Politics today feels like a fever dream, but honestly, it’s got nothing on the absolute chaos of the mid-19th century. If you’ve ever wondered what is the election of 1860, you basically have to imagine a country deciding to pull its own emergency brake at 80 miles per hour. It wasn't just a vote. It was the moment the United States realized it couldn't exist as "half slave and half free" anymore, as Abraham Lincoln famously put it.

The stakes were terrifying.

By the time the 1860 campaign kicked off, the national "vibe" was somewhere between anxious and apocalyptic. You had four major candidates, a political party literally splitting in half during their own convention, and Southerners openly promising to quit the Union if the "Black Republican" won. It's the ultimate example of what happens when a democracy loses the ability to compromise.

The Four-Way Pileup: Who Was Actually Running?

Most people think it was just Lincoln versus everyone else, but it was way messier than that. The Democratic Party, which had been the dominant force for years, basically imploded. They tried to meet in Charleston, South Carolina, but the Northern and Southern wings couldn't agree on a platform regarding slavery in the territories.

The Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas. He was the "popular sovereignty" guy—the idea that people in new states should just vote on whether they wanted slavery or not. Southerners hated this. They felt it didn't go far enough to protect their "property." So, the Southern Democrats broke off and nominated John C. Breckinridge, the sitting Vice President.

Then you had the Constitutional Union Party. These guys were basically the "can't we all just get along?" crowd. They nominated John Bell and had a platform that essentially said, "The Constitution is great, and let's just not talk about the elephant in the room."

📖 Related: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

And then there was Abraham Lincoln.

He wasn't even the favorite for the Republican nomination. Most people expected William H. Seward to take it, but Seward had too much "baggage." Lincoln was seen as a moderate—someone who wouldn't try to abolish slavery where it already existed, but who was rock-solid on stopping it from spreading. To the South, that distinction didn't matter. They saw him as a radical revolutionary.

