You’ve probably seen the Pinterest-perfect loaves. Those crusty, rustic boules with the airy crumb and the deep, golden-brown exterior that looks like it belongs in a French bakery. You go out, buy the expensive organic bread flour, follow the hydration percentages to a T, and yet... it’s just okay. It lacks that soul. That nutty, complex, almost buttery aroma that fills the house and lingers on the tongue.

The missing link isn't your oven or your Dutch oven. It’s the grain. Or more specifically, how long ago that grain was crushed into powder.

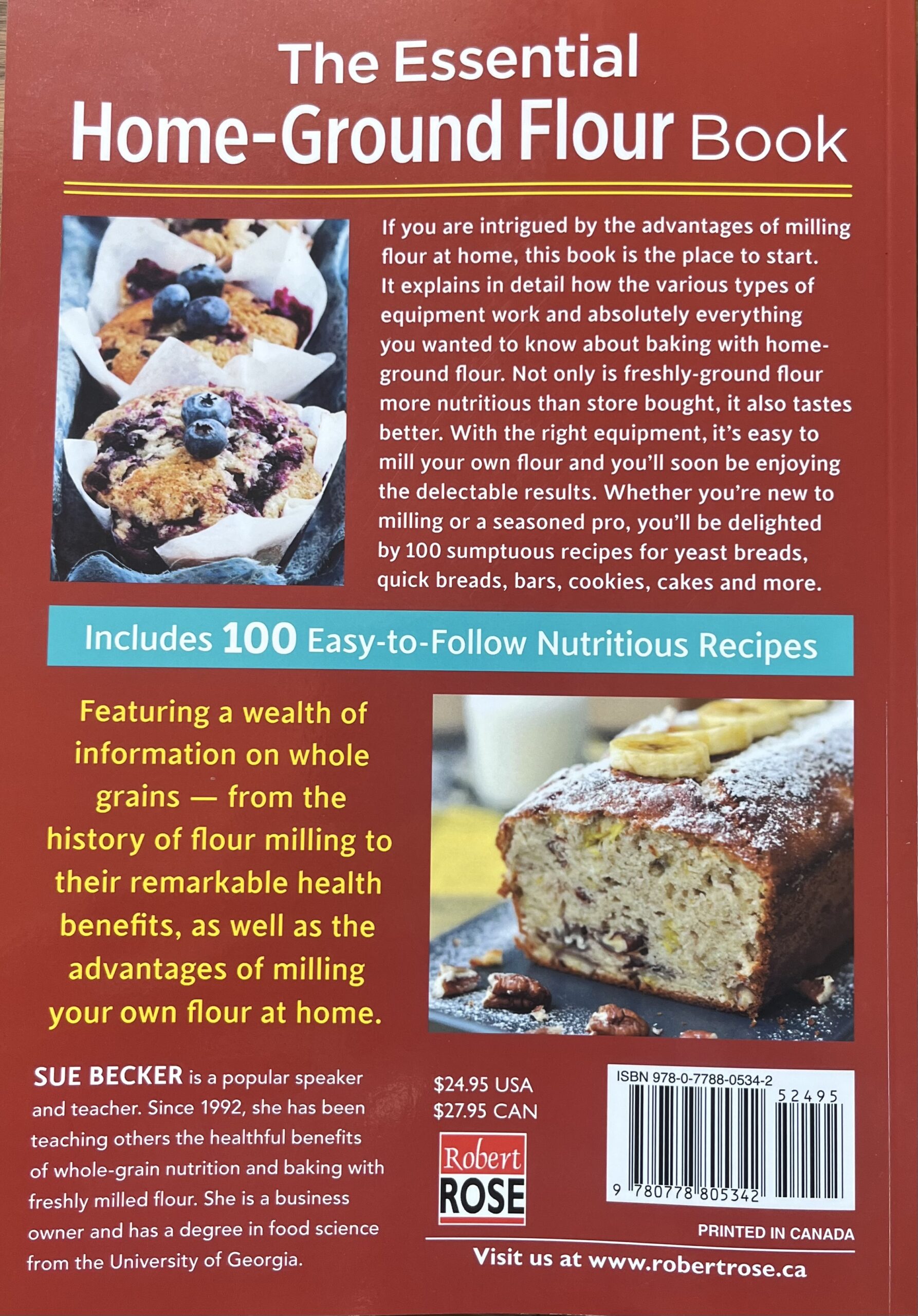

When people talk about The Essential Home Ground Flour Book by Sue Becker, they aren't just talking about another cookbook. Honestly, calling it a cookbook is kinda like calling a Ferrari just a car. It’s a manifesto. It’s the blueprint for anyone who has realized that the white powder sitting in a paper bag on a grocery store shelf for six months is essentially "dead" food. If you want to actually understand why your health or your sourdough hasn't reached the next level, you have to look at the chemistry of the kernel.

