You’ve probably heard people say that modern politics is "polarized." It’s a favorite word for pundits. But if you want to see what actual, bone-deep national fracture looks like, you have to look back at the election of 1860 definition and how it basically functioned as the final snap of a country held together by Scotch tape and prayers.

It wasn't just a vote. It was a divorce filing.

Basically, the election of 1860 was the 19th quadrennial presidential election where Abraham Lincoln, a Republican who wasn't even on the ballot in ten Southern states, won the White House. This wasn't just a "win" in the traditional sense; it was a catalyst. Within months of the results, seven states left the Union. The definition of this election is rooted in the total collapse of the "Big Tent" party system and the rise of sectionalism—where where you lived mattered more than what you believed.

What was the Election of 1860, really?

At its core, the election of 1860 definition refers to the moment the United States stopped talking and started fighting. Before 1860, political parties like the Whigs and the Democrats tried to have a national presence. They wanted voters in both Maine and Mississippi. By 1860, that was dead.

The Democrats, who had been the dominant force, literally split in half during their convention in Charleston. They couldn't agree on a platform regarding slavery in the territories. Northern Democrats wanted "popular sovereignty" (letting locals decide), while Southern Democrats wanted a federal slave code to protect their "property" everywhere. They walked out. They held separate conventions. It was a mess.

While the Democrats were imploding, a relatively new party called the Republicans was gaining steam. They weren't abolitionists in the way we think of them today—most weren't looking to end slavery where it already existed—but they were adamant about "Free Soil." They didn't want slavery moving west. They nominated Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer from Illinois with a knack for storytelling and a reputation for being moderate enough to win the North.

The Four-Way Train Wreck

We usually think of elections as a two-man race. Not this time. 1860 was a four-way chaotic scramble.

- Abraham Lincoln (Republican): Stood for high tariffs, a transcontinental railroad, and no expansion of slavery.

- Stephen A. Douglas (Northern Democrat): The "Little Giant." He argued for popular sovereignty. He was the only candidate who really campaigned nationwide, but he ended up with very few electoral votes.

- John C. Breckinridge (Southern Democrat): The sitting Vice President. He was the choice of the hardline South. He wanted the Supreme Court and the federal government to protect slavery at all costs.

- John Bell (Constitutional Union): Basically the "Can’t We All Just Get Along?" candidate. His party had one platform: "The Constitution of the Country, the Union of the States, and the Enforcement of the Laws." He won three border states.

