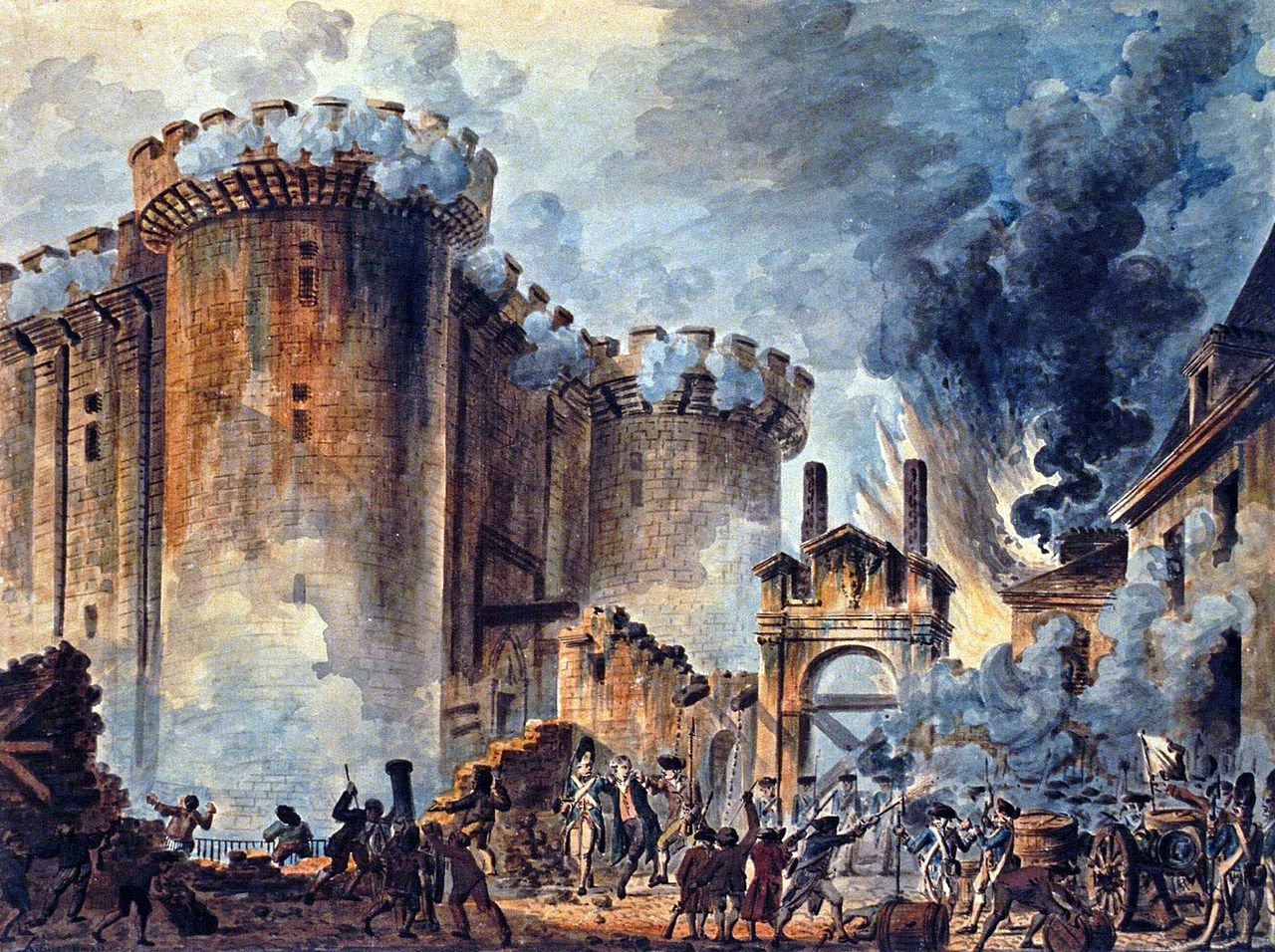

History is messy. We’ve all seen the paintings of the French Revolution—glorious, sweeping scenes of the Parisian masses charging a stone fortress with nothing but grit and muskets. It’s a great story. But the reality of the fall of the Bastille is a bit more complicated, a bit more chaotic, and honestly, a lot more human than your high school textbook probably let on. It wasn't just a sudden burst of "liberty, equality, fraternity." It was a day of panicked confusion, terrible heat, and a series of massive tactical blunders that changed the world forever.

Paris in July 1789 was a tinderbox. People were starving. Bread prices had soared so high that a loaf cost about a week’s wages for a laborer. Imagine that. You work for six days straight just to buy one baguette. King Louis XVI, who wasn't exactly a master of reading the room, had started moving troops into the city. When he fired Jacques Necker—the finance minister the public actually liked—the city finally snapped.

The Bastille wasn't even the primary target at first. People needed gunpowder. They had already raided the Hôtel des Invalides and made off with thousands of muskets, but those guns are just heavy clubs without powder. They knew where the powder was stored. It was tucked away in the thick, eight-towered walls of a medieval fortress that doubled as a prison.

Why the Fall of the Bastille Wasn't the Movie Scene You Imagine

If you walked into the Bastille on the morning of July 14, you wouldn't find hundreds of political prisoners rotting in chains. In fact, there were only seven people locked up. Seven. Four of them were forgers, two were mentally ill, and one was a "deviant" aristocrat being held at his family's request. Hardly the epicenter of royal tyranny.

