Imagine trying to download the entire internet onto paper in the middle of a country where the king can throw you in a dungeon for a bad tweet. That’s basically what Denis Diderot did. He didn't just want to make a big dictionary. He wanted to change the way people think. It was dangerous. It was messy. It almost failed a dozen times.

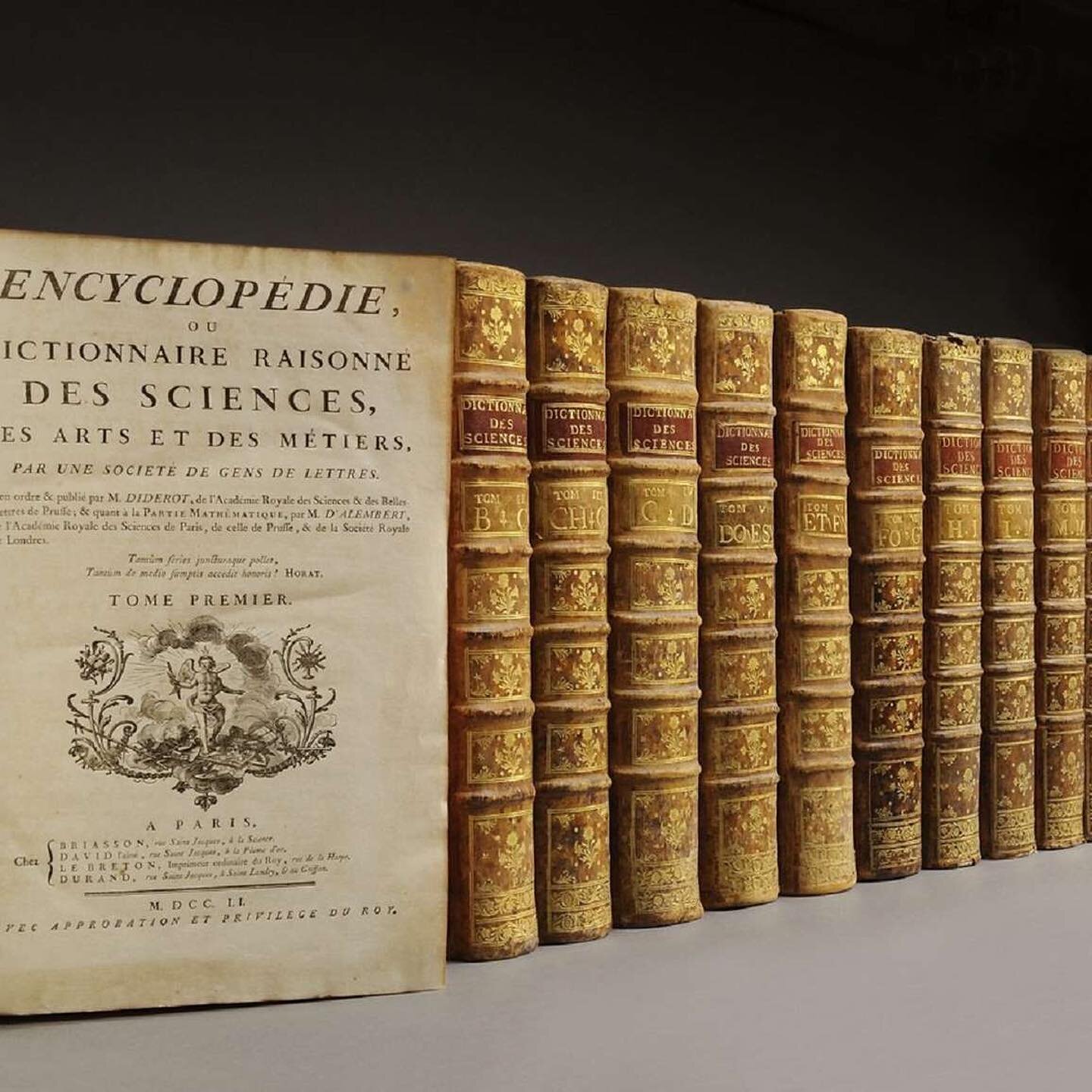

The Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers is the full, exhausting title of the project we now just call Diderot and the Encyclopedia. It’s the DNA of the modern world. Before this, knowledge was a secret kept by priests and kings. After this? Knowledge belonged to anyone who could read.

The Man Behind the Madness

Denis Diderot wasn't some stuffy academic living in a ivory tower. He was a caffeine-addict, a playwright, and a bit of a rebel who spent time in prison for writing things the church didn't like. He was broke. He was brilliant. When a publisher approached him to just translate an English encyclopedia called Cyclopaedia by Ephraim Chambers, Diderot had a bigger, much crazier idea. He wanted to document everything. Every trade. Every scientific discovery. Every philosophical debate.

He teamed up with Jean le Rond d'Alembert, a mathematical genius, and they started recruiting the "Philosophes." Think of them as the original Avengers of the Enlightenment. Voltaire was involved. Rousseau was there, at least until he and Diderot had a massive falling out because, honestly, Rousseau was hard to get along with.

The War on Ignorance

The project was massive. We're talking 28 volumes, 71,818 articles, and 3,129 illustrations. It took over 20 years to finish. But the numbers don't tell the real story. The real story is the subversion. Diderot knew the censors were watching him. If he wrote an article called "Why the King is Wrong," he’d be executed. So, he got sneaky.

