May 18, 1980, started out as a gorgeous Sunday morning in Washington State. It was quiet. Most people were just waking up, maybe grabbing a coffee or looking at the clear blue sky. But at 8:32 a.m., the world basically ripped open. The eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980 wasn't just a volcano blowing its top; it was a total geographical lobotomy that changed how we look at the Earth forever. Honestly, if you weren't there, it’s hard to grasp the sheer scale of the mess it made.

We’re talking about a mountain that lost 1,300 feet of its summit in seconds.

The energy released? It was roughly equivalent to 1,600 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs. That’s not a typo. It was massive, violent, and frankly, a bit terrifying for the geologists who had been watching it for weeks. They knew something was coming, but nobody—absolutely nobody—predicted the mountain would fall over sideways.

The Lateral Blast That Nobody Saw Coming

For months, the north face of the mountain had been bulging. It was growing by about five feet a day. Geologists like David Johnston were stationed nearby, keeping a close eye on the "bulge." Most people expected a vertical eruption, the kind you see in school textbooks where the smoke goes straight up like a chimney.

That’s not what happened.

When a 5.1 magnitude earthquake hit that morning, the entire north side of the peak just... slid away. It was the largest debris avalanche in recorded history. With the weight of the rock gone, the super-heated gas and magma inside the mountain didn't have anything holding it back anymore. It exploded horizontally.

This lateral blast moved at 300 miles per hour. Maybe faster. It didn't care what was in the way. It flattened 230 square miles of ancient forest like they were toothpicks. If you look at photos of the "Blowdown Zone" today, you can still see the trees lying in perfect rows, all pointing away from the crater. It’s a haunting reminder of the direction the wind—if you can call a wall of 600-degree ash "wind"—was blowing that day.

✨ Don't miss: Hotel Gigi San Diego: Why This New Gaslamp Spot Is Actually Different

The Human Cost and the Spirit Lake Legend

57 people died. That number feels small given the scale of the destruction, but each story is a gut punch. You’ve probably heard of Harry R. Truman. He was the 83-year-old guy who refused to leave his lodge at Spirit Lake. He’d lived there for 50 years and basically told the authorities to kick rocks. He, his lodge, and his 16 cats were buried under hundreds of feet of debris within minutes.

Then there was David Johnston, the young USGS volcanologist. He was on a ridge about six miles away. His last words over the radio were, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" He was gone seconds later.

It’s easy to look back and say people should have evacuated further, but the "red zone" established by the government was actually quite small. Many of the people who died were technically in "safe" areas. The mountain just didn't play by the rules. It didn't help that it was a weekend, and logging crews weren't in the woods; otherwise, the death toll could have been in the hundreds or even thousands.