The governor of the Bastille, Bernard-René de Launay, wasn't a monster. He was actually quite terrified. He had a small garrison of about 80 Invalides (veteran soldiers with minor disabilities) and 30 Swiss Guards. He spent the morning trying to negotiate. He even invited the leaders of the crowd inside for lunch. They sat there eating while thousands of angry Parisians stood outside in the sun, getting more impatient by the second.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The Moment the Shooting Started

Mistakes happen in war. Around 1:30 PM, a few men managed to climb onto a roof and cut the chains to the drawbridge. It crashed down, crushing one person and letting the mob into the outer courtyard. De Launay, seeing the crowd rush in, panicked. He ordered his men to fire. This was the point of no return.

Once the first shots were fired, the fall of the Bastille became a bloodbath. The crowd felt betrayed. They thought they had been invited in, only to be ambushed. For a few hours, it was a stalemate. The fortress walls were too thick for the mob's muskets to do anything. Everything changed when a group of French Guards—professional soldiers who had deserted the King—showed up with five cannons. They pointed the big guns at the main gate.

De Launay realized it was over. He threatened to blow up the entire fortress, powder and all, which would have leveled half the neighborhood. His own men talked him out of it. He surrendered, the drawbridge came down, and the crowd surged in.

A Bloody Aftermath

The "glory" of the day was immediately stained. Despite promises of safe passage, De Launay was dragged through the streets toward the Hôtel de Ville. He was beaten, stabbed, and eventually killed. His head was put on a pike. This became a gruesome trend for the French Revolution. It wasn't just a political shift; it was the birth of a specific kind of public violence that eventually led to the Reign of Terror.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The Myth vs. The Reality of the French Revolution

We talk about the fall of the Bastille as this monumental victory over a crushing dictatorship. In reality, the prison was already scheduled for demolition because it was too expensive to maintain. Louis XVI didn't even realize how bad the situation was. His diary entry for that day famously reads: "Rien" (Nothing). He was referring to his unsuccessful hunt that morning, not the revolution. Talk about a lack of situational awareness.

- The Prison Population: As mentioned, only seven prisoners.

- The "Storming": It was more of a surrender after a standoff.

- The Casualties: About 98 attackers died, but only one defender died during the actual fighting.

- The Key: The key to the Bastille currently lives at Mount Vernon. The Marquis de Lafayette sent it to George Washington in 1790 as a souvenir of liberty.

What really matters is the symbolism. The Bastille represented the Ancien Régime. By tearing it down—and the Parisians literally tore it down by hand, stone by stone, over the following months—they were dismantling the old world. It was a psychological victory.

The Long-Term Impact on French Politics

The fall of the Bastille did more than just get people some gunpowder. It forced the King to recognize the National Assembly. It proved that the people of Paris were now a political force that couldn't be ignored. Within weeks, the Assembly abolished feudalism and adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

But it also set a dangerous precedent. It showed that "the mob" could get results through violence. This tension between democratic ideals and street violence defined the next decade of French history. You see it in the rise of Maximilien Robespierre and the eventual rise of Napoleon Bonaparte.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

If you look at modern France, Bastille Day (July 14) is still the biggest holiday. But they don't call it Bastille Day. They call it La Fête Nationale. Interestingly, the holiday actually commemorates the Fête de la Fédération in 1790, a massive feast held a year after the fall, intended to celebrate peace and national unity. It’s a bit of a historical pivot—commemorating the party that celebrated the event, rather than the bloody event itself.

How to Explore this History Today

If you go to Paris today looking for the Bastille, you won't find it. There is a square called Place de la Bastille and a massive "July Column," but that column actually commemorates a different revolution in 1830.

To really get a feel for the fall of the Bastille, you have to look closer:

- The Cobblestones: At the Place de la Bastille, look for the triple row of paving stones on the ground. They mark where the fortress walls used to stand.

- The Metro: If you take Line 5 to the Bastille station, you can see remains of the fortress walls built into the platform.

- The Carnavalet Museum: This is the best place to see artifacts from the revolution, including models of the prison carved from its own stones.

Understanding this event requires acknowledging that it wasn't a clean victory. It was a messy, loud, and violent day born of desperation. The people weren't looking to start a ten-year war; they were looking for bread and a way to defend themselves against a King who seemed to have forgotten they existed.

The fall of the Bastille serves as a reminder that systems of power are often more fragile than they look. A fortress that stood for hundreds of years fell in a single afternoon because the people inside lost their nerve and the people outside lost their patience.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

To truly grasp the weight of the French Revolution, don't just read the summary of the fall of the Bastille. Look at the primary sources.

- Read the Cahiers de Doléances: These were "books of grievances" written by ordinary French people before the revolution. They give you a direct look at the hunger and frustration that fueled the mob.

- Trace the stones: If you're in Paris, walk from the Invalides to the Bastille. It’s a long walk. Imagine doing it while carrying a heavy musket, in the July heat, surrounded by thousands of screaming people.

- Analyze the media: Look at the "libelles" (pamphlets) of the time. They were the 18th-century version of viral social media posts, filled with rumors and scandals that did more to destroy the monarchy's reputation than any political speech.

- Compare perspectives: Read the account of the event by Jean-Claude-Blaise de la Flotte alongside the official royal reports. The discrepancies show how "fake news" and propaganda have always been part of political upheaval.