Don and Phil Everly were usually the kings of the teenage heartbreak anthem, but in 1959, they pivoted to something a bit darker. Most people think of them in the context of "Bye Bye Love" or the soaring harmonies of "All I Have to Do Is Dream." Then there is The Everly Brothers Take a Message to Mary, a song that feels less like a soda shop slow-dance and more like a scene pulled straight from a gritty Western film. It’s a song about a jailbird. Specifically, a guy who messed up, ended up behind bars, and is now trying to lie to his girlfriend so she doesn't find out he's a criminal.

It’s heavy.

The track was written by the legendary songwriting duo Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. They were basically the architects of the Everly sound. But this particular song, released as a B-side to "Poor Jenny" before becoming a hit in its own right, tapped into a weirdly specific American trope: the honorable outlaw. You’ve probably heard it a thousand times on oldies radio, but when you actually listen to the lyrics, it’s kinda heartbreaking. The narrator is begging a friend to go back home and tell Mary he's "traveling," not rotting in a cell.

Why the Song Hit Differently in 1959

By the late fifties, rock and roll was losing its edge a little. Buddy Holly was gone. Elvis was in the Army. The Everly Brothers were stuck in this transition period where they had to remain "clean-cut" while still appealing to the rebellious spirit of youth culture. The Everly Brothers Take a Message to Mary managed to bridge that gap perfectly. It wasn't a "bad boy" song in the sense of leather jackets and motorcycles; it was a song about regret.

✨ Don't miss: The Donna Twin Peaks Actress Dilemma: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The production is what really sells it. If you listen closely, you’ll hear a metallic clinking sound throughout the track. That isn't a standard percussion instrument. It’s actually someone—likely a studio hand or one of the musicians—hitting a screwdriver against a Coke bottle. It was meant to mimic the sound of a hammer hitting a limestone rock in a prison quarry. It’s subtle, but it gives the whole track this rhythmic, grinding feeling of manual labor and confinement.

Don and Phil’s harmonies are, as always, tight enough to make your hair stand up. But here, they use a softer, almost hushed delivery. They aren't belting. They’re whispering a secret. They are the voice of the friend who has to carry this lie back to Mary.

The Bryant Connection

Felice and Boudleaux Bryant weren't just songwriters; they were storytellers who understood the Everly's vocal range better than anyone. They knew that Don’s lower register and Phil’s high tenor could sell a narrative of shame. Most pop songs of the era were about "I love you" or "You left me." The Bryants gave them something more complex: "I love you, but I'm too ashamed to let you see what I've become."

The Narrative Structure: A Lesson in Lying

The lyrics are structured as a series of instructions.

"Take a message to Mary, but don't tell her where I am."

That’s the opening hook. Right away, the listener is curious. Where is he? Why is he hiding? As the song unfolds, we learn the narrator "started out to see the world, but I went about it wrong." It’s such a polite, almost sanitized way of saying he committed a crime. The ambiguity is what makes it work. We don't know if he robbed a bank or got into a bar fight that turned sideways. All we know is he’s looking at a long stretch of time.

There’s a specific line that always hits home: "Tell her that I'm overseas, a-sailin' on the seven seas."

He’s asking his friend to paint a picture of adventure to cover up a reality of iron bars. Honestly, it’s one of the most effective uses of irony in early rock-pop. The contrast between the breezy, adventurous lie and the repetitive clink of the "prison hammer" creates a tension that most songs from 1959 simply didn't have.

Realism vs. Pop Sensitivity

In the 1950s, the "Comics Code" and various censorship boards were very wary of anything that glorified crime. To get The Everly Brothers Take a Message to Mary on the radio, it had to be clear that the protagonist was suffering. He wasn't a hero; he was a cautionary tale. The song succeeded because it emphasized the emotional toll of his incarceration rather than the thrill of the "wrong turn" he took.

Chart Performance and Legacy

Surprisingly, "Take a Message to Mary" peaked at number 16 on the Billboard Hot 100. For many artists, that’s a career-high. For the Everly Brothers, it was almost a quiet success compared to their massive number-one hits. However, its longevity has been incredible. It’s been covered by everyone from Bob Dylan to Linda Ronstadt.

✨ Don't miss: Where to Find The Raid Redemption Streaming and Why It’s Still the King of Action

Dylan’s version, which appeared on his 1970 album Self Portrait, stripped away some of the polish and leaned into the folk-country roots of the melody. It proved that the song wasn't just a vehicle for sibling harmonies; it was a sturdy piece of songwriting that could hold up under different interpretations.

When you look at the discography of the Everlys, this track stands out as a precursor to the "outlaw country" movement that would take over a decade later. It showed that you could have a hit song about a convict without it being a "novelty" record or a rough-edged blues track.

Technical Brilliance in the Studio

Recording at RCA Studio B in Nashville was a specific experience. The room had a certain "slapback" echo that became synonymous with the Nashville Sound. For The Everly Brothers Take a Message to Mary, the engineer (often credited as Bill Porter, though sessions varied) had to balance the delicate acoustic guitars with that clinking screwdriver.

- Vocal Placement: Don and Phil usually sang into a single microphone to get that blended, "one voice" effect. In this session, the proximity was key. You can hear the breathiness.

- The Guitar Fill: The little walking guitar line between verses is classic Nashville. It’s simple, understated, and doesn't distract from the story.

- The Percussion: As mentioned, the Coke bottle/screwdriver combo was a stroke of DIY genius. It’s the kind of thing modern producers try to replicate with expensive plugins, but the original was just a guy hitting glass in a room.

The song is short—barely over two minutes. It doesn't overstay its welcome. It gives you the setup, the lie, and the heartbreaking realization that Mary is waiting for a guy who isn't coming home anytime soon.

