Andrew Jackson won. If you just wanted the name, there it is. But honestly, saying Andrew Jackson won the election of 1828 is like saying the Titanic had a minor plumbing issue. It misses the absolute chaos of what actually happened.

This wasn't just a vote. It was a cultural earthquake that shattered the "Era of Good Feelings" into a million jagged pieces. You had John Quincy Adams—the incumbent, a brilliant but stiff intellectual—facing off against Jackson, a man who had literally killed people in duels and survived with bullets still lodged in his chest.

It was messy.

The Rematch Nobody Wanted (But Everyone Watched)

To understand why the election of 1828 turned into a mud-slinging festival, you have to look back at 1824. Jackson had won the popular vote back then, too. But because nobody got an electoral majority, the House of Representatives handed the presidency to Adams. Jackson called it a "Corrupt Bargain." He spent four years stewing. He was angry. His supporters were angrier.

By 1828, the gloves weren't just off; they were burned.

This was the first time we saw "mudslinging" as a primary campaign strategy. The Adams camp went after Jackson’s wife, Rachel, calling her an adulteress because her divorce from her first husband hadn't been finalized when she married Jackson. It was brutal. Jackson, in turn, accused Adams of being a pimp who procured American girls for the Russian Czar while serving as a diplomat.

✨ Don't miss: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

Is any of that true? The Rachel stuff was a legal technicality. The pimp stuff? Totally baseless. But in 1828, the truth was secondary to the vibe.

Why the Map Turned Blue (and Yellow)

