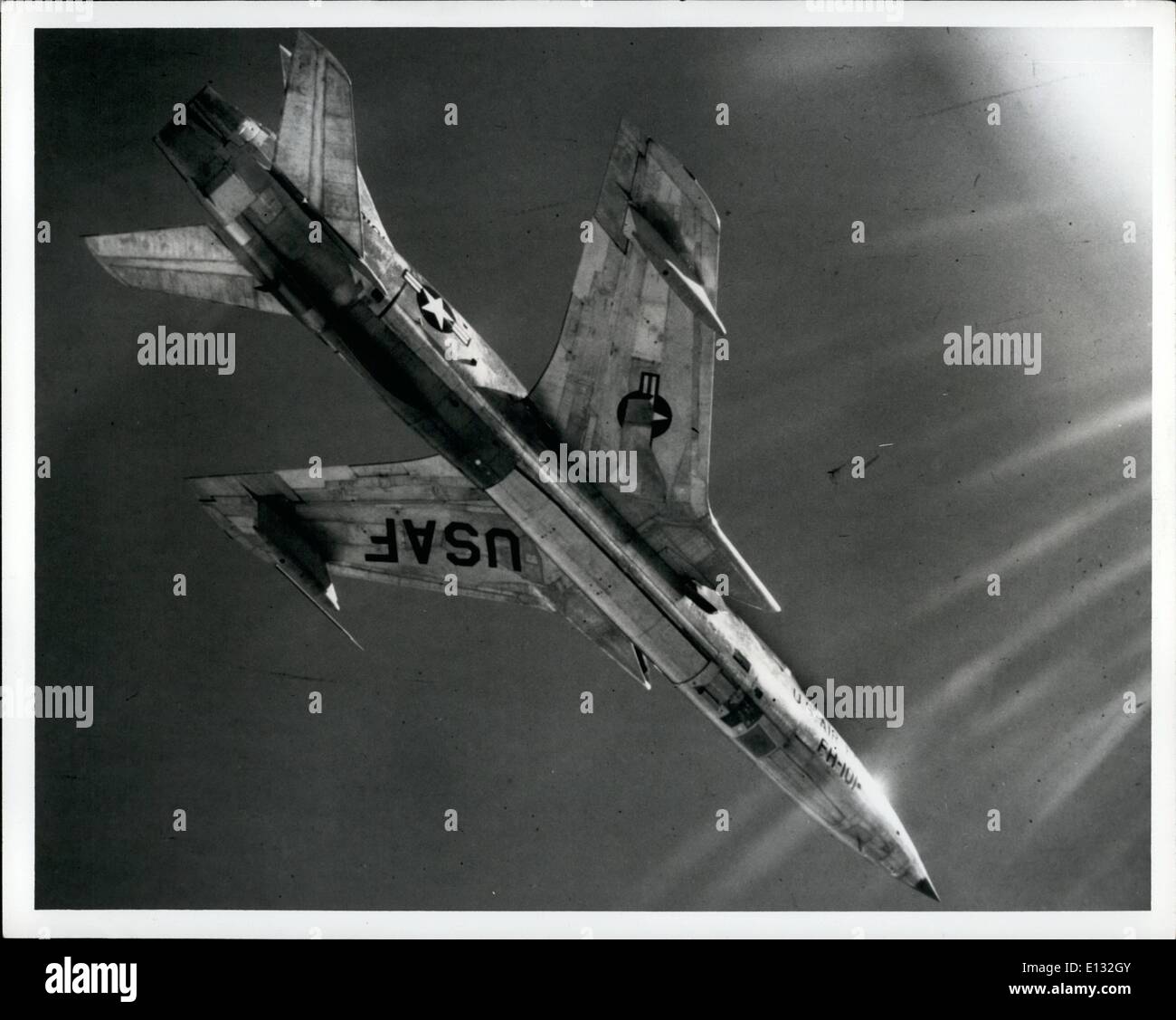

Pilots called it the "Thud." That nickname wasn't exactly a compliment at first, mostly because that was the sound it made when it hit the ground. It was massive. It was heavy. It was arguably one of the most complex pieces of machinery ever sent into a high-intensity conflict. If you stood next to an F-105 Thunderchief, the first thing you’d notice is the sheer scale of the thing; it’s basically a 64-foot-long engine with some wings and a cockpit strapped on top.

