You’re standing in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. There’s a crowd, but honestly, it’s not the "Mona Lisa" kind of crowd where people are just checking a box. People are staring. They’re leaning in, squinting, trying to figure out if that’s a fish with wings or a lizard in a suit of armor. This is the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting, a 1562 masterpiece by Pieter Bruegel the Elder that feels less like a Renaissance religious scene and more like a fever dream captured in oil.

It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s a literal pile-on of celestial beings and biological nightmares.

For a long time, people actually thought this was a Hieronymus Bosch. You can see why. It has that same "world-ending-via-mutant-monsters" vibe. But when they found Bruegel's signature hidden under the frame in 1900, everything changed. This wasn't just a copycat at work; it was a genius taking a traditional Biblical story and turning it into a commentary on the sheer, grotesque reality of pride.

What is actually happening in the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting?

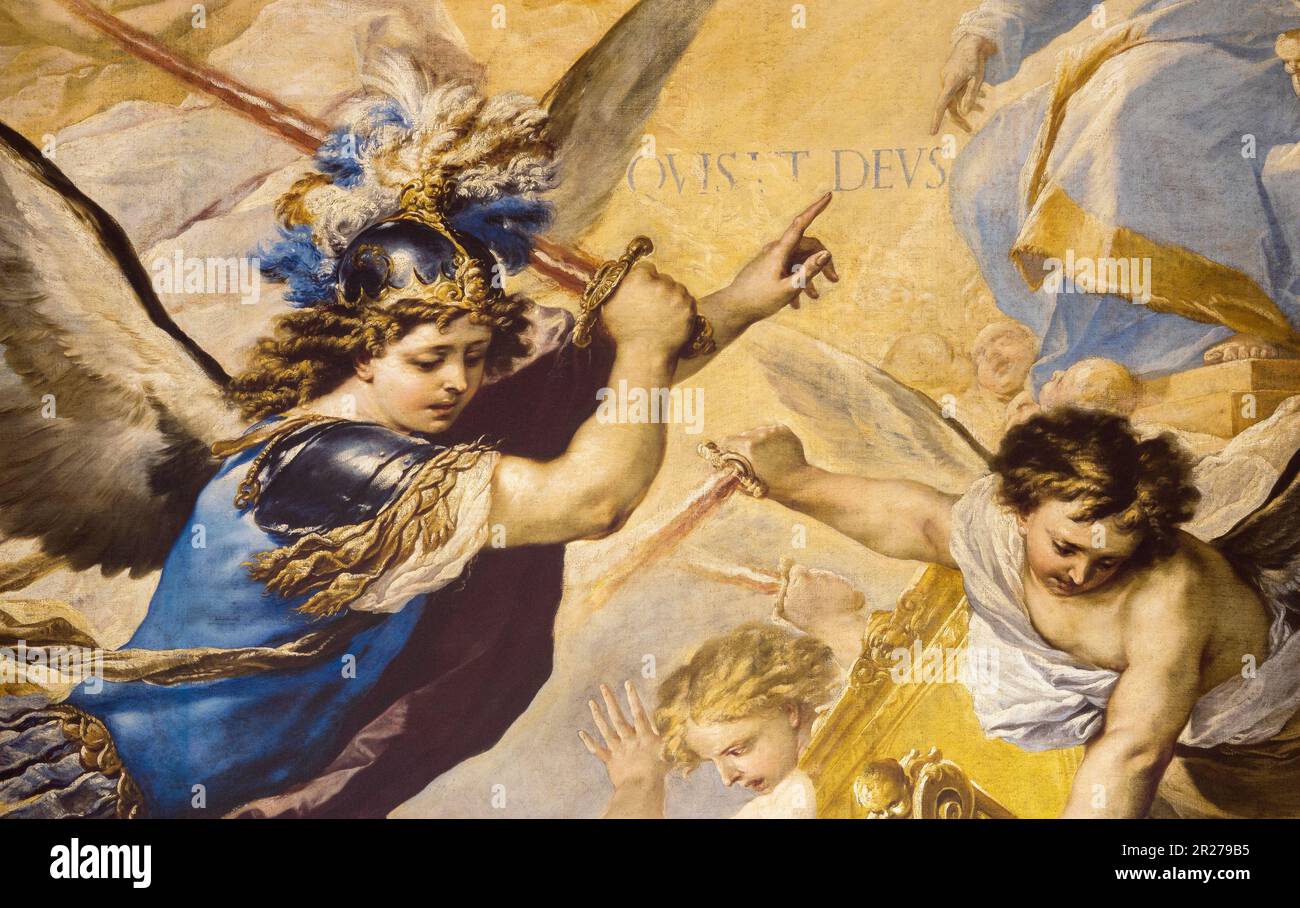

At its core, the painting depicts the moment Lucifer and his prideful followers are cast out of heaven. Archangel Michael is the star of the show here. He’s right in the center, wearing shimmering gold armor, looking oddly calm while he steps on a multi-headed dragon.

It’s a vertical struggle.

The top of the painting is a blinding, golden light—the pure atmosphere of heaven. But as your eyes move down, the light curdles. The angels who rebelled aren't just falling; they are physically transforming. They are becoming "things." Bruegel didn't just paint them as ugly people with wings. He turned them into hybrids of pufferfish, butterflies, sunbaked skeletons, and bloated shellfish.

