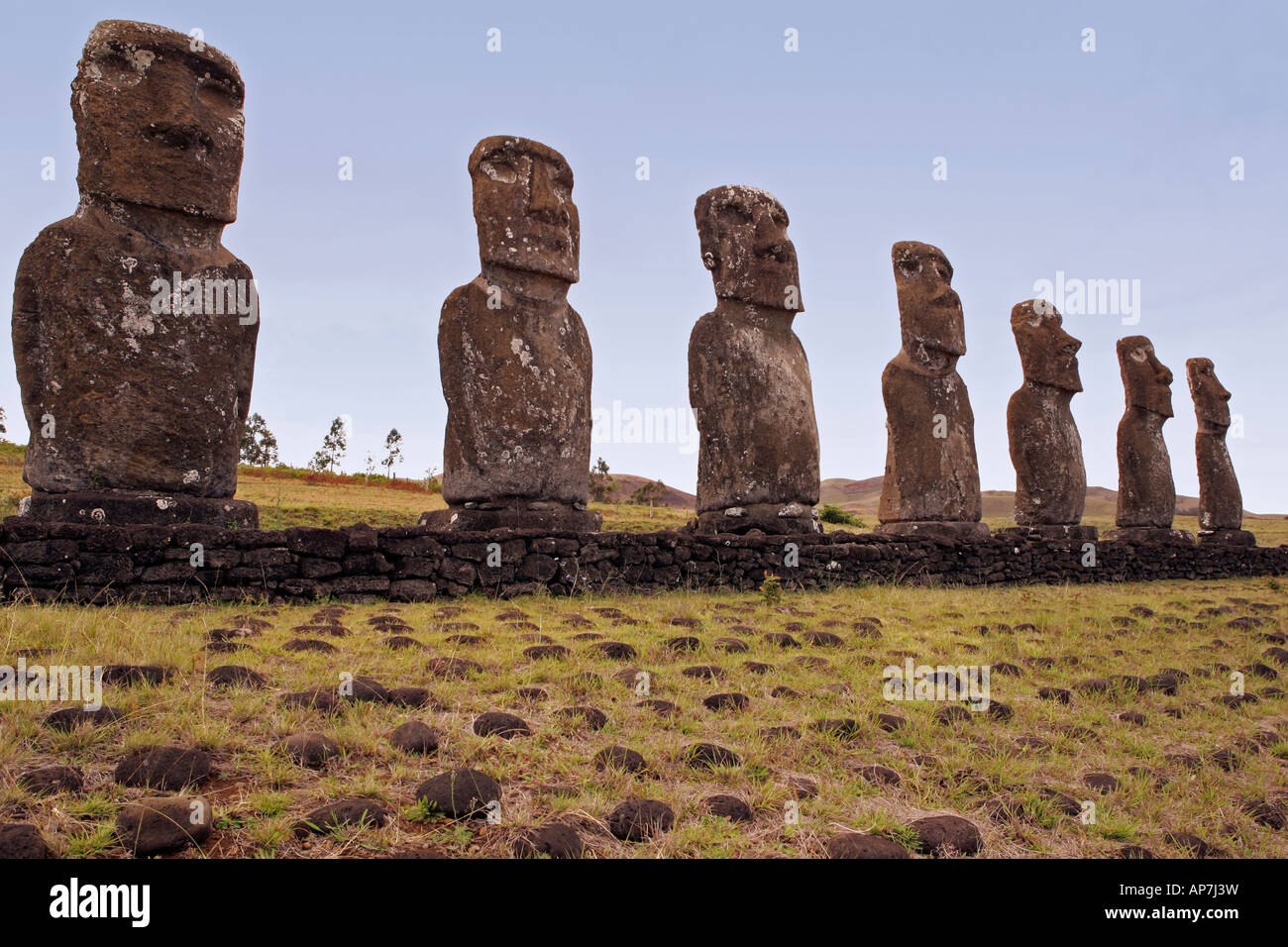

When you picture Rapa Nui, better known as Easter Island, you probably see those giant, brooding stone faces staring blankly across the grassy hills. They're iconic. But look closer at the ones standing on the ceremonial platforms, or ahu. Some of them are wearing massive, reddish-brown cylinders on their heads. People call them easter island statues hats, but that’s not really what they are.

