You’ve seen the paintings. Massive wings, gleaming swords, and a tragic, downward plunge into the abyss. It’s one of the most persistent images in Western culture. But honestly, if you try to find the play-by-play of the fall of the rebel angels in the Bible, you’re going to be looking for a long time. It isn't really there. At least, not in the way most people think it is.

We’ve basically stitched this story together. It’s a patchwork quilt of ancient Near Eastern mythology, cryptic poetic fragments, and—perhaps most importantly—17th-century fan fiction. When people talk about Lucifer’s pride or the one-third of the stars falling from the sky, they’re usually quoting John Milton’s Paradise Lost without even realizing it.

Where the story actually starts

The origins are messy.

In the Hebrew Bible, the concept of a "fallen angel" is actually pretty thin. You have the Nephilim mentioned in Genesis 6, where the "sons of God" saw that the daughters of men were beautiful and decided to come down for a closer look. This is the first real hint of a celestial defection. According to the Book of Enoch—which isn't in the standard biblical canon but was hugely influential—these were the "Watchers."

Led by figures like Semyaza and Azazel, these guys didn't just fall; they jumped. They wanted to teach humans things like metallurgy, cosmetics, and astrology. It’s less of a "war in heaven" and more of an unauthorized divine knowledge transfer. The punishment was severe, but the motivation was curiosity and lust rather than a coup d'état.

Then you have the linguistic mix-ups.

The name "Lucifer" appears in Isaiah 14:12. "How you are fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!" sounds like a smoking gun. However, most biblical scholars, including those at the Harvard Divinity School, will tell you Isaiah was actually trash-talking a human king of Babylon. The Latin word lucifer just means "light-bringer." It referred to the planet Venus. It wasn't a personal name for a devil until centuries later when early Christian theologians started connecting the dots between the arrogance of earthly kings and the perceived rebellion of heavenly beings.

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

The War in Heaven: Revelation and Milton

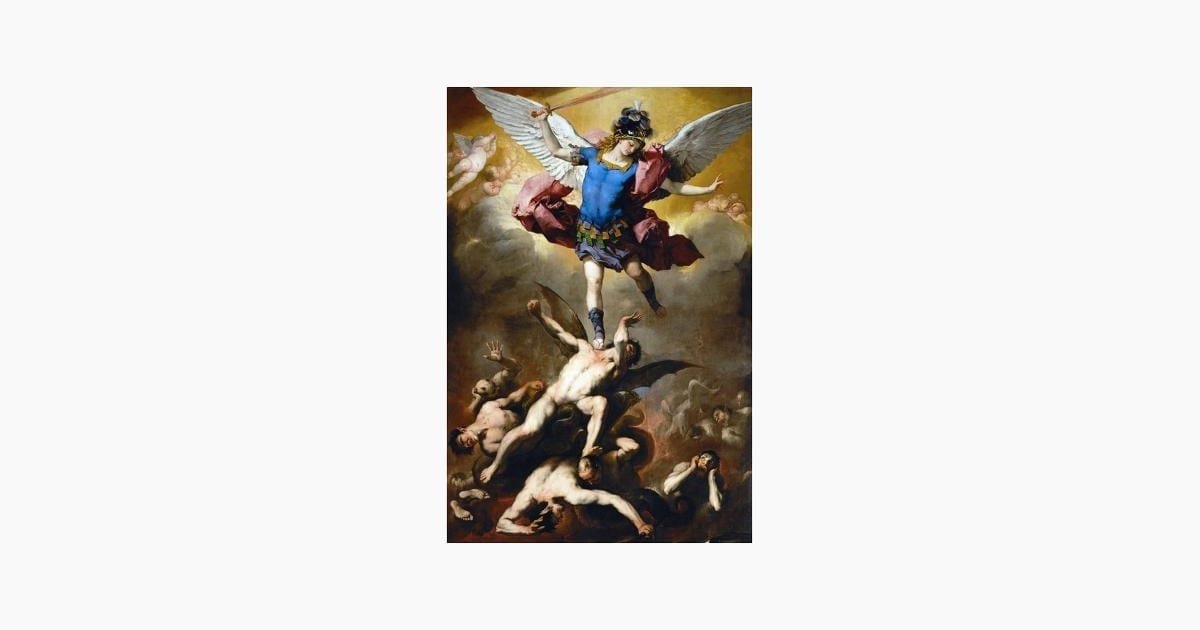

The actual "war" imagery comes primarily from the Book of Revelation, Chapter 12. This is where we get the dragon, the Archangel Michael, and the sweeping of a third of the stars from the sky.

