If you’ve watched the movie, you probably felt that lump in your throat when Ernie Davis finally hoists the Heisman. It’s a powerful scene. But honestly, Hollywood has a habit of "improving" on reality to the point where the real guy gets lost in the cinematic sauce. The Express: The Ernie Davis Story is a solid flick, but the man behind the jersey was much more interesting—and his life was far more complicated—than a two-hour runtime can really capture.

He wasn't just a football player. He was a symbol.

Ernie Davis didn't just break records; he broke a ceiling that had been reinforced with steel and prejudice for decades. People call him the "Elmira Express," a nickname that stuck because he ran like a freight train with no brakes. But off the field? He was quiet. Respectful. Almost famously humble.

The Real Syracuse Years (It wasn't all just touchdowns)

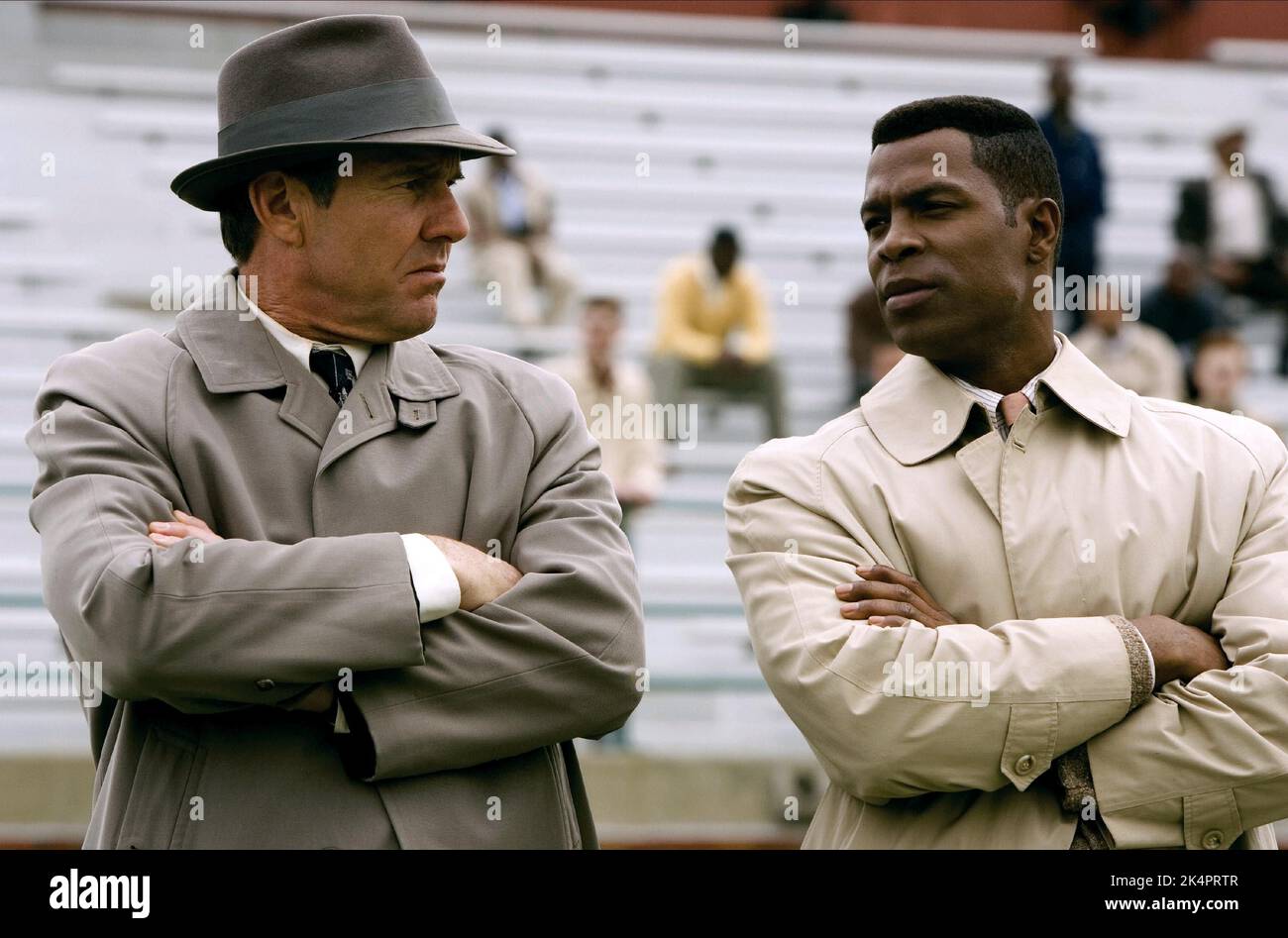

When Ernie showed up at Syracuse University, he was stepping into the shoes of Jim Brown. That’s not a "big shoes to fill" situation—that’s a "trying to fill a canyon" situation. Jim Brown was a force of nature. Coach Ben Schwartzwalder, played by Dennis Quaid in the movie, was a hard-nosed paratrooper from WWII who didn't care about your feelings. He cared about winning.