📖 Related: Buying a Couch Bed Full Size: Why Most People Choose the Wrong One

Freshness matters. A lot.

The Problem With Store-Bought "Whole Wheat"

Most people think buying "Whole Wheat" at the store is the healthy choice. It makes sense, right? It says whole grain on the label. But here is the dirty little secret of the industrial milling industry: they have to remove the germ.

The wheat kernel is made of three parts: the bran, the endosperm, and the germ. The germ is where the oils live. The minute you crack that kernel, those oils hit the oxygen in the air and start to go rancid. To make flour shelf-stable for months, commercial mills strip away the bran and germ, bleach the endosperm, and then "enrich" it with synthetic vitamins to replace what they just took out.

Sue Becker explains this beautifully in The Essential Home Ground Flour Book. She points out that within about 72 hours of milling, a huge percentage of the nutritional value—specifically the B vitamins and Vitamin E—is lost to oxidation. You’re eating a ghost of what the grain used to be.

When you mill at home, you get the whole thing. The oils are fresh. The flavor is intense. It’s the difference between a freshly squeezed orange and a carton of concentrate that’s been sitting in a warehouse.

Getting Started Without Losing Your Mind

If you’re diving into this world, the first thing you’ll notice is that there are way too many options. Impact mills? Stone burr mills? Manual cranks? It’s overwhelming.

Becker’s book is great because it doesn't just give you recipes; it explains the "why" behind the equipment. If you want a fine flour for delicate pastries or light sandwich bread, an impact mill like the NutriMill or the WonderMill is usually the go-to. They’re loud. Really loud. Like a jet engine in your kitchen. But they turn hard wheat berries into powder in seconds.

On the other hand, stone mills—like the Mockmill or the Komo—are the darlings of the artisan bread world. They crush the grain between two stones. This keeps the temperature lower, which some purists argue preserves even more nutrients. Plus, they look beautiful on a counter.

Whatever you choose, the realization is the same: the flour you make is different. It absorbs water differently. It rises differently. It smells like a field of grain, not a dusty attic.

The Learning Curve Is Real

Don't expect to just swap home-ground flour 1:1 into your favorite All-Purpose flour recipe and have it work perfectly. It won't. You’ll end up with a brick.

Freshly milled flour is "thirsty." The bran is still sharp and jagged because it hasn't been tempered or softened by industrial processes. Those little shards of bran act like tiny razor blades, cutting through the gluten strands as your bread rises. This is why many beginners get frustrated when their loaves don't double in size.

The Essential Home Ground Flour Book tackles this by teaching you about hydration and rest. You have to let the flour soak. This is often called an autolyse. By letting the flour and water sit for 20 to 30 minutes before you even add the yeast or salt, you give that bran time to soften up. It's a game-changer.

And let's talk about the varieties of wheat. Most people think "wheat is wheat." Wrong.

- Hard Red Wheat: High protein, strong gluten. This is your workhorse for yeast breads. It’s got a bold, "wheaty" flavor.

- Hard White Wheat: Still high protein, but milder. If you’re trying to trick your kids into eating whole grains, this is your secret weapon. It looks and tastes more like "white" bread but keeps all the nutrition.

- Soft Wheat: Low protein. This is for your biscuits, pie crusts, and muffins. If you try to make bread with this, it’ll be a sad, flat mess.

- Ancient Grains: Spelt, Einkorn, Kamut. These are the divas of the grain world. They’re finicky, they don’t like a lot of kneading, but the flavor is incredible. Einkorn, in particular, is the "original" wheat, and many people who have slight sensitivities to modern wheat find they can digest it much better.

Health Realities and the "Becker" Perspective

Sue Becker isn't just a baker; she has a background in food science, and she’s a huge advocate for the health benefits of real bread. In The Essential Home Ground Flour Book, she leans heavily into the idea that many modern "gluten sensitivities" might actually be sensitivities to the additives and the lack of fiber in processed flour.

She often cites the work of Dr. Sylvester Graham (yes, the Graham cracker guy) and other early 20th-century nutritionists who warned about the dangers of refined white flour. When you eat the whole grain, you get the fiber that slows down the absorption of sugar. You don't get the same insulin spikes. Your digestion actually works the way it's supposed to.

