It’s easy to look back at the American Civil War as an inevitable victory for the North. We see the photos of a stoic Abraham Lincoln, we read the Gettysburg Address, and we assume the Union was always going to hold. But by the summer of 1864, the vibe in the North was basically pure despair. The war had been dragging on for three agonizing years. Bodies were piling up in numbers that no one had ever seen before. People were tired. Honestly, they were beyond tired—they were broken.

The election of 1864 wasn't just a political contest; it was a referendum on whether the United States should even continue to exist as a single nation. No country had ever tried to hold a high-stakes national election in the middle of a bloody civil war. It was risky. Some of Lincoln's own advisors told him to postpone it. They thought he’d lose. Lincoln himself thought he’d lose. He actually wrote a "blind memorandum" in August, asking his cabinet to pledge to save the Union between the election and the inauguration because he was that certain George McClellan would beat him.

The General vs. The President

The setup was weird. You had Abraham Lincoln, representing the newly formed National Union Party (a temporary merger of Republicans and War Democrats), running against his own former top general, George B. McClellan.

McCllellan is a fascinating, frustrating figure in history. Lincoln had fired him—twice. McClellan was popular with the soldiers, but he was cautious to a fault. He had the "slows," as Lincoln put it. Now, he was the face of the Democratic Party, which was deeply split. The "Peace Democrats," or Copperheads, wanted an immediate end to the war through a negotiated settlement. They basically wanted to call it quits and let the South go.

McClellan was in a tough spot. He was a "War Democrat," meaning he wanted to keep fighting to restore the Union, but his party’s platform was written by the peace faction. It called the war a failure. Imagine running for President on a platform that says the thing you spent the last three years doing—leading an army—was a complete waste of time. That’s a tough sell.

Why 1864 was a Total Mess

The casualty counts were horrific. In the spring of 1864, Ulysses S. Grant launched the Overland Campaign. In just six weeks, the Union suffered about 55,000 casualties. For context, that’s nearly as many as the U.S. lost in the entire Vietnam War. The public was horrified. They started calling Grant a "butcher."

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

If you were a voter in July 1864, you saw:

- A stalemate in Virginia.

- Gold prices skyrocketing because of war inflation.

- Draft riots in major cities.

- Constant funerals.

The narrative was that Lincoln was an incompetent radical who was destroying the country for a cause—abolition—that many Northern voters were still skeptical about. Remember, the Emancipation Proclamation had changed the stakes. It wasn't just about "The Union" anymore; it was about ending slavery. For a lot of white Northerners in the 1860s, that was a bridge too far.

The "October Surprise" of the 19th Century

Everything changed in September. If the election of 1864 had happened in August, Lincoln almost certainly loses. But then, William Tecumseh Sherman took Atlanta.

This was massive. Atlanta was a major Confederate hub. Its fall proved that the North was actually winning. It wasn't a "failure" like the Democratic platform claimed. Shortly after, Admiral David Farragut won the Battle of Mobile Bay, and Philip Sheridan cleared the Confederates out of the Shenandoah Valley. Suddenly, the "peace at any price" argument looked ridiculous.

The mood shifted overnight. Winning is the best campaign strategy ever invented.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

The Soldier Vote

One of the most incredible parts of the election of 1864 was the fact that the soldiers got to vote. This was revolutionary. Most states passed laws allowing men in the field to cast ballots.

Think about the psychology there. These men were living in trenches, eating hardtack, and watching their friends die. You’d think they would want the war to end more than anyone. You’d think they’d vote for McClellan, the guy who promised to stop the bleeding.

They didn't.

They voted for Lincoln by a landslide. About 78% of the soldier vote went to "Old Abe." They wanted to finish the job. They felt that a negotiated peace would mean their brothers-in-arms had died for nothing. It’s one of the most powerful examples of "voting with your boots" in history.