He used a "cross-reference" system that was basically the 18th-century version of a hyperlink. You’d read a very respectful, safe article about "Cannibalism," and at the end, it might say See also: Eucharist. That is top-tier trolling. It forced the reader to make their own connections. It taught people to question authority without Diderot having to say it directly.

🔗 Read more: Dating for 5 Years: Why the Five-Year Itch is Real (and How to Fix It)

Why Diderot and the Encyclopedia Changed Everything

Before this book, if you wanted to know how to build a printing press or weave silk, you had to be part of a guild. These were secret societies. They kept their methods hidden to keep prices high. Diderot hated that. He believed that "the man of the world" should understand the "man of the shop."

He spent days in workshops. He interviewed blacksmiths. He watched weavers until his eyes hurt. He insisted on including massive, detailed copperplate engravings of machines. Why? Because he believed that manual labor was just as noble as philosophy. This was a radical, almost "lifestyle" shift for the elites. Suddenly, a Duke was reading about how to tan leather. The "arts and crafts" (the métiers) were finally being treated with the same respect as theology.

The Censorship Battles

The French government hated it. The Pope hated it. In 1752, the King’s Council suppressed the first two volumes. They said it was "trying to destroy royal authority and establish the spirit of independence." They weren't wrong.

In 1759, the project’s license was revoked. D'Alembert quit because he couldn't handle the stress. Diderot stayed. He worked in secret. He hid the manuscripts in the houses of sympathetic nobles—even the Director of the Book Trade, Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, helped hide the pages from the very police he was supposed to be leading. It’s one of the great ironies of history.

The Physicality of Knowledge

Have you ever actually looked at the plates from the Encyclopedia? They are gorgeous. They didn't just show a tool; they showed the tool in motion. They showed the human hand interacting with the world.

💡 You might also like: Creative and Meaningful Will You Be My Maid of Honour Ideas That Actually Feel Personal

Diderot's goal was to make knowledge "useful." He wasn't interested in abstract nonsense that didn't help a person live a better life. This is why Diderot and the Encyclopedia is often cited as the catalyst for the Industrial Revolution. By standardizing technical language and sharing "secret" methods, he lowered the barrier to entry for innovation.

A Complicated Legacy

We have to be honest: Diderot wasn't perfect. By 2026 standards, some of the entries on race or gender in the Encyclopedia are cringeworthy or outright offensive. He was a man of his time. But the process he started—the idea that we should collect, verify, and democratize information—is what led us to Wikipedia and the very screen you're reading this on.

He struggled with the sheer scale of it. He often complained that the work was killing him. He felt like a slave to the alphabet. Yet, he pushed through because he believed that "posterity" would thank him. He was right.

How the Encyclopedia Still Impacts Your Life

You might think an old French book has nothing to do with your 9-to-5 or your weekend hobbies. You’d be surprised.

- The Idea of the "Generalist": Diderot championed the idea that a person should know a little bit about everything. This is the foundation of a liberal arts education.

- Information Design: The way we use diagrams and "how-to" guides stems directly from the visual style of the Encyclopedia’s plates.

- Public Access: The concept that a library should be a place for the public to learn, not just a vault for the elite, was solidified by the Enlightenment's push for shared knowledge.

The Encyclopedia wasn't just a book. It was a weapon. It was a tool designed to "change the common mode of thinking." It taught a generation of French citizens that they didn't just have to obey; they could understand. And once you understand how the world works, it’s very hard to let someone else tell you how to live in it.

📖 Related: Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Waldorf: What Most People Get Wrong About This Local Staple

Actionable Insights from Diderot’s Methodology

If you want to apply the spirit of Diderot and the Encyclopedia to your own life or business, start here:

- Document your processes. Diderot knew that "tacit knowledge" (stuff people know but don't write down) dies with the individual. Whether it's a family recipe or a workflow at your office, write it down. Make it accessible.

- Cross-pollinate your interests. Don't just stay in your niche. If you're a coder, read about woodworking. If you're an artist, study biology. The "cross-reference" is where the most creative ideas happen.

- Value the "How" as much as the "Why." Don't look down on practical skills. Understanding the mechanics of your world—how your car works, how your food is grown, how your computer processes data—gives you a level of independence that purely theoretical knowledge cannot.

- Practice "Skeptical Reading." Just as Diderot used cross-references to bypass the censors, modern readers must look for the "hidden" context in what they consume. Don't take any single source as the absolute truth.

- Build a "Knowledge Common." Share what you know for free. Whether it's through a blog, a community workshop, or mentoring, the democratization of information is the best way to ensure progress and prevent the concentration of power in too few hands.

The work of Diderot reminds us that facts aren't just data points. They are the building blocks of freedom. When we stop caring about the accuracy and accessibility of information, we move backward toward the very dark ages Diderot fought so hard to leave behind.

To truly understand the Enlightenment, one must look at the ink-stained fingers of the man who refused to stop writing, even when the world told him to be quiet. Diderot's life work proves that a single project, born from a humble translation job, can eventually topple thrones and redefine the human experience.

Source References:

- The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800 by Robert Darnton.

- Diderot: The Art of Thinking Freely by Andrew S. Curran.

- The Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert: Selected Articles (University of Michigan Library translation project).