, the far side is actually in full, glorious sunlight. It’s "High Noon" on the far side while we are looking up at a sliver of a crescent.

This confusion comes from tidal locking. The Earth's gravity has slowed the moon's rotation over billions of years until its orbital period matches its rotational period. It’s like a dancer holding their partner's hands and spinning in a circle; they always face each other. But the room around them—the sun—still shines on their backs at different times.

What’s Next for the Two Sides of the Moon?

We are entering a new era of lunar exploration. This isn't just about planting flags anymore. It's about resources. The far side, specifically near the poles, contains "cold traps"—craters that haven't seen sunlight in billions of years. We know there is water ice there.

Water isn't just for drinking. You can split it into Hydrogen and Oxygen. That’s rocket fuel. That’s air. The far side could eventually become a "gas station" for missions going to Mars.

If you want to keep up with what's happening, keep an eye on the Artemis missions. While Artemis II will carry humans around the moon, the long-term goal involves the Lunar Gateway—a small space station that will orbit the moon and provide a jumping-off point for landers heading to the far side and the South Pole.

Actionable Insights for the Space Enthusiast:

- Track the Phase: Use an app like "Lumos" or "Moon Phase" to see where the terminator line is. When you see a "New Moon," remember that the far side is currently experiencing total daylight.

- Explore the Imagery: Go to the LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) Quickmap. You can toggle between the near and far sides and see high-resolution imagery that shows just how rugged the far side actually is.

- Watch the News for "L2": Whenever you hear about a mission to the far side, listen for the mention of "Lagrange points." These are the invisible anchor points in space that allow us to keep satellites in place so we can talk to the "hidden" side of our neighbor.

The moon isn't just a dead rock. It’s a time capsule. The far side, with its thick crust and ancient craters, holds the record of the early solar system that Earth has long since erased through plate tectmatics and erosion. We are finally starting to read that record.