Paul Schrader is a legend. You know him as the guy who wrote Taxi Driver and directed First Reformed. He’s not exactly known for playing nice with studios. So, when the Dying of the Light movie hit theaters back in 2014, something felt... off. It wasn’t just a bad movie; it felt like a ghost of a movie. It felt like someone had taken a sharp, jagged piece of art and sanded it down until it was a smooth, boring pebble.

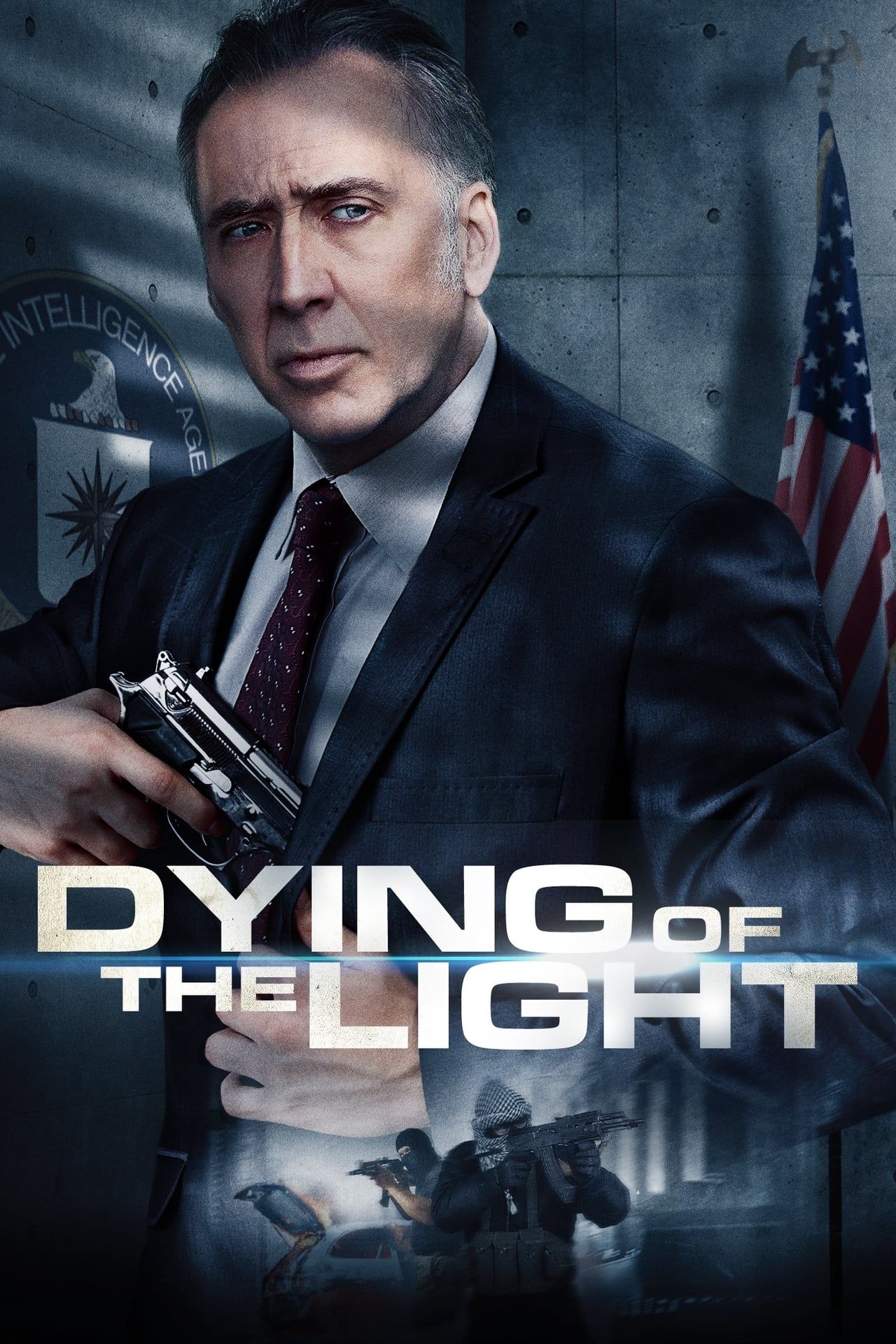

Nicholas Cage stars as Evan Lake. He’s a veteran CIA agent battling early-onset dementia while hunting down a terrorist who tortured him years ago. On paper, it’s a brilliant, tragic setup. In reality? The version that was released to the public was a mess of generic editing and flat pacing.