They’re called pukao.

And honestly? They are a feat of engineering that makes the statues themselves look like a warm-up act. Imagine carving a 12-ton block of volcanic rock, hauling it across miles of rugged terrain without wheels, and then somehow—against all laws of common sense—hoisting it ten feet into the air to balance it on top of a narrow stone head. It sounds impossible. Yet, there they are.

What Are the Easter Island Statues Hats, Really?

If you ask a local or a seasoned archaeologist like Jo Anne Van Tilburg, who has spent decades studying these monoliths, they’ll tell you "hat" is a bit of a misnomer. These things represent hair. Specifically, they represent a topknot or a bun, which was a sign of status and mana (spiritual power) among the Rapa Nui people.

The rock isn't the same stuff as the statues. While the moai (the statues) were carved from a yellowish-gray tuff at the Rano Raraku quarry, the pukao came from a completely different spot called Puna Pau. It’s a small scoria cone where the rock is a deep, oxidized red. This color was sacred. It’s the color of blood, the color of the earth, and the color of high-ranking royalty.

The Puna Pau Connection

Puna Pau is a weird place. It’s a crater filled with soft, red volcanic stone that’s actually quite easy to carve compared to the harder basalt found elsewhere on the island. When you visit today, you can still see unfinished pukao lying in the grass. Some are huge. We’re talking nearly 8 feet in diameter.

Why go through the trouble? Why not just carve the hat as part of the head?

Basically, it's about prestige. By using two different types of stone from two different quarries, the Rapa Nui were showing off. It was a massive flex of communal labor and resources. You weren't just building a monument; you were coordinating a multi-village logistics operation that required hundreds of people to be fed and managed for months at a time.

👉 See also: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

How the Heck Did They Get Up There?

This is the part that keeps researchers up at night. For a long time, the leading theory was that the Rapa Nui built giant dirt ramps. They’d drag the pukao up the ramp, slide it onto the head, and then dig the dirt away. It's a solid theory. It works. But it also requires an insane amount of extra work.

A few years ago, researchers from Penn State and the University of Oregon, including Sean Hixon and Carl Lipo, came up with a much more elegant solution: parbuckling.

If you’ve ever rolled a heavy barrel up a ramp using a rope looped around it, you’ve parbuckled. By using a long ramp made of wood and a clever rope system, a relatively small group of people—maybe 15 or 20—could roll a multi-ton pukao up to the top of a moai. This theory explains why many pukao have flat edges or indentations that would help them stay centered as they rolled. It’s physics, not magic.

Why the Pukao Matter More Than You Think

It’s easy to get distracted by the "how" and forget the "why." These easter island statues hats weren't just decorative. They marked a specific era in the island's history.

Most of the hats were added later in the statue-building period, roughly between 1200 and 1600 AD. This was a time when the island’s society was becoming more complex and, eventually, more strained. The statues started getting bigger. The hats started getting bigger. It was an arms race of stone.

- Mana: The topknot was believed to be where a person's power resided.

- Lineage: Each moai represented a specific ancestor. The pukao gave that ancestor back their dignity and status.

- Stability: Interestingly, the weight of the pukao actually helped stabilize the statues against the island's fierce winds, acting like a giant paperweight.

The Great Toppling

If you go to Rapa Nui today, you’ll notice something sad. Most of the statues with hats are actually lying face down in the dirt, their "hats" scattered nearby like dropped marbles.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, internal warfare and societal shifts led the Rapa Nui to stop building statues and start knocking them down. Pulling down an enemy's moai and knocking off its pukao was the ultimate insult. It was a way of "blinding" the ancestor and stripping the village of its spiritual protection. It’s why so many of the hats you see in photos are chipped or broken—they didn't just fall; they were pushed.