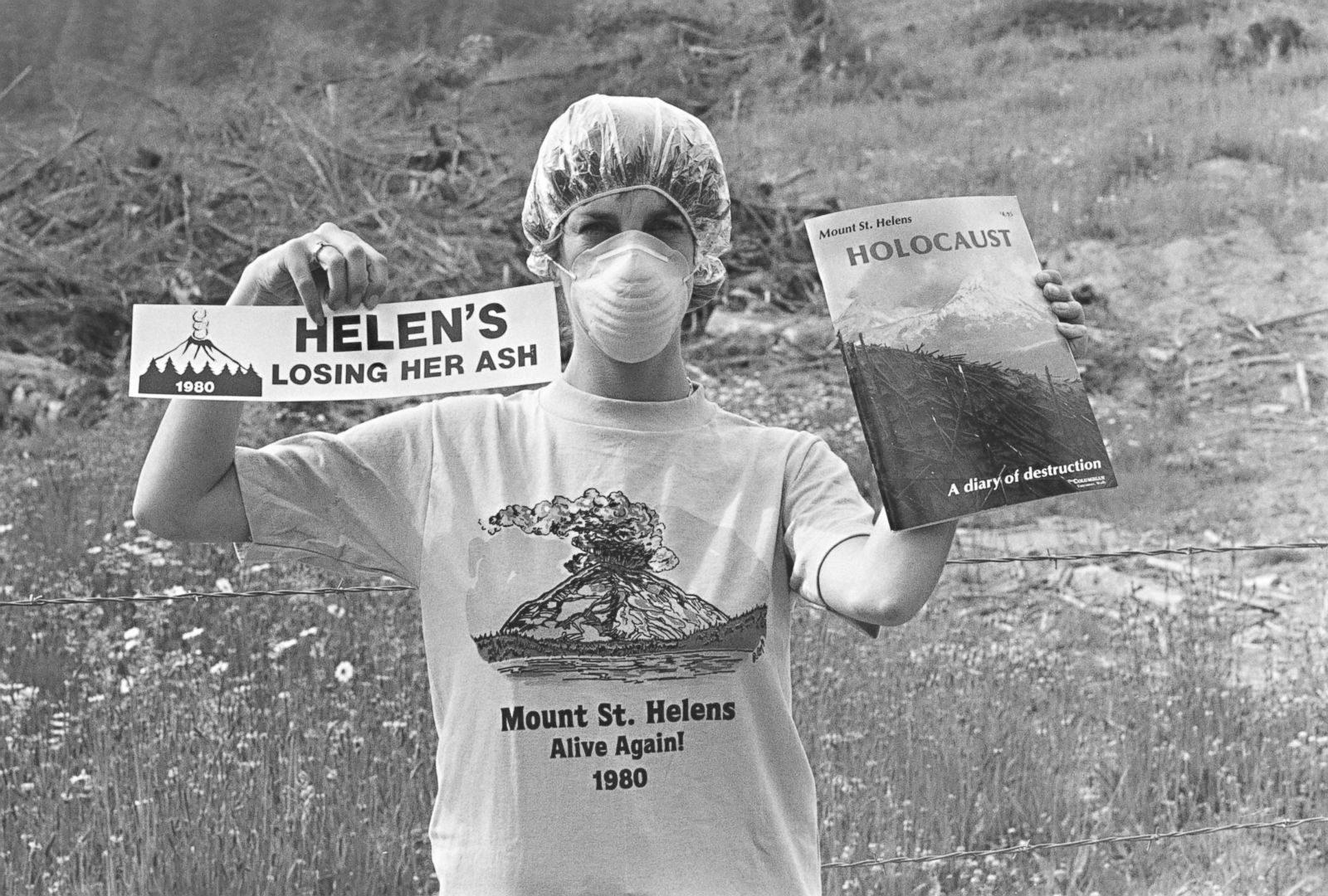

Ash: The Gritty Reality of the Aftermath

If you lived in Yakima or Spokane in May 1980, your world turned pitch black in the middle of the day. The ash cloud rose 80,000 feet into the atmosphere in less than 15 minutes. It stayed dark for hours.

People describe the ash as feeling like pulverized glass. Because, well, it was. It wasn't soft like wood ash from a fireplace. It was heavy, abrasive, and it wrecked everything.

- Car engines seized because the ash acted like sandpaper on the pistons.

- Sewage systems clogged up.

- The weight of the damp ash collapsed roofs.

- Even in Idaho and Montana, people were wearing surgical masks just to breathe.

Total chaos.

🔗 Read more: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the 1980 Eruption Changed Science Forever

Before the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, volcanology was a bit more guesswork than we’d like to admit. This event was a wake-up call. It led to the creation of the Cascades Volcano Observatory. Scientists realized they needed better ways to monitor seismic activity and gas emissions.

We also learned about "lahars." These are massive volcanic mudslides that happen when the heat of an eruption melts snow and glaciers instantly. The lahars from St. Helens turned the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers into slurries of concrete-like mud. They carried houses, trucks, and bridges miles downstream. Now, we have sensors on mountains like Mt. Rainier specifically to detect these mudflows before they hit populated valleys.

Nature’s Weird Way of Bouncing Back

You’d think a 600-degree blast would sterilize the earth forever. Sorta looks that way in the old footage. But life is stubborn.

Gophers actually saved the day in many areas. Because they live underground, many survived the heat. When they started digging back up, they brought fresh, un-ashed soil to the surface. This soil contained seeds and fungi that helped the forest start over. Then there were the "prairie lupines," the first flowers to pop up in the gray wasteland. They could fix nitrogen in the soil, making it possible for other plants to grow.

If you visit the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument now, it’s green. It’s not the same forest it was—it’s younger, scrubbier—but it’s alive. The blast zone is a massive, outdoor laboratory.

Common Misconceptions About the Big Day

A lot of people think the mountain is "done." It’s not. It erupted again as recently as 2004 to 2008, building a new lava dome inside the crater. It’s still one of the most active volcanoes in the United States.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

Another myth is that the eruption was a total surprise. The USGS had been issuing warnings for weeks. The problem was the type of eruption. Everyone was looking at the top; nobody was looking at the side.

And no, you couldn't see the "smoke" from California. You could, however, see the ash cloud from space, and the pressure wave from the blast was heard as far away as British Columbia. Interestingly, people living right next to the mountain often heard nothing. It’s called an "acoustic shadow." The sound skipped right over the immediate area and landed hundreds of miles away.

Planning a Visit to the Blast Zone

If you’re heading out to see the site of the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, don't just stick to the main highway.

- Johnston Ridge Observatory: This is the closest you can get to the crater without a hiking permit. You’re standing right where David Johnston was. The view of the "crater mouth" is staggering.

- Ape Cave: On the south side of the mountain, you can walk through a literal lava tube from a much older eruption. It stayed mostly intact during 1980.

- The Hummocks Trail: You’ll walk through the actual chunks of the mountain that fell off during the landslide. It’s weirdly hilly terrain created by disaster.

- Spirit Lake Highway: Keep an eye out for the "buried A-frame" house. It's a stark visual of how deep the mud was.

Check the Gifford Pinchot National Forest website before you go. Road washouts are common because the soil is still unstable in some spots. Also, the weather at the mountain is nothing like the weather in Seattle or Portland. It can be sunny in the city and a total whiteout at the ridge.

Actionable Insights for the Future

The 1980 event wasn't a one-off. The Cascade Range is a "string of pearls" of volcanoes, including Rainier, Hood, and Shasta.

- Look at Hazard Maps: If you live in the Pacific Northwest, find out if you’re in a lahar zone. Most people in towns like Orting, WA, are living on top of old volcanic mudflows.

- Keep an Emergency Kit: This isn't just for "preppers." Ashfall can happen again. Have N95 masks and extra air filters for your car and home.

- Support Monitoring: Volcanic monitoring is often the first thing to get budget cuts. Scientific funding for the USGS is what gives us the weeks of warning we need to get people out of the way.

The mountain is a lot smaller now, but it's just as powerful. Standing on the edge of that crater, you realize humans are basically just ants on a very large, very grumpy ant hill. We don't control the Earth; we just live here during the quiet parts.

To get the most out of your trip to the monument, start at the Mount St. Helens Visitor Center at Silver Lake to get the timeline straight. Then, drive up to the higher elevations to see the scale of the recovery. Seeing the "ghost logs" still floating in Spirit Lake is something you won't forget anytime soon. It’s a literal time capsule of May 18, 1980.