The story behind the camera is actually way more interesting than the thriller we saw on screen. It’s a cautionary tale about creative control, the "final cut" privilege, and what happens when a studio gets cold feet. Basically, Lionsgate and Grindstone took the footage away from Schrader and re-edited it without his input. They locked him out of the room. He wasn't even allowed to finish the color grading or the sound mix.

What went wrong with the Dying of the Light movie?

Movies get taken away from directors all the time. It’s the ugly side of Hollywood. But this was different because Schrader didn't just walk away quietly. He, along with Cage and co-stars Anton Yelchin and Irene Jacob, staged a "silent" protest. They wore T-shirts that quoted the "non-disparagement" clauses in their contracts. It was a brilliant, passive-aggressive move.

The producers, including Todd Williams and those at Grindstone Entertainment, claimed they stepped in to make the film "commercially viable." They thought Schrader’s version was too slow. Too experimental. Maybe too depressing. By trying to make it a standard Nicolas Cage action flick, they killed the soul of the project.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Cage's performance is actually quite good if you look past the choppy editing. He plays the cognitive decline with a desperate, shaky energy that feels very real. It's a shame. You can see glimpses of a much better film buried under the generic "straight-to-video" aesthetic that the studio forced upon it.

The leaked "Dark" version

Schrader eventually did something radical. He couldn't legally release his cut of the Dying of the Light movie, so he essentially made a "remix." He took the footage he had access to, which was low-quality, and re-edited it himself. He called it Dark.

He didn't sell it. He just put it out there. He even donated the files to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin so film students could see what he intended. Dark is a different beast entirely. It’s more abrasive. It’s weirder. It actually leans into the disorientation of the main character’s dementia. If you've only seen the theatrical version, you haven't really seen the movie Schrader wanted to make.

Why the movie's failure still matters for cinema history

This isn't just about one bad movie. It’s about the death of the mid-budget auteur film. In the 70s, Schrader would have been given a long leash. In 2014, he was treated like a hired hand. The Dying of the Light movie represents a specific moment in the industry where studios became terrified of anything that didn't fit a specific algorithm.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

- The theatrical cut sits at a dismal 11% on Rotten Tomatoes.

- Critics like Ben Kenigsberg noted that the film felt "gutted."

- The cinematography by Gabriel Beristain was supposedly altered significantly in post-production.

Honestly, it’s a tragedy. Anton Yelchin, who played the young protégé, gave a subtle, grounded performance that was largely wasted in the final edit. It was one of his final roles before his passing, which adds another layer of sadness to the whole ordeal.

Schrader once said that the studio "vandalized" his work. That's a strong word, but when you compare the theatrical release to his Dark cut, it's hard to disagree. The studio version tries to be a revenge thriller. Schrader’s version is a meditation on mortality and the loss of self.

How to actually watch the "Real" version

You won't find the director's cut on Netflix or Max. It’s not on Amazon Prime. Because of the legal battles, the "official" version will always be the one Schrader hates. However, if you are a cinephile, searching for the Dark cut or visiting the Ransom Center archives is the only way to get the full picture.

The differences aren't just subtle tweaks. We're talking about different scenes, different music, and a completely different ending. The theatrical ending feels like a standard shootout. The Dark ending feels like a fever dream.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Actionable insights for the curious viewer

If you're planning to revisit the Dying of the Light movie, don't go in expecting John Wick. Go in with the knowledge that you are watching a compromised vision.

First, watch the theatrical version just to see the "baseline." It’s available on most VOD platforms for a few bucks. Pay attention to the cuts—they're often jarring and don't match the emotional beats of the actors.

Second, seek out the interviews Paul Schrader gave around 2014 and 2015. He’s incredibly blunt about the process. Reading his Facebook posts from that era is like taking a masterclass in how the studio system can break a director's spirit.

Lastly, compare this to Schrader’s later success with First Reformed and The Card Counter. Those films were made with more creative freedom, and the difference in quality is staggering. It proves that the problem with Dying of the Light wasn't the script or the acting—it was the interference.

To truly understand the film, you have to look at it as a crime scene. The evidence of a great movie is all over the place, but the body has been moved. Study the lighting in the torture flashbacks. Look at how Cage uses his eyes to convey confusion. There is a masterpiece in there somewhere, even if the version on your TV screen is just a shadow of it.

The best way to support the legacy of this film is to treat it as a lesson. Support indie distributors like A24 or NEON that allow directors to keep their final cut. The Dying of the Light movie serves as a permanent reminder that in Hollywood, the person with the money often has the power to destroy the art, but they can't quite erase the director's original intent if the director is loud enough about it.