Why This Vote Was Different

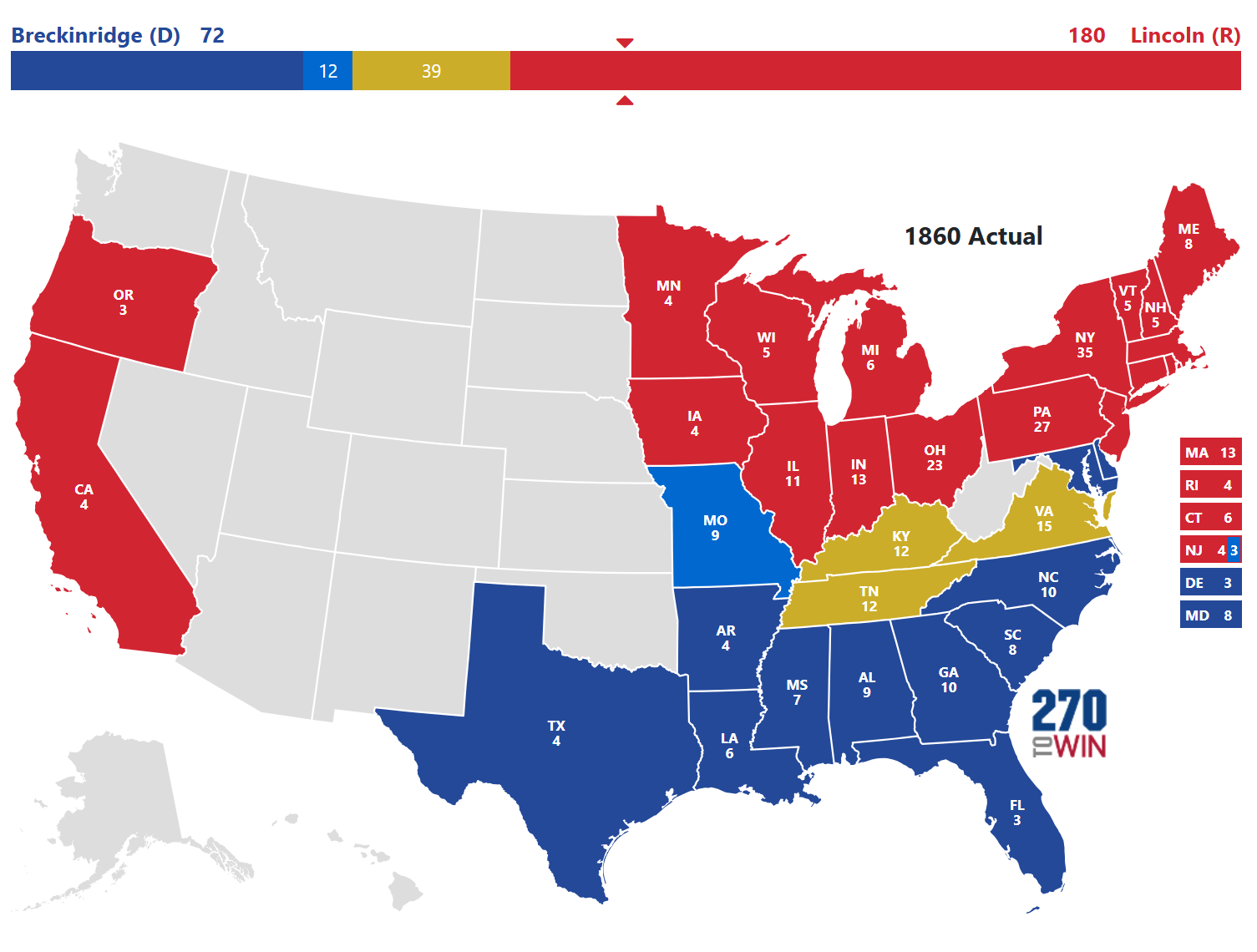

What makes the election of 1860 so unique is how regionalized it was. It was almost like two separate elections happening at the same time. In the North, it was a battle between Lincoln and Douglas. In the South, it was Breckinridge versus Bell.

Lincoln wasn't even on the ballot in ten Southern states. Think about that for a second. A man won the presidency without receiving a single vote in a massive chunk of the country.

The Republican strategy was simple: win the North and the West. They didn't need the South. By focusing on "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men," they tapped into the growing industrial power of the North. They promised higher tariffs to protect factories and a transcontinental railroad. They were building a future that didn't include the plantation system, and the South knew it.

👉 See also: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

The Numbers That Broke the Union

When the dust settled, the results were a mathematical nightmare for unity.

Lincoln pulled about 40% of the popular vote. In a normal year, that's a weak mandate. But because the opposition was so fragmented, he cleaned up in the Electoral College. He won 180 electoral votes. Breckinridge took 72, Bell took 39, and poor Stephen Douglas—who actually had the second-highest popular vote count—only managed to win 12 electoral votes.

It was a total shutout. The South realized they no longer had a "veto" over the national government. The North had the population, the electoral power, and now, the White House.

The Immediate Fallout: Secession and War

People didn't wait around to see what Lincoln would do. He was elected in November; South Carolina left the Union in December. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1861, seven states had already formed the Confederate States of America.

Historians like James McPherson and Eric Foner have pointed out that 1860 was the first time a party explicitly committed to stopping the expansion of slavery actually took power. It was a "regime change" in the truest sense. For the Southern elite, this wasn't just a political loss; it was the end of their entire social and economic world.

✨ Don't miss: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

There's this misconception that Lincoln entered office ready to free the slaves immediately. He didn't. He spent most of his inaugural address trying to tell the South he wouldn't mess with their slaves. But the trust was gone. The election of 1860 had acted as a catalyst, turning decades of tension into an active conflict. Within months, shells were falling on Fort Sumter.

Why We Still Study 1860 Today

It’s the ultimate cautionary tale. It shows what happens when political parties stop being "big tents" and start being "ideological bunkers." When one side of a country feels like it has no path to victory within the existing system, the system breaks.

We see echoes of this whenever people talk about "coastal elites" versus "the heartland." The 1860 map looks hauntingly familiar if you swap the colors and the specific issues. It reminds us that democracy is actually pretty fragile and relies on the losing side believing that they can win the next time. In 1860, the South decided there wasn't going to be a next time they could win.

Actionable Insights: How to Engage with This History

If you want to really get your head around this period, don't just read a textbook. You need to look at the primary sources to see how raw the emotions were.

- Read the 1860 Platforms: Look at the Republican platform versus the Southern Democratic platform. You’ll see two completely different visions for what "America" even meant.

- Check out the "Wide Awakes": Look up this group. They were a paramilitary-style marching organization for the Republican party. It shows how "militarized" even the campaign felt before the war started.

- Visit the Lincoln Home National Historic Site: If you’re ever in Springfield, Illinois, you can see where Lincoln received the news of his victory. It puts the human scale back into a story that feels like it’s only about "Great Men" and "Big Battles."

- Analyze Local Newspapers from 1860: Use digital archives like Chronicling America. Seeing the "fake news" and vitriol of 1860 puts our modern internet arguments into a much-needed perspective. It’s comforting, in a weird way, to know we’ve been this mad at each other before—and we managed to (eventually) put things back together.

The election of 1860 wasn't just a win for the Republican party. It was the moment the United States decided what kind of nation it was actually going to be, even if it had to bleed to get there.