One of the most jarring things about the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting is the sheer density of the composition. There is no "breathing room." Bruegel fills every square inch with limbs, wings, and scales. It’s claustrophobic. It makes you feel the weight of the fall. You aren't just watching a story; you’re trapped in the collapse.

The weird science behind the monsters

Bruegel was kind of a nerd for his time. The 16th century was the Age of Discovery. Explorers were coming back to Europe with weird stuff from the New World—dried armadillos, exotic birds, strange shells.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

Look closely at the demons.

That’s not just random imagination. He’s using actual biological details. He incorporates the anatomy of exotic animals to make the supernatural feel grounded in reality. This was a move of pure brilliance. By using "real" oddities, he made the spiritual fall feel like a physical, biological catastrophe. It’s the difference between a cartoon and a high-budget practical effect.

Why this isn't just another religious painting

Most Renaissance artists painted the Fall of the Rebel Angels as a clean, orderly battle. You’d have the good guys on the left and the bad guys on the right. Usually, the demons looked like standard-issue satyrs with horns and tails.

Bruegel rejected that.

He leans into the "grotesque." In the mid-1500s, the Netherlands was a powder keg of religious and political tension. The Spanish Inquisition was a very real threat. People were literally being torn apart for their beliefs. When you look at the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting through that lens, it stops being a Sunday school lesson and starts looking like a reflection of a world in total disarray.

Some art historians, like Tine L. Meganck, have argued that Bruegel was making a point about the dangers of intellectual pride. The "rebel angels" weren't just evil; they were arrogant. They thought they knew better than the source of all light. In an era of scientific discovery and religious upheaval, Bruegel was essentially asking: Do we actually know what we're doing, or are we just creating monsters?

The hidden details you probably missed

If you ever get to see this in person—or even in a high-res digital scan—look for the "Butterfly Angel." It’s one of the most beautiful and disturbing parts of the work. One of the falling rebels has wings made of delicate, colorful butterfly wings, but its body is a bloated, fleshy mess. It’s a stunning contrast.

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Then there’s the musical instruments.

Why are there trumpets and lutes in the middle of a cosmic war? Because music was associated with the harmony of heaven. By showing these instruments being tumbled and twisted among the demons, Bruegel shows the literal destruction of harmony. The world isn't just becoming evil; it’s becoming discordant. It’s noise.

The Bruegel vs. Bosch debate

We have to talk about Bosch. You can’t look at the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting without thinking of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

For centuries, Bruegel was nicknamed "Pieter the Droll" or "the second Bosch." It was almost a slight. People thought he was just a guy who liked drawing funny monsters. But there is a fundamental difference in how they approach the weird. Bosch’s monsters feel like they belong to a dream world. They are surreal.

Bruegel’s monsters feel like they belong to a laboratory.

His brushwork is more precise, his light is more naturalistic, and his understanding of space is more advanced. He took Bosch’s "weirdness" and gave it a 3D physical presence. When you look at the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting, you can almost smell the scales and the rotting fish. It’s visceral.

How to appreciate the painting today

If you want to actually "get" this painting, you have to stop looking at it as a whole and start looking at the fragments. It’s a collection of a thousand tiny tragedies.

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

- Focus on the colors: Notice how the palette shifts from gold to sickly greens and muddy browns.

- Look for the "Eye of the Storm": Find Michael. Notice how he isn't straining. The power isn't in his muscles; it’s in his position.

- The Silliness Factor: Don't be afraid to laugh. Bruegel included some genuinely absurd imagery. There’s a demon that’s basically an egg with legs. It’s okay to find the apocalypse a little bit funny.

The Fall of the Rebel Angels painting remains relevant because it captures a universal human fear: the loss of control. We live in a world that often feels like it’s tilting on its axis. We see structures collapsing and chaos taking over. Bruegel was the first artist to really capture what that feels like on a cosmic scale.

Taking the next steps with Bruegel

If this painting fascinates you, don't stop here. The 16th-century Flemish art scene is a rabbit hole of incredible detail. To truly master the context of this masterpiece, you should look into Bruegel’s other "dark" works.

Specifically, seek out The Dulle Griet (Mad Meg). It’s housed in the Mayer van den Bergh Museum in Antwerp. It’s even more chaotic and features a peasant woman charging into the mouth of Hell. It provides the perfect companion piece to the Rebel Angels.

You should also check out the digital "Bruegel Unseen Masterpieces" project by the Google Cultural Institute. They have ultra-high-definition scans where you can zoom in until you see the individual cracks in the paint. Seeing the texture of the "Butterfly Angel's" wings up close changes your entire perspective on Bruegel's technical skill.

Finally, if you're ever in Brussels, give yourself at least forty minutes with this one canvas. It takes that long for your eyes to adjust to the chaos and start seeing the brilliance in the mess. It isn't just a painting of a fall; it’s a warning about the beauty we lose when we let our own egos take the lead.

Actionable Insight: To understand the complexity of the Fall of the Rebel Angels painting, compare it directly to Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death. While Rebel Angels deals with a spiritual fall, Triumph of Death deals with the physical end of humanity. Seeing both will give you a complete picture of Bruegel’s philosophy on the fragility of the human (and angelic) condition.