💡 You might also like: Sunglasses at Night Corey Hart: What Most People Get Wrong

What Most People Get Wrong

A common misconception is that this song is a traditional folk ballad from the 1800s. It sounds so much like an old campfire song that people assume the Bryants just "arranged" it. That isn't true. It was a completely original composition written in the late 50s. The fact that it feels "timeless" is a testament to the Bryants' ability to tap into the American psyche.

Another mistake? Thinking the narrator is innocent. There is nothing in the lyrics to suggest he was framed. He admits he "went about it wrong." He owns the mistake, which actually makes the song more tragic. It’s not a protest song; it’s a regret song.

Final Insights for Music Enthusiasts

If you're looking to truly appreciate the depth of the Everly Brothers beyond their "teen idol" phase, "Take a Message to Mary" is the essential starting point. It’s a masterclass in narrative songwriting and minimalist production.

To get the most out of this track today:

- Listen for the "Prison Sound": Use a good pair of headphones and focus on the percussion. Once you hear that screwdriver hitting the bottle, you can't un-hear it. It changes the entire mood of the song.

- Compare the Harmonies: Listen to the 1959 original and then find a live version from their 1983 reunion concert at the Royal Albert Hall. Even decades later, the way their voices lock in on the word "Mary" is haunting.

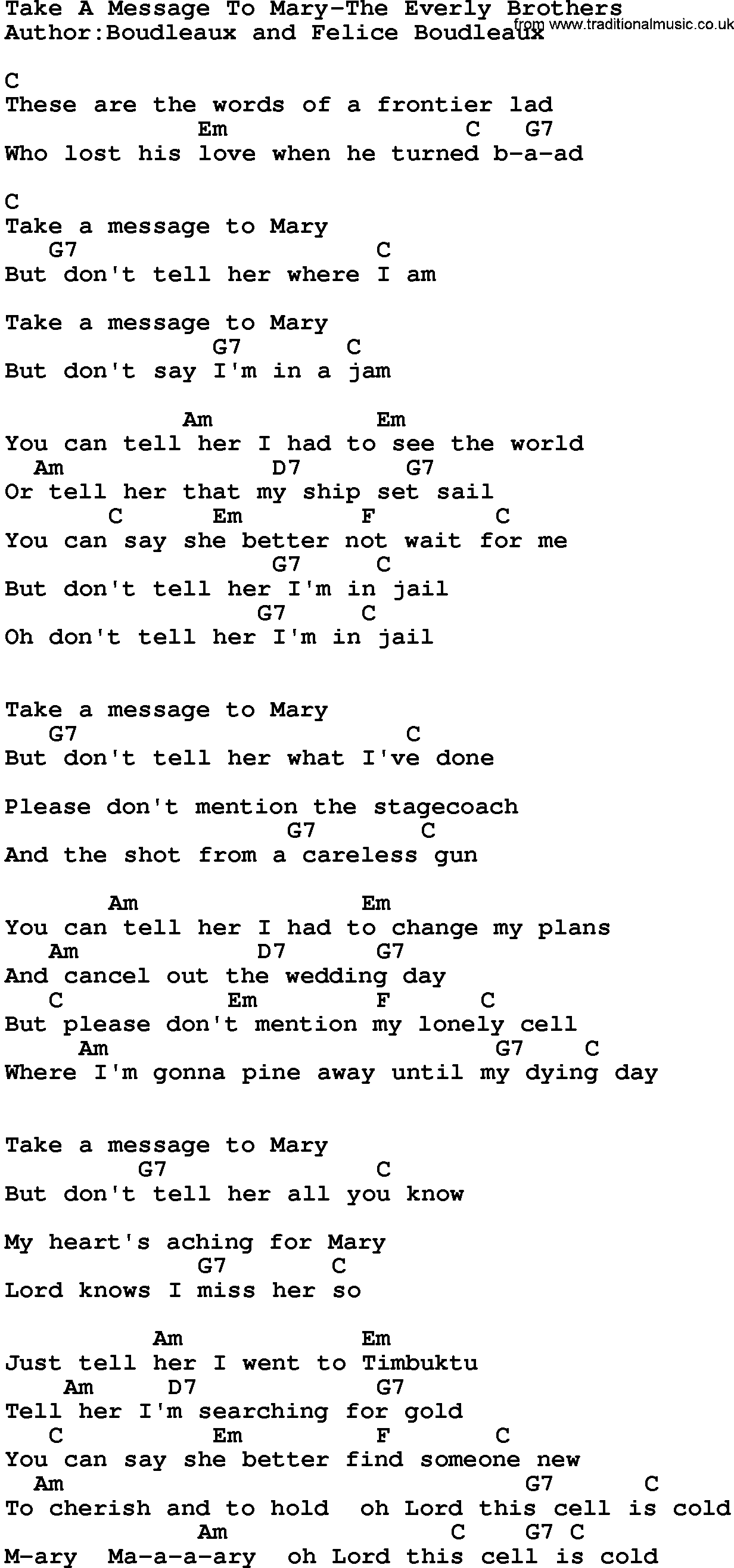

- Analyze the Lyrics as Poetry: Read the words without the music. It holds up as a short story. The economy of language—using "travelling" as a euphemism for "doing time"—is brilliant.

The Everly Brothers didn't just sing about holding hands. They sang about the messy, complicated, and sometimes dark realities of being human. That’s why, nearly seventy years later, we’re still talking about a message sent to a girl named Mary from a man who couldn't face her.

Check out the rest of the Cadence records era recordings to see how they pushed the boundaries of what a "pop" duo was allowed to do in the Eisenhower era. You’ll find that "Take a Message to Mary" wasn't an outlier; it was the moment they grew up.