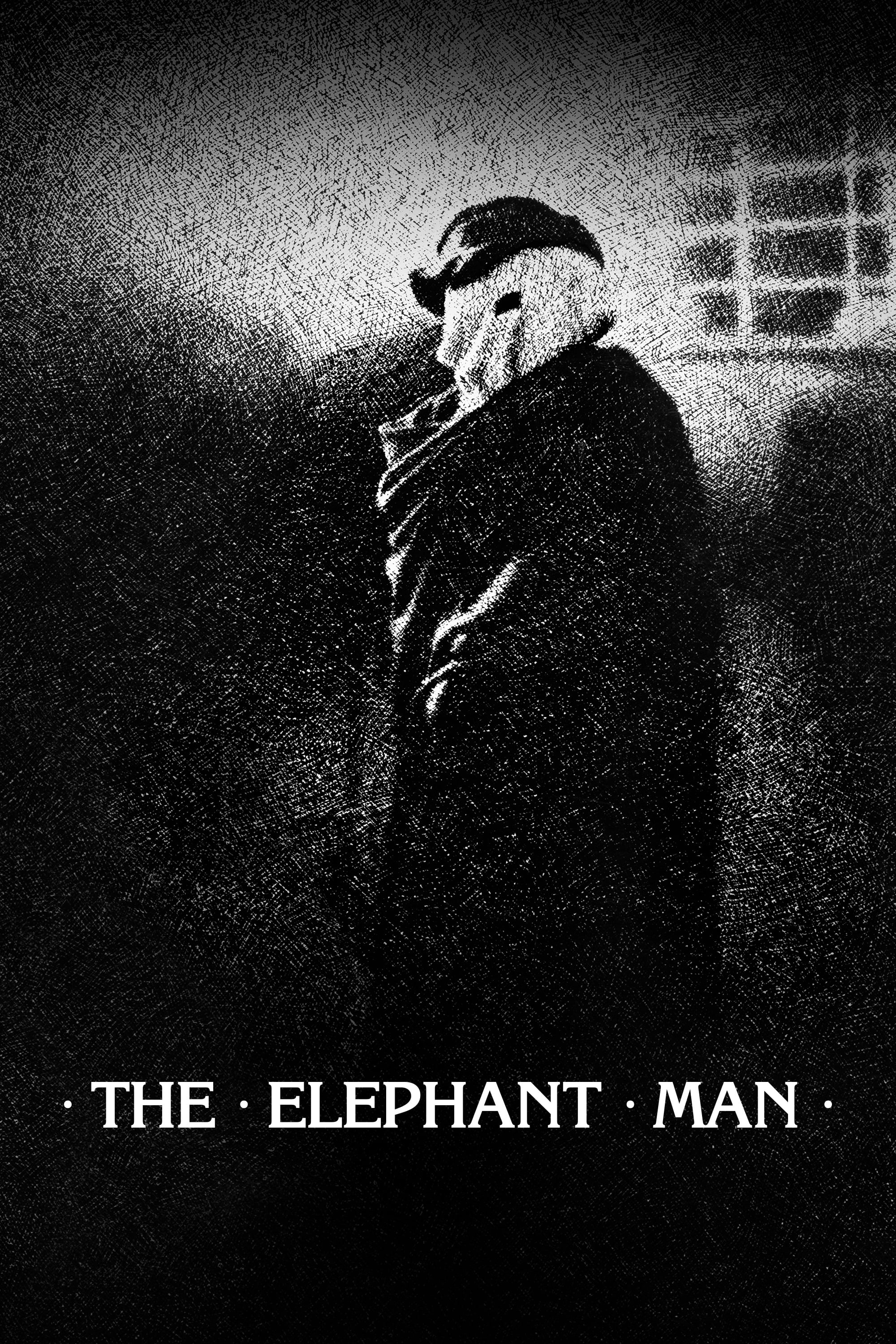

If you’ve ever sat through a movie and felt like your chest was being stepped on, you probably know the feeling of watching The Elephant Man. It’s not just a "sad movie." Honestly, calling it sad feels like a massive understatement. Released in 1980, this black-and-white fever dream from David Lynch managed to do something most biopics fail at: it captured the soul of a man buried under a mountain of physical deformity without making him a caricature.

John Merrick—based on the real-life Joseph Merrick—is a name that carries a lot of weight.