✨ Don't miss: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

You've probably heard the story that the islanders cut down every single tree to move these statues and hats, leading to a "suicidal" ecological collapse.

Actually, that's mostly a myth popularized by Jared Diamond’s book Collapse. Modern archaeological evidence, including work by Terry Hunt, suggests the story is way more nuanced. While deforestation did happen, it was partly caused by Polynesian rats eating palm seeds, and the society didn't just "disappear." They adapted. They moved to rock mulch farming. They survived long after the last statue was carved. The easter island statues hats weren't the cause of their downfall; they were a testament to their resilience and ingenuity.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Shapes

If you look closely at a pukao, it isn't a perfect cylinder. It has a small depression on the bottom to fit onto the head, and often a smaller knob or "topknot" on top of the main cylinder.

Some people think these were crowns. Others think they were helmets. But when you look at traditional Rapa Nui hairstyles recorded by early European explorers, the resemblance to a tied-up bundle of hair is unmistakable. The red scoria even mimics the reddish tint some islanders gave their hair using pigments.

The Logistics of the Red Stone

Transporting a pukao from Puna Pau to the coast wasn't just about strength. It was about geography. The island is small, but the terrain is treacherous.

The Rapa Nui didn't use wheels. They used "moai roads"—carefully cleared paths that avoided steep grades. They likely moved the hats by rolling them, which is why the pukao are round. It’s a classic example of form following function. You carve the stone into a shape that is easy to move, and then you do the final detailing once it reaches its destination.

Why Red?

Why go to Puna Pau at all? There are other red rocks on the island.

🔗 Read more: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

The scoria at Puna Pau is unique because it’s full of air pockets. This makes it significantly lighter than the basalt or tuff used for the statues. If they had tried to make hats out of the same heavy stone as the bodies, they probably never would have gotten them onto the heads. The Rapa Nui were master geologists; they knew exactly which stone offered the best strength-to-weight ratio.

How to See Them Today

If you’re planning a trip to Rapa Nui, you can't just walk up and touch them. The island is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a protected national park (Parque Nacional Rapa Nui).

- Ahu Tongariki: This is the big one. Fifteen statues in a row, many of them wearing their pukao. It’s the best place to see the scale of the hats against the Pacific Ocean.

- Anakena Beach: The moai here are some of the best-preserved on the island because they were buried in sand for centuries. Their hats are still incredibly detailed.

- Puna Pau: Don't skip the quarry. Seeing the "hat factory" gives you a sense of the sheer volume of production that was happening.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Traveler or History Buff

If you’re fascinated by the engineering of the easter island statues hats, there are a few things you should do to deepen your understanding beyond a Google search.

First, look into the work of the Easter Island Statue Project (EISP). They have the most extensive database of statue measurements and photos in existence. It’s where the real science happens.

Second, if you visit, hire a local Rapa Nui guide. There is a massive difference between "textbook" history and the oral traditions passed down by the descendants of the people who actually moved these stones. They can point out the subtle "cupules" (small carved pits) on the hats that tourists usually miss.

Third, pay attention to the erosion. The red scoria is much softer than the statue stone. It’s weathering away faster. In fifty years, the fine details on many of these "hats" might be gone forever. Seeing them now is a privilege.

The pukao are a reminder that human beings have always been willing to do "unnecessary" work for the sake of art, religion, and ego. We don't just build things that work; we build things that mean something. Whether it’s a skyscraper in Dubai or a red stone topknot on a remote Pacific island, the impulse is the same. We want to be seen. We want to be remembered. And we want to show that we can move mountains—or at least, very large pieces of them.

Next Steps for Your Research

To get the full picture of Rapa Nui's history, start by looking at the climate records of the Pacific from 1200-1600 AD. This explains why the statue-building culture eventually shifted. Also, check out the recent DNA studies that have debunked the idea of a pre-European "collapse" by showing the population remained stable and diverse. Understanding the hats requires understanding the people, and the people of Rapa Nui were far more successful and clever than the old "mystery" documentaries ever let on.