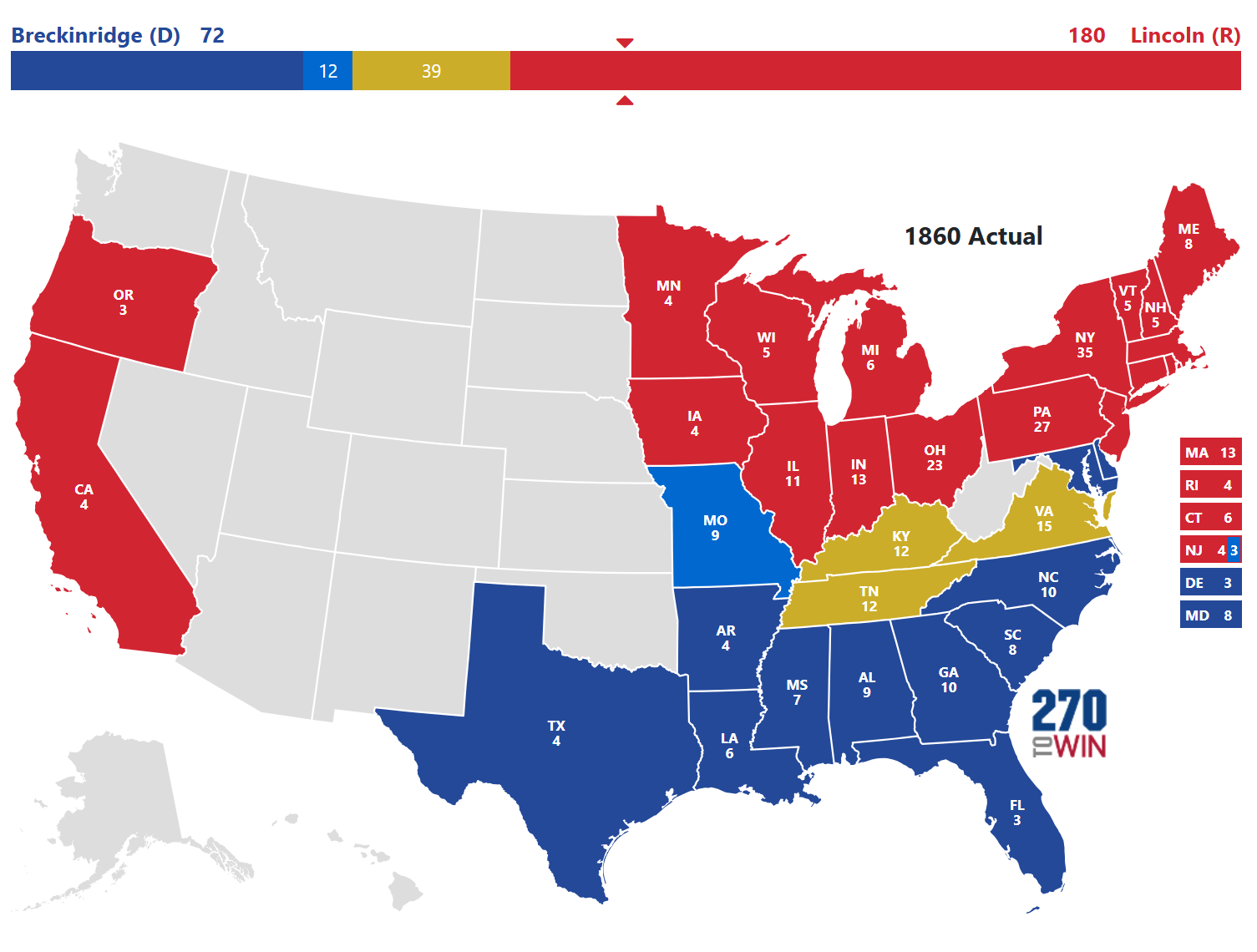

The math was brutal. Lincoln won 40% of the popular vote but 180 electoral votes. He swept the North and the West. He didn't need a single vote from the South to win the Presidency.

That was the "Aha!" moment for Southern leaders. They realized they no longer had a say in the national government. The demographic shift toward the industrial North meant the South was now a permanent minority. Honestly, that realization is what triggered the secession winter of 1860-1861.

Why the "Definition" is Often Misunderstood

A lot of people think the election was a referendum on "Ending Slavery Now." It wasn't.

👉 See also: What Democrats Voted for the Bill: Tracking the Power Players and the Holdouts

If you look at the Republican platform of 1860, it was actually quite conservative regarding existing state laws. They explicitly stated they wouldn't interfere with slavery where it already existed. They just wanted to stop it from spreading. But the South didn't believe them. To the planter class, any restriction on the expansion of slavery was a death sentence for the institution. They saw Lincoln as a "Black Republican" radical.

The Myth of the Unanimous North

Don't think the North was a monolith. New York City, for example, was terrified of a Lincoln win. The city’s economy was tied to Southern cotton. There was even talk of NYC seceding to become a "free city" so they could keep trading with the South. Lincoln won the state, but the internal tension was thick enough to cut with a knife.

The election also featured some of the nastiest rhetoric in American history. People weren't just disagreeing; they were calling each other traitors and tyrants. Southern newspapers warned that a Lincoln victory would lead to "hundreds of thousands of our slaves... emancipated and turned loose among us." Fear-mongering was the primary campaign tool.

The Fallout: From Ballots to Bullets

When the news of Lincoln’s victory hit the wires via the telegraph, South Carolina didn't wait. They called a convention and left the Union in December.

💡 You might also like: Nancy Parker Facebook Post: The Tragic Truth and Why New Orleans Never Forgot

This is the most critical part of the election of 1860 definition: it proved that the democratic process only works when both sides agree to lose. In 1860, the South refused to accept the outcome. They viewed the election of a sectional candidate as an act of war.

It’s kind of wild to think about. Lincoln wasn't even inaugurated until March 1861. By the time he took the oath of office, the Confederate States of America had already formed their own government and seized federal property. He inherited a house that was already on fire.

Nuance Matters: The Role of the Constitutional Union Party

We often ignore John Bell, but his role was fascinating. He represented the "Old Gentlemen's Party." These were people who were terrified of the Republicans but also disgusted by the radical "Fire-Eaters" of the South. They wanted to pretend the issue of slavery could just be ignored. Their presence in the race actually helped Lincoln by splitting the opposition in key states.

If the Democrats hadn't split, could they have beaten Lincoln? Probably not. The math suggests that even if you combined all of Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell’s votes in the North, Lincoln still would have won the majority of the electoral college. The North had the population. The South had the anxiety.

Actionable Insights: How to Study 1860

To truly understand this pivotal year, you need to go beyond the textbooks.

💡 You might also like: IRS Automatic Payments Stimulus Checks: Why You Might Still Be Waiting

- Read the Party Platforms: Don't take a historian's word for it. Look up the 1860 Republican Platform and the two different Democratic platforms. You’ll see exactly where the lines were drawn.

- Analyze the County Maps: Look at the voting results by county, not just by state. You’ll see "pockets of Unionism" in the South (like in East Tennessee or Western Virginia) where people actually voted against the secessionist candidates.

- Trace the Logistics: Look at how the telegraph and the railroad changed this election. This was the first "modern" election where information moved faster than a horse, which accelerated the panic after Lincoln’s win.

- Examine the Primary Sources: Check out the Richmond Enquirer or the Chicago Tribune from November 1860. The tone is jarringly modern in its hostility.

The election of 1860 serves as a stark reminder that when political parties stop being national and start being regional, the center rarely holds. It wasn't just about Lincoln; it was about a system that had run out of compromises.

To dig deeper into the actual documents of the era, the Library of Congress digital archives host the "Abraham Lincoln Papers," which include letters from terrified citizens and angry politicians during the months between his election and his inauguration. Seeing the handwriting of the people who lived through it makes the "definition" feel a lot more real than a paragraph in a textbook.