Republic Aviation designed this beast for a very specific, very terrifying job: flying at treetop level at supersonic speeds to drop a single nuclear bomb on a Soviet target. It was a one-trick pony. But history had other plans. Instead of a nuclear sprint over Europe, the F-105 Thunderchief became the primary tactical bomber of the Vietnam War, a role it was never meant to play and one that eventually cost the Air Force nearly half of the entire fleet.

Why the F-105 Thunderchief was a technological marvel (and a nightmare)

People talk about "over-engineering," but the Thud took it to a different level. It was the largest single-seat, single-engine combat aircraft in history. To get that much weight off the ground and through the sound barrier at low altitude, Republic used the Pratt & Whitney J75-P-19W engine. It produced about 24,500 pounds of thrust with the afterburner kicking.

Speed was its only real defense.

The wings were tiny and swept back at a sharp 45-degree angle. This made it stable at high speeds but turned it into a "lead sled" when things got slow or when it tried to turn. If you were a North Vietnamese MiG pilot, you didn't want to chase a Thud in a straight line—you'd never catch it. But if you could force it into a dogfight? It was a different story.

One of the most fascinating bits of tech was the "Area Rule" fuselage. If you look at the middle of the plane, it cinches in like a wasp waist. This wasn't for aesthetics. It reduced transonic drag, allowing the F-105 Thunderchief to maintain Mach 1+ speeds while carrying a massive internal payload. Most fighters carry bombs on the wings, which creates drag. The Thud had an internal bomb bay, though in Vietnam, that bay usually held an extra fuel tank because the plane was incredibly thirsty.

The terrifying reality of Rolling Thunder

During Operation Rolling Thunder, the F-105 carried the brunt of the strike missions. It flew more than 75% of the bombing sorties over North Vietnam. Think about that for a second. One single aircraft type was responsible for almost the entire air campaign's heavy lifting for years.

✨ Don't miss: Project Liberty Explained: Why Frank McCourt Wants to Buy TikTok and Fix the Internet

The environment was brutal. North Vietnam had the most dense integrated air defense system (IADS) in the world at the time. You had SA-2 Guideline missiles, heavy anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), and nimble MiGs all trying to swat these heavy bombers out of the sky.

The loss rates were staggering.

By the time the F-105 was pulled from frontline service, 382 aircraft had been lost. Out of 833 produced, that’s nearly 50%. Pilots like Leo Thorsness and Merlyn Dethlefsen earned Medals of Honor flying the "Wild Weasel" version of the Thud, the F-105G. Their job was essentially to act as bait, letting North Vietnamese radar operators "paint" them so they could fire Shrike anti-radiation missiles back down the beam. It was basically a high-stakes game of chicken at 600 knots.

The internal struggle of the Republic design

Honestly, the Thud was a victim of its own systems. It used a complex hydraulic system that was famously fragile. Because the aircraft was so tightly packed, a single piece of shrapnel from a lucky AAA hit could sever both the primary and utility hydraulic lines. When that happened, the flight controls locked up.

The pilot became a passenger in a multi-million dollar lawn dart.

Later modifications added "armor" and backup systems, but the reputation stuck. Yet, despite the losses, pilots grew to love the thing. It was rugged in every way except those hydraulics. It could take a beating from 37mm or 57mm cannons and keep flying, provided the lines stayed intact. There are legendary stories of Thuds returning to base with half a wing missing or holes in the fuselage big enough to crawl through.