The Results and the Aftermath

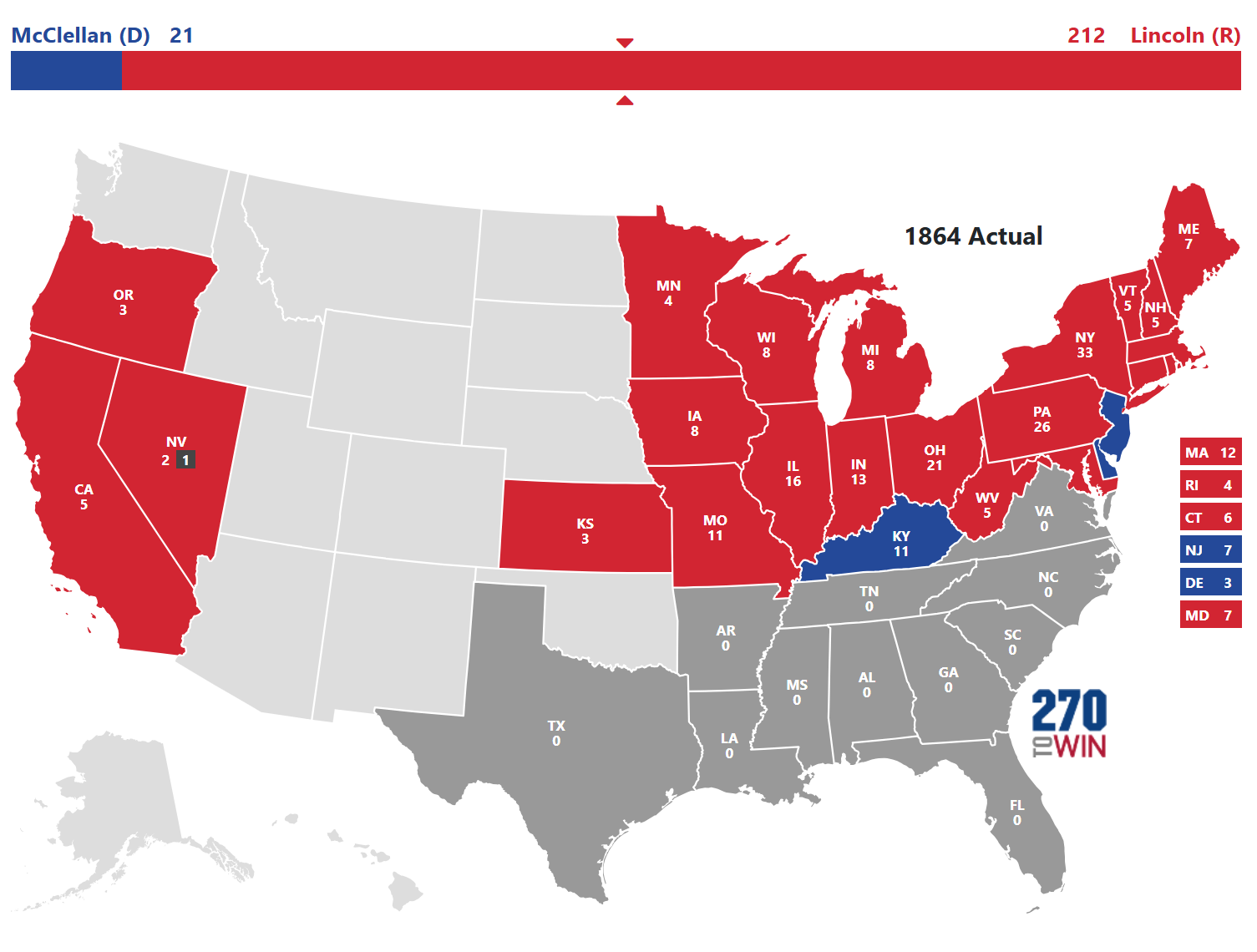

Lincoln ended up winning 212 electoral votes to McClellan’s 21. It looks like a blowout on paper, but the popular vote was closer—about 55% to 45%. A lot of people still wanted out.

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

By winning, Lincoln got a mandate to push for the 13th Amendment. He knew that if he didn't codify the end of slavery while the war was still going, it might never happen. The election of 1864 ensured that the United States would emerge from the war as a completely different nation, not just a restored version of the old one.

What We Get Wrong About 1864

Most people think the North was a monolith of "save the Union" sentiment. It wasn't. It was a chaotic, angry, divided mess. There were plots to break the Northwest (states like Ohio and Indiana) away into a separate "Northwest Confederacy." There were secret societies like the Knights of the Golden Circle working to undermine the war effort.

Lincoln also took some heat for civil liberties. He suspended habeas corpus. He shut down some newspapers. Critics called him a "dictator" and "the Great Usurper." The nuance here is that Lincoln was trying to maintain a democracy while using emergency powers to prevent that democracy from being destroyed. It’s a tension we still deal with today.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Citizens

To really understand the election of 1864, you shouldn't just read a textbook. You have to look at the primary sources. Here is how you can actually engage with this history today:

- Read the 1864 Democratic Platform: It’s short. Contrast it with McClellan’s letter of acceptance. You’ll see the exact moment a political party tried to walk a tightrope and fell off.

- Study the "Soldier Letters": Libraries like the Library of Congress have digitized thousands of letters from soldiers home to their families during the election. They describe the visceral hatred for the "Copperheads" back home.

- Visit a "Swing State" of the 1860s: If you’re in the Midwest, look for local historical markers about the Copperhead movement. Places like Indianapolis were hotbeds of anti-war sentiment that nearly boiled over into a second front of the war.

- Analyze the Electoral Map: Look at how the "Border States" like Maryland and Missouri voted. They stayed with Lincoln, which was a huge blow to the Confederacy’s hopes for legitimacy.

The election of 1864 proved that a republic could survive a "ballot box" moment even when the "cartridge box" was still in use. It remains the most important election in American history because it was the one time the country had to choose between a hard peace and an easy surrender, and it chose the hard path.

To dive deeper into this specific era, research the "National Union Party" and how the name change from "Republican" helped Lincoln capture the votes of people who hated his party but loved the country. Understanding that rebranding is key to understanding how he built a winning coalition in a divided North.