The movie makes it look like Ben and Ernie were constantly at each other's throats. In reality? Most of those who played for Schwartzwalder say Ernie was incredibly respectful. He wasn't the type to scream at his coach in front of the team. That’s a Hollywood trope used to create "character growth."

✨ Don't miss: Mizzou 2024 Football Schedule: What Most People Get Wrong

During the 1959 season, Syracuse was untouchable. They went 11-0. Davis was a sophomore, and he was averaging roughly 7.0 yards per carry. Think about that for a second. Every time he touched the ball, he was basically guaranteed a first down every two plays.

What the Movie Got Wrong About the 1960 Cotton Bowl

Here is where the film takes its biggest creative liberties. If you’ve seen the movie, you remember the "hostile" game at West Virginia and the brutal, racially charged atmosphere of the Cotton Bowl against Texas.

Here is the truth:

- The West Virginia Scene: In the movie, the fans are throwing trash and screaming slurs. In reality, that 1959 game was played in Syracuse, not West Virginia. The fans in Morgantown were actually fairly respectful to Davis when he played there the following year.

- The Cotton Bowl Segregation: This part is sadly true. After Syracuse beat Texas 23-14, Ernie Davis was named the MVP. But he was told he couldn't stay for the banquet at the segregated Dallas hotel. He was told to accept his award and leave.

- The Team's Response: The movie shows the whole team refusing to attend. The reality is a bit more nuanced. There was a huge debate. Some teammates wanted to boycott, but school officials eventually made the call. Davis and the other Black players ended up at a local barbecue joint while the rest of the team attended the official function. It was a stinging reminder that even as a national champion, he wasn't "equal" in the eyes of the law.

The Tragedy of the Cleveland Browns

The ending of The Express: The Ernie Davis Story is a gut punch. After being the first African American ever to be drafted #1 overall in the NFL, Ernie was traded to the Cleveland Browns. The plan was to pair him with Jim Brown.

🔗 Read more: Current Score of the Steelers Game: Why the 30-6 Texans Blowout Changed Everything

It would have been the greatest backfield in the history of the sport. Period.

But it never happened. During the summer of 1962, while preparing for the College All-Star game, Ernie started feeling tired. His gums were bleeding. He thought it was the heat or maybe the mumps. It was acute monocytic leukemia.

He was only 23.

There’s a heartbreaking detail that the movie glosses over: Ernie actually went into remission for a while. He felt great. He was practicing. He desperately wanted to play. Browns owner Art Modell wanted him to play, too. But Coach Paul Brown (a different Brown, keep up) refused. He wouldn't let a dying man on the field, fearing the liability and the "distraction." It created a rift that eventually helped lead to Paul Brown being fired.

💡 You might also like: Last Match Man City: Why Newcastle Couldn't Stop the Semenyo Surge

Why Ernie Davis Still Matters in 2026

We talk about Jackie Robinson a lot. We should. But Ernie Davis was doing the same work in a different arena. He won the Heisman in 1961, a time when the Civil Rights Movement was hitting a boiling point. He met President John F. Kennedy. He showed a generation of young Black athletes that the highest individual honor in college sports wasn't off-limits.

Honestly, the most impressive thing about Ernie wasn't the 2,386 rushing yards. It was how he handled the end. He knew he was dying. He wrote a piece for the Saturday Evening Post where he basically said he wasn't "unlucky." He felt he'd lived a full life because he got to do what he loved.

Fact-Checking The Express: The Movie vs. The Man

| Feature | Movie Depiction | Historical Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship with Coach | High-tension, confrontational | Deeply respectful, almost father-son |

| West Virginia Game | Violent, racist mob in WV | Played in Syracuse; mostly peaceful |

| Draft Day | Drafted by Browns | Drafted #1 by Redskins, then traded |

| The Cotton Bowl | Full team boycott | Mixed reaction; school officials intervened |

How to Honor the Legacy Today

If you’re a fan of the story, don’t just stop at the credits of the movie. The film is a gateway, but the real history is deeper.

- Read the Biography: Check out The Elmira Express by Robert C. Gallagher. It’s the book the movie was based on, and it’s much more factually grounded.

- Visit Syracuse: If you’re ever in Upstate New York, the statue of Ernie Davis at Syracuse University is a must-see. He’s wearing that iconic number 44.

- Support Leukemia Research: Ernie’s life was cut short by a disease we’ve made huge strides in treating since 1963. Supporting organizations like the LLS (Leukemia & Lymphoma Society) is the most direct way to honor his memory.

Ernie Davis didn't need Hollywood to make him a hero. He already was one. He was a man who ran through tackles and social barriers with the same level of grace. Even if the movie gets the geography of a game wrong or adds a fake argument for "drama," the core of the story remains: Ernie Davis was the best of us.

Next Step: You should look up the history of the number 44 at Syracuse. It’s a "sacred" jersey worn by Jim Brown, Ernie Davis, and Floyd Little. Understanding that lineage makes Ernie's place in the story even more impressive.