Most people think they know the story. A man with severe physical deformities is rescued from a Victorian freak show by a kind doctor, finds his humanity, and then dies. But the movie is way more complex than that. It’s about the voyeurism of the "civilized" world. It’s about how we look at people who don't look like us.

Lynch took a massive risk here. Before this, he was the guy who made Eraserhead, a movie so weird it basically defined "cult film." Then, suddenly, he's directing a prestige period piece produced by Mel Brooks. Yeah, that Mel Brooks. Brooks actually kept his name off the credits as a producer because he didn't want audiences to think it was a comedy.

The Real Joseph Merrick vs. The Movie Elephant Man

First off, let's clear up a bit of history because the movie takes some liberties. In the film, he’s John. In real life, his name was Joseph. Why the name change? It’s likely because the source material Lynch used—Sir Frederick Treves' own memoirs—got the name wrong. Treves was the surgeon who "discovered" Merrick, and for whatever reason, he remembered him as John.

History is funny like that.

The real Joseph Merrick wasn't actually rescued from a life of pure misery in the way the film suggests. Don't get me wrong, it wasn't great. But historical records suggest he actually entered the freak show business somewhat willingly at first because it was his only alternative to the workhouse. In Victorian England, if you couldn't work a physical job, you were basically left to rot. Merrick was smart. He knew his body was a "commodity."

The movie paints Tom Norman—the showman—as a villain. In reality, Norman and Merrick supposedly had a professional relationship that was a bit more nuanced. But for the sake of a two-hour runtime, you need a bad guy.

What exactly was his condition?

For decades, people thought Merrick had neurofibromatosis. That was the go-to medical explanation for a long time. However, in the late 70s and early 80s, doctors started leaning toward Proteus syndrome. It’s incredibly rare. We’re talking "one in a million" rare. It causes an overgrowth of bones, skin, and other tissues.

If you look at the actual photos of Merrick’s skeleton, which is still preserved at the Royal London Hospital, the physical reality is staggering. His skull was massive. His right arm was overgrown to the point of being useless. Yet, his left hand? It was described as delicate, almost feminine. That contrast is a huge part of why the movie hits so hard.

Why John Hurt’s Performance Is Legendary

You can't talk about The Elephant Man without talking about John Hurt. He spent seven to eight hours in the makeup chair every single day. Seven hours. Just to get into character.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

He couldn't eat normally while in the makeup. He had to be at the studio at 5:00 AM.

The makeup was designed directly from casts of Joseph Merrick’s body. It wasn't some Hollywood "interpretation" of what deformity looks like; it was a recreation. Hurt’s performance is a masterclass because he has to act through inches of foam and latex. He does it with his voice. He does it with the way he tilts his head.

There's that famous scene. You know the one. He’s cornered in the train station by a mob of people who are treating him like an animal. He screams, "I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being! I... am... a man!"

It’s iconic. It’s the emotional peak of the film.

But here’s the thing: John Hurt almost didn't do it. He once joked that the producers had found a way to make him hate acting. But that physical suffering he went through? It translates. You can feel the exhaustion in Merrick’s bones.

The Beauty of the Black and White Aesthetic

Why did David Lynch choose to shoot in black and white? It wasn't just to be "artsy."

- The Victorian Vibe: London in the 1880s was soot-stained, foggy, and grim. Black and white captures that industrial grime perfectly.

- The Makeup: Even with the incredible work of Christopher Tucker, color film can sometimes make prosthetics look... well, like prosthetics. Black and white blends the edges. It makes the shadows work for the story.

- The Dreamscape: Lynch loves the "in-between" spaces. The opening of the movie, with the elephants and the slow-motion dream sequence, feels like a nightmare. It sets the tone that this isn't a standard biopic.

Freddie Francis, the cinematographer, did an incredible job. He used Panavision cameras to give it a wide, cinematic feel that makes Merrick look even smaller and more isolated in those big, cold hospital rooms.

Anthony Hopkins and the Moral Gray Area

Anthony Hopkins plays Frederick Treves. He’s the "hero," right? He brings Merrick to the hospital. He gives him a room. He introduces him to high society.

But Lynch is smarter than your average director. He lets the movie ask a very uncomfortable question: Is Treves actually any better than the freak show manager?

There’s a moment where Treves realizes he’s basically just putting Merrick on display for a "better" class of people. Instead of a tent in a dark alley, it’s a brightly lit operating theater for medical students. Instead of drunks paying a penny, it’s countesses and dukes bringing gifts.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Is it still a cage if the bars are made of gold?