🔗 Read more: Play Video Live Viral: Why Your Streams Keep Flopping and How to Fix It

Wild Weasels and the Birth of Electronic Warfare

You can't talk about the F-105 Thunderchief without mentioning the "Wild Weasels." This was a specific mission profile (SEAD - Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses). The F-105F and G models were two-seaters. The guy in the back was the Electronic Warfare Officer (EWO), or "Bear."

They hunted SAM sites.

It was a specialized, incredibly dangerous niche. They used the AN/APR-35/36 receivers to sniff out the "Fan Song" radars of the SA-2 missiles. Once they found them, they didn't just bomb them; they stayed in the area to keep the radars busy so the "strike" Thuds could get in and out. "First In, Last Out" was their motto. It wasn't just bravado; it was a tactical necessity.

Comparing the Thud to the F-4 Phantom

Most people think of the F-4 Phantom II as the icon of Vietnam. And sure, the Phantom was more versatile and eventually took over the strike role. But the F-105 was actually a better bombing platform in many ways. It was more stable at high speeds and low altitudes, which made it a more accurate "truck" for unguided iron bombs.

The F-4 was a Navy interceptor forced into a multi-role life. The F-105 was a purpose-built nuclear delivery system forced into a conventional war.

- Speed: F-105 was faster at low levels.

- Payload: The Thud carried up to 14,000 lbs of ordnance.

- Armament: It had a 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon—something the early F-4s lacked, much to the chagrin of their pilots.

That 20mm cannon turned out to be a lifesaver. Even though it wasn't a dogfighter, F-105 pilots officially credited themselves with 27.5 MiG kills. Most of those were with the gun. When a Thud pilot got a MiG in his sights, the high rate of fire from the Vulcan usually meant the end for the lighter, more fragile Soviet-made jets.

💡 You might also like: Pi Coin Price in USD: Why Most Predictions Are Completely Wrong

Why it didn't survive the 1970s

By the end of the war, the F-105 airframes were just tired. They were "timed out." The constant high-G maneuvering and the stress of low-level supersonic flight had literalized the "Thud" nickname—the metal was fatigued. The Air Force started shifting to the F-4 and eventually the F-111, which could carry more and fly at night/in bad weather using terrain-following radar.

The Thud stayed in service with the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard until 1984, but its day in the sun (or the humid clouds of Hanoi) was over.

It remains a polarizing aircraft. To some, it’s a symbol of failed Pentagon procurement—a plane designed for the wrong war. To the men who flew it, it was a beast that required a "real pilot" to handle. It didn't have computer-assisted flight controls. It was heavy, fast, and unforgiving.

Actionable insights for aviation enthusiasts and historians

If you're looking to dive deeper into the history of the F-105 Thunderchief, don't just look at the stat sheets. The real story is in the operational history.

- Visit the Museums: If you want to see one in person, the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, has a stunning F-105D and a Wild Weasel G model. Seeing the size of the landing gear alone tells you everything you need to know about its weight.

- Read the Primary Accounts: Look for "Thud Ridge" by Col. Jack Broughton. It’s a raw, controversial look at the air war from the cockpit of an F-105. It highlights the friction between the pilots and the politicians in Washington who were picking targets.

- Study the SEAD Evolution: The tactics developed by the F-105 Wild Weasels are still the foundation for how the F-35 and F-16CJ operate today. The gear has changed, but the "bait and strike" philosophy started right here.

- Check the Serial Numbers: Many F-105s on display across the US are veterans of 100+ missions over North Vietnam. You can often track an individual aircraft's combat history through the Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) records.

The F-105 Thunderchief was a bridge between the old-school "century series" fighters and the modern multi-role jets we see today. It was flawed, fast, and fierce. It took a specific kind of courage to strap into a 50,000-pound jet that was known for having "brick-like" gliding characteristics and fly it into the teeth of the most dangerous airspace on earth.