I’ve talked to people who started milling their own grain because of this book, and the stories are wild. People talk about their "brain fog" lifting or their chronic digestive issues disappearing. Is it a miracle cure? Probably not. Is it a massive improvement over the Standard American Diet? Absolutely.

Practical Tips for Your First Mill

Maybe you aren't ready to drop $500 on a high-end mill yet. That’s fair. It’s an investment.

But you can start small. You can actually find "wheat berries" at many health food stores or order them online from places like Palouse Brand or Azure Standard. If you have a high-powered blender like a Vitamix with a dry grains container, you can mill a small amount just to see the difference.

Just remember: only mill what you need. The whole point is freshness. If you mill five pounds of flour and stick it in the pantry for a month, you’ve defeated the purpose. You’re back to square one with oxidized oils.

When you get your copy of The Essential Home Ground Flour Book, flip straight to the section on "The Muffin Method." It’s one of the easiest ways to see the immediate impact of fresh flour without the stress of gluten development in yeast breads. A freshly milled blueberry muffin is a revelation. It’s not just a vehicle for sugar; the grain itself has a sweet, nutty profile that complements the fruit.

Beyond Just Bread

One thing that surprised me when I started down this rabbit hole was how much better everything tasted.

- Pancakes: They become fluffy but substantial.

- Gravy: Using a bit of freshly ground soft wheat for a roux adds a depth of flavor you can’t get from Gold Medal.

- Cookies: Chocolate chip cookies made with half-hard white wheat and half-soft wheat have a chewy, complex texture that makes the store-bought ones taste like plastic.

Becker’s book covers these bases too. It’s not just a "bread book." It’s a "how to feed your family" book. She includes recipes for everything from pizza dough to tortillas.

The Nuance of Sourdough

For the sourdough enthusiasts out there, fresh flour is like rocket fuel for your starter. Wild yeast loves the minerals found in the bran and germ of freshly milled grain. If your starter has been looking a little sluggish, feed it some freshly ground rye or whole wheat. It’ll practically crawl out of the jar.

However, be warned: fresh flour ferments fast. The enzymes are much more active. If you’re used to a 12-hour bulk fermentation in the fridge, you might find that your dough over-proofs much quicker with the home-ground stuff. You have to watch the dough, not the clock.

Actionable Next Steps for the Aspiring Miller

If this sounds like a lot, it is. But you don't have to do it all at once.

First, get the book. The Essential Home Ground Flour Book serves as a permanent reference guide. You’ll find yourself going back to the charts on grain types and troubleshooting long after you’ve mastered the basic recipes.

Next, find a source for your grain. Don't just buy the first bag you see. Look for "Non-GMO" and "un-bromated" labels. If you can find a local farmer, even better. The quality of the berry determines the quality of the flour.

Then, start with a "transition" loaf. Mix 25% freshly milled flour with 75% of your regular bread flour. See how it feels. See how it smells. Once you get a feel for the increased thirst of the dough, bump it up to 50%. Eventually, you might find you never want to touch the white stuff again.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a "red pill" moment. Once you taste real, fresh bread, the supermarket aisles start to look very different. You start to realize that we’ve traded nutrition and flavor for convenience and shelf-life. And once you know that, it's hard to go back.

Quick Checklist for Success:

- Invest in a scale. Volumetric measuring (cups) is too inaccurate for whole grains. A cup of freshly milled flour is much fluffier and lighter than a cup of packed store-bought flour. You will fail if you don't measure by weight in grams.

- Temperature control. If your mill runs hot, it can damage the flour. If you’re milling a lot at once, let the mill cool down or put your berries in the freezer for an hour before milling to keep the final flour temperature low.

- Store berries correctly. Whole wheat berries can stay fresh for years if kept in a cool, dry place in a sealed container. They are the ultimate survival food, but they are also the ultimate gourmet ingredient.

- Sift if you must. If you really want that light, airy texture for a cake but only have a grain mill, you can use a fine-mesh sieve to sift out the largest pieces of bran. You still get the fresh oils, but with a lighter texture.

The journey into home milling is a rabbit hole, for sure. But it’s one of the few kitchen upgrades that actually pays off in both health and flavor every single day.

Start by sourcing a small bag of Hard Red Spring Wheat and a simple manual or electric mill. Focus on mastering one simple sandwich bread recipe from the book before moving on to complex sourdoughs. Take notes on the hydration levels—write down exactly how many milliliters of water you added and how the dough felt. Over time, you'll develop a "feel" for the grain that no machine can replicate. This isn't just about baking; it's about reclaiming a lost art of nourishment.