Hopkins plays this internal conflict perfectly. You see the guilt on his face when he realizes that Merrick is actually a highly intelligent, sensitive, and deeply religious man who reads poetry and builds models of cathedrals.

The Sound Design: The Secret Weapon

If you close your eyes and listen to The Elephant Man, it sounds like a factory.

There is a constant, low-level industrial hum. Steam hissing. Rhythmic thumping. It’s the sound of the Industrial Revolution devouring the human spirit. Lynch is a sound design nerd (he often does his own), and he uses audio to create a sense of impending doom.

Even when Merrick is safe in his room, you can hear the machines outside. It reminds the audience that the world is a cold, mechanical place that doesn't have room for someone as "irregular" as Joseph.

The score, by John Morris, is also heartbreaking. That main theme—the "Adagio for Strings" by Samuel Barber used at the end—is basically a cheat code for making an entire audience weep. Interestingly, Lynch used the Barber piece as a temp track during editing and liked it so much he kept it, even though it wasn't original to the film.

What the Movie Gets Right About Human Dignity

The core of this film isn't about being "deformed." It's about the basic human need to be seen.

There is a scene where Merrick meets Treves' wife. She treats him like a gentleman. She offers him tea. She looks him in the eye and smiles. Merrick starts to cry. He says he’s not used to being treated with such kindness by a "beautiful woman."

It’s a simple scene. No big speeches. No explosions. Just three people having tea. But in the context of Merrick's life, it’s a miracle.

The film also explores the idea of "normality." Merrick’s greatest wish isn't to be "cured." He knows he can't be. He just wants to sleep like a "normal" person. Because of the weight of his head, he had to sleep sitting up. If he laid down, the weight would crush his windpipe.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

The ending—where he finally decides to lie down—is both beautiful and devastating. It’s an act of agency. He chooses how he wants his story to end.

Common Misconceptions About the Movie

People often get a few things mixed up when they talk about this film:

- "It's a horror movie." No. It’s a drama with some surrealist elements. Just because David Lynch directed it doesn't mean there's a guy behind a dumpster or a lady in the radiator (though the opening is definitely creepy).

- "The movie says he had elephantiasis." Actually, the term "Elephant Man" was just a stage name. The movie doesn't spend much time on a specific diagnosis, focusing instead on the social impact.

- "Merrick was mentally disabled." This was a huge misconception in the 19th century that the movie works hard to debunk. Merrick was incredibly articulate and literate.

Critical Legacy and Awards

This movie was so impactful that it actually caused the Academy Awards to create a new category. In 1980, there was no Oscar for "Best Makeup." When the Academy refused to give Christopher Tucker a special award for his work on John Hurt, the industry was outraged.

The next year, the "Best Makeup and Hairstyling" category was officially added.

The film was nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor. It didn't win any. Not one. It lost Best Picture to Ordinary People. Looking back, many critics feel The Elephant Man has aged significantly better than some of the other winners from that era.

How to Watch It Today

If you’re going to watch it, try to find the 4K restoration by the Criterion Collection. The contrast is much sharper, and you can see the incredible detail in the makeup and the set design.

Don't watch it while you’re already feeling down. It’s a heavy lift. But it’s also one of those movies that makes you feel more human after you've seen it.

Actionable Takeaways for Film Buffs and History Fans

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Joseph Merrick, here are a few things you should actually do:

- Read the original memoirs: Look for The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences by Sir Frederick Treves. It’s fascinating to see how the doctor viewed Merrick in his own words.

- Visit the Royal London Hospital Museum: They have a small exhibit dedicated to Merrick, including replicas of his hat and mask. It puts the "character" back into a real-world perspective.

- Compare it to the stage play: There is a famous play by Bernard Pomerance about Merrick. Interestingly, the play usually features an actor with no makeup, using body contortion to suggest the deformity. It’s a completely different experience than the movie.

- Check out Lynch’s other "accessible" work: If you liked the tone of this, watch The Straight Story. It’s another G-rated (yes, really) movie by Lynch that is surprisingly moving and human.

The story of the Elephant Man isn't just a Victorian curiosity. It's a mirror. When we look at Merrick, we aren't just seeing his deformities; we're seeing the reaction of everyone around him. And that's usually where the real horror—and the real beauty—lies.