"And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven."

It’s intense. It’s cinematic. But it’s also highly symbolic literature written during a time of intense Roman persecution.

By the time John Milton got his hands on the fall of the rebel angels in 1667, he turned this symbolic skirmish into a full-blown Greco-Roman epic. Milton is the one who gave Lucifer a personality. He’s the one who gave him the famous line about it being "better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven." That line isn't in the Bible. Neither is the detailed hierarchy of the rebel army. Milton took the bare bones of scripture and built a cathedral of psychological drama around them.

He made the rebels relatable. That’s the "human-quality" element that keeps this story alive in our collective gut. We understand pride. We understand the feeling of being passed over for a promotion—which, in Milton’s version, was the elevation of the Son of God over the other angels.

Why the "Third of the Stars" matters

The idea that exactly one-third of the angels fell is a staple of Sunday school lessons. This comes from Revelation 12:4: "His tail swept a third of the stars out of the sky and flung them to the earth."

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Is it a literal headcount? Probably not.

In ancient numerology, "one third" often just signified a significant, yet minority, portion. But for medieval demonologists, this was a math problem. They spent an absurd amount of time trying to calculate the exact number of fallen spirits. In the 15th century, Alphonso de Spina claimed the number was exactly 133,316,666. It's a strangely specific number for something nobody was there to count.

Art and the visual legacy

We can’t talk about the fall of the rebel angels without mentioning Pieter Bruegel the Elder. His 1562 painting is a chaotic masterpiece. It doesn't show beautiful men with wings; it shows a nightmare. As the angels fall, they transform into monstrous hybrids—part fish, part insect, part clockwork.

It captures the "ontological shift." The idea is that the fall wasn't just a change of location. It was a change of being. To rebel against the source of light was to literally lose one's form. This is a recurring theme in the writings of Thomas Aquinas, who argued that angels, being pure intellect, made their choice with such perfect clarity that it was irreversible. There’s no "sorry" in the pit.

Common Misconceptions

People often confuse different characters.

- Satan vs. Lucifer: In the Old Testament, "the satan" (ha-satan) is more of a title, like a "prosecuting attorney" in God's court. He's not necessarily a rebel yet.

- The Timing: Some traditions say the fall happened before the creation of the world. Others say it happened because of the creation of man (where the angels refused to bow to an "inferior" being made of dust).

- The Location: The "pit" or "Tartarus" mentioned in the New Testament (2 Peter 2:4) is where the rebels are supposedly chained. Yet, in the same breath, other verses describe the "prince of the power of the air." They are simultaneously imprisoned and roaming the earth, which is a theological contradiction that has fueled a thousand years of debate.

Modern cultural impact

Today, the fall of the rebel angels is more of a trope than a dogma. It’s the "Sympathy for the Devil" archetype. We see it in Lucifer on Netflix or in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. These versions lean heavily into the "tragic misunderstood rebel" angle, which is a far cry from the terrifying, non-human entities described in ancient Enochian texts.

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

The story persists because it’s the ultimate "what if?"

What if the most perfect beings ever created could still mess up? It’s a cautionary tale about ego, but it’s also a deeply human story about the consequences of choice.

Practical ways to explore this history

If you actually want to understand the layers of this story, don't just stick to a single source. The evolution of the narrative is where the real "truth" lies.

- Read the Book of Enoch: It’s available for free online. It’s weird, wild, and explains the "Watcher" tradition that the Bible mostly leaves out.

- Compare the Art: Look at Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Paradise Lost versus Bruegel’s painting. See how the "beauty" of the fallen angels changed over time.

- Check the Etymology: Look up the Hebrew word Helel (shining one) and see how it became the Latin Lucifer.

- Visit the Sources: If you're into academic rigor, the works of Dr. Elaine Pagels (particularly The Origin of Satan) provide a brilliant historical look at how these figures were used to demonize political enemies.

Understanding the fall of the rebel angels requires looking past the pop-culture version. It’s a story about the fragile nature of authority and the enduring power of the underdog—even when that underdog is a celestial being falling at terminal velocity.

To get the most out of this historical study, start by mapping the timeline of the texts. Read Genesis 6, move to 1 Enoch, then Isaiah 14, and finally Revelation 12. Seeing how the descriptions evolve from "divine beings marrying humans" to "dragons fighting in space" reveals exactly how our modern concept of the devil was constructed over two millennia. This chronological approach prevents the confusion of blending 17th-century poetry with 1st-century apocalypticism.