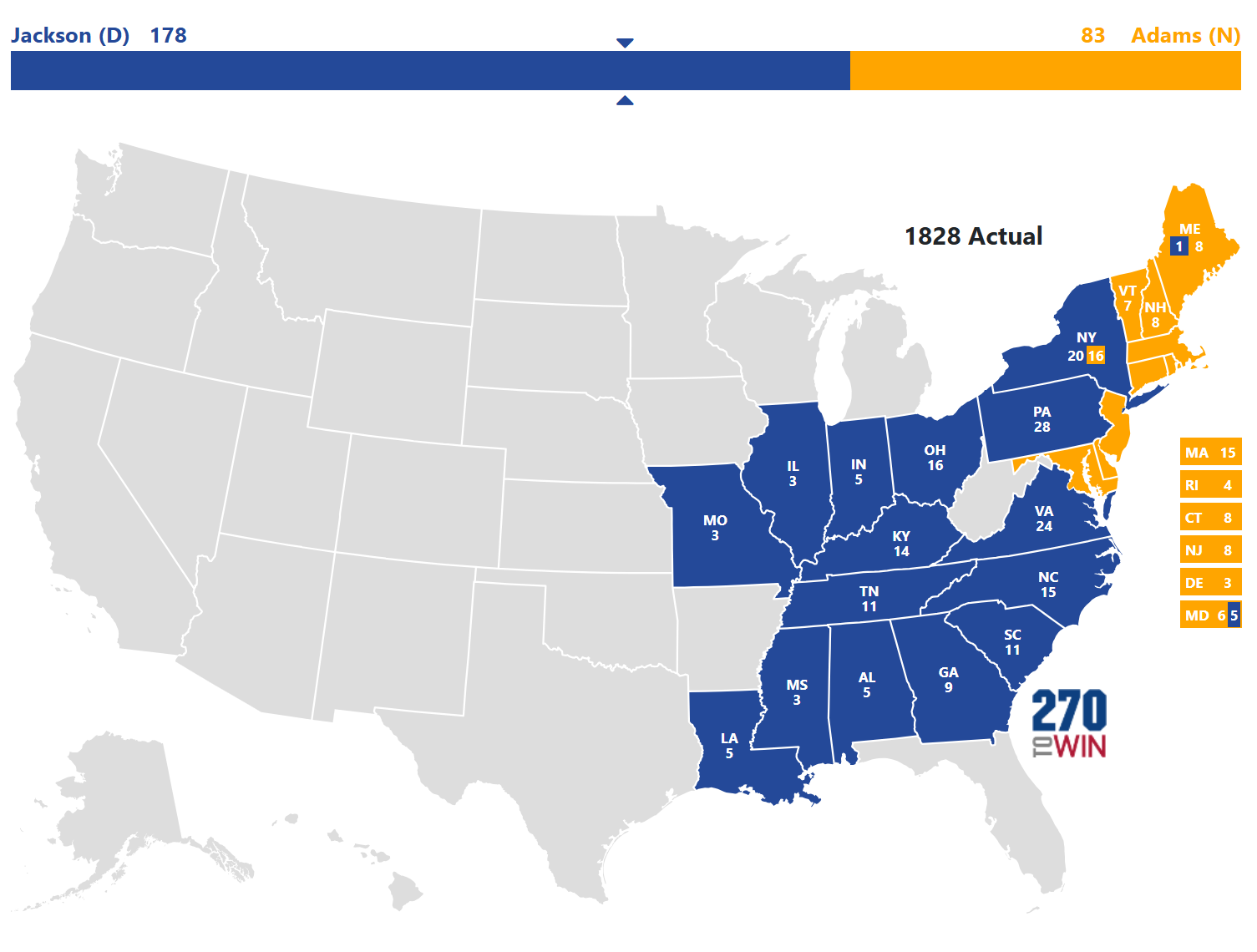

The electoral map tells the real story of who won the election of 1828. Jackson swept the South and the West. Adams held onto New England. It was a total geographic split.

Jackson tapped into a new kind of voter: the "common man." Before this era, in many states, you had to own property to vote. By 1828, those rules were vanishing. This was the dawn of "Jacksonian Democracy." Thousands of farmers, frontiersmen, and city laborers who felt ignored by the "Virginia Dynasty" and the Boston elites suddenly had a voice.

They used it.

Jackson secured 178 electoral votes to Adams' 83. It wasn't even close in the end. He won the popular vote by about 140,000 votes, which, for a country that only saw about 1.1 million people go to the polls, was a massive mandate.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

The Secret Weapon: Martin Van Buren

If Jackson was the face of the movement, Martin Van Buren was the brain. Van Buren—often called the "Little Magician"—basically invented the modern political party during this cycle. He realized that to win, you couldn't just have a candidate; you needed a machine.

He organized local committees. He staged parades. He printed "Hickory" newspapers. He turned Jackson into a brand. "Old Hickory" wasn't just a nickname; it was a symbol of toughness that people could buy into.

The Tragedy Behind the Triumph

There's a dark note to this victory that historians often gloss over. Jackson won, but he lost his heart. His wife, Rachel, died of a heart attack just weeks after the election but before the inauguration. Jackson blamed the Adams campaign’s personal attacks for her death.

"I can and do forgive my enemies," he reportedly said. "But those vile wretches who have slandered her must look to God for mercy."

He arrived in Washington D.C. a widower, draped in black, harboring a grudge that would define his entire presidency. When he was inaugurated, the crowd was so wild they literally tore the White House apart. People were climbing through windows and breaking china just to get a glimpse of their hero. The "common man" had arrived, and the elites were terrified.

💡 You might also like: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Why 1828 Changed Everything Forever

We still live in the world created by the election of 1828. This was the birth of the Democratic Party. It was the moment politics stopped being a gentleman's debate and started being a blood sport.

Jackson’s win signaled a shift in power from the Atlantic coast to the interior of the country. It also cemented the "Spoils System"—the idea that if you win the election, you fire everyone in the government and hire your friends. It was messy, it was loud, and it was undeniably American.

Historians like Jon Meacham and H.W. Brands have noted that Jackson’s presidency was a turning point for executive power. He used the veto more than all previous presidents combined. He ignored the Supreme Court. He was, in many ways, the first "imperial" president, all because of the momentum he built during that 1828 campaign.

Key Takeaways and What to Do Next

If you’re a student of history or just someone trying to understand why American politics is so polarized today, the 1828 cycle is your ground zero. It teaches us that personality often trumps policy and that a well-organized grassroots movement can topple any establishment.

Actionable Steps for the History Buff:

- Read the primary sources: Look up the "Coffin Handbills" used against Jackson. They are a masterclass in early negative campaigning.

- Visit the Hermitage: If you’re ever in Nashville, Jackson’s home provides a visceral look at the man who won—and what he lost—in 1828.

- Analyze the 1824 vs. 1828 maps: Comparing these two elections shows exactly how the "Corrupt Bargain" narrative shifted the American electorate.

- Look for modern parallels: Notice how "populism" today mirrors the rhetoric used by Jackson’s supporters to describe the "corrupt" elites in Washington.

The 1828 election wasn't just a win for a man; it was the birth of a brand-new political reality. Understanding it is the only way to truly understand the modern United States.