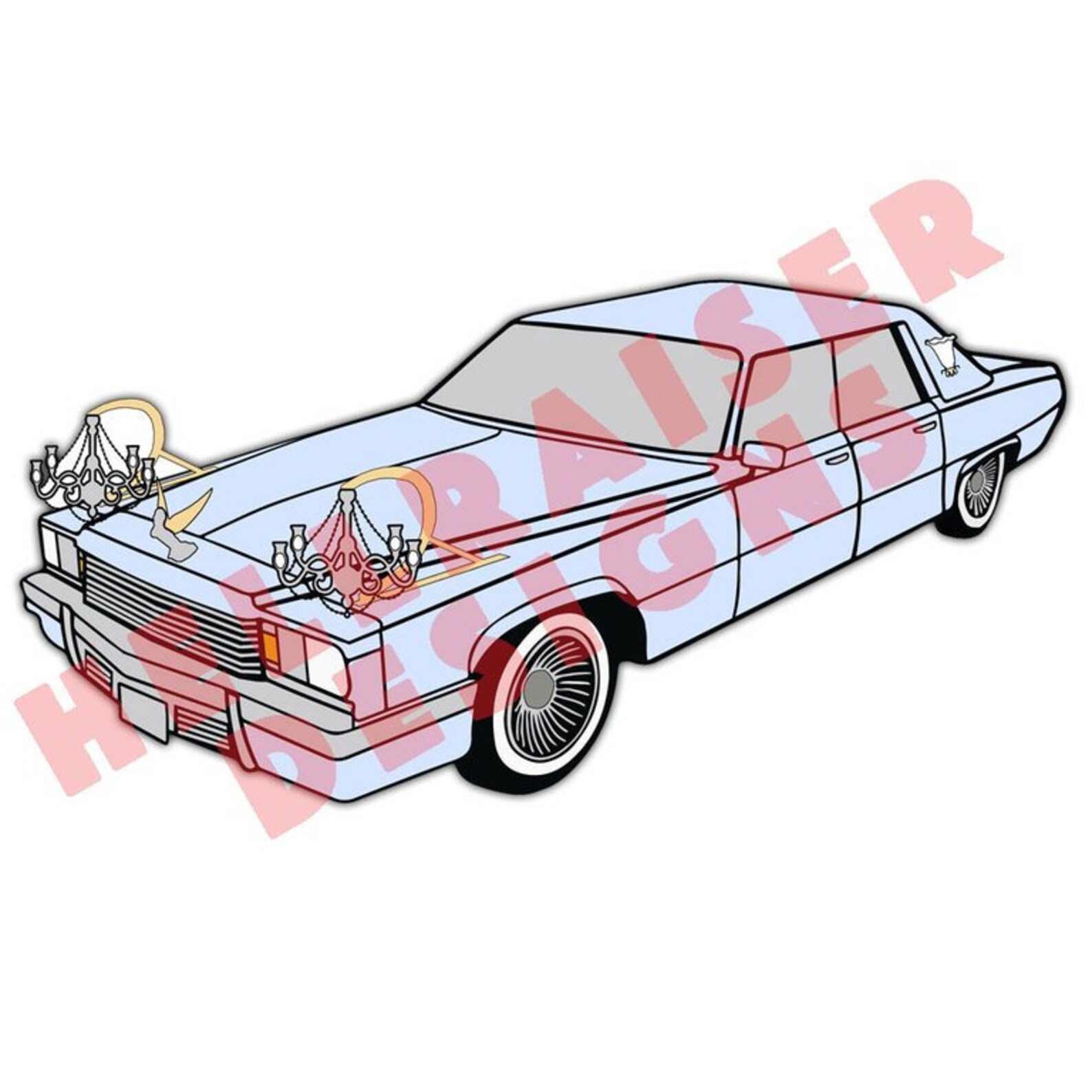

He rolls up in a Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham draped in chandeliers. Literally. It’s the ultimate 1981 vision of a post-apocalyptic warlord, and yet, somehow, it works. When we talk about The Duke Escape from New York fans remember most, we aren’t just talking about a villain; we’re talking about the gravitational pull of Isaac Hayes. John Carpenter’s 1981 masterpiece didn't just give us Snake Plissken. It gave us a vision of Manhattan turned into a maximum-security prison, presided over by a man who didn't need a crown to prove he was royalty.

The Duke is the "A-Number-One" guy.

He’s the boss of the largest gang in the walled-off island of Manhattan. While the United States Police Force (USPF) cowers behind the barricades of the Liberty Island security center, the Duke is the one actually running the show. He holds the President of the United States captive after Air Force One is hijacked and crashed into the urban jungle. This isn't just a kidnapping. It's a political chess move in a world that has completely lost its mind.

Honestly, looking back at the film now in 2026, the world Carpenter built feels strangely prophetic in its cynicism, though thankfully we haven't turned the Bronx into a literal minefield yet.

Making a Legend: Behind the Casting of Isaac Hayes

Casting the Duke was a make-or-break moment for the movie. If the villain felt like a caricature, the whole "New York as a prison" conceit would have collapsed into B-movie camp. Carpenter originally thought about different types of actors, but then he landed on Isaac Hayes. It was a stroke of genius. Hayes brought that deep, resonant baritone and a physical presence that felt immovable. He didn't have to scream to be terrifying. He just had to stand there.

The Duke of New York is a man of few words. He lets his "Duke-mobiles" do the talking. You remember those cars, right? The 1977 Cadillac Fleetwood with the chandeliers mounted on the fenders? It’s arguably one of the most iconic pieces of production design in 80s cinema. It was ridiculous. It was flashy. It was exactly what a man who conquered the ruins of the World Trade Center would drive.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Hayes didn't play him like a crazy person. He played him like a CEO who happened to use a submachine gun. That’s why The Duke Escape from New York remains such a standout character; he is a mirror to the government officials outside the wall. He wants the same thing they do: power and a way out. He’s just more honest about the violence required to get it.

The Power Dynamics of the Island

Manhattan in the film is divided. It’s not just one big happy family of criminals. You have the Crazies who live in the sewers and come out at night to eat people. You have the Skulls. But everyone answers to the Duke.

His headquarters were situated in the remains of the World Trade Center, which, in 1981, represented the pinnacle of American economic might. Placing the Duke there was a deliberate visual metaphor. He had taken the heart of the "old world" and repurposed it for his own brand of feudalism. When Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) enters the city, he isn't just fighting a clock; he's navigating a complex social hierarchy where the Duke sits at the very top.

- The Leverage: The Duke has the President (Donald Pleasence).

- The Demand: Total amnesty for all prisoners on the island and a bridge to the mainland.

- The Muscle: A small army of loyalists and those iconic, candle-lit Cadillacs.

The interaction between the Duke and the President is one of the darkest parts of the film. The Duke doesn't just want the President for a bargaining chip. He wants to humiliate the office. He forces the leader of the free world to use a target for target practice, mocking the very concept of American authority. It’s visceral. It’s mean. It’s perfect for the tone Carpenter was hitting.

Why the Duke Failed (and Why Snake Succeeded)

The Duke’s downfall is a classic case of hubris. He thought he was untouchable because he had the "tape"—the recording about cold fusion that was the key to preventing a global war. He assumed that because he held the most valuable person and the most valuable object in the world, the rules of the game had changed in his favor.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

But Snake Plissken doesn't care about the rules. Snake is a nihilist.

The Duke’s biggest mistake was engaging in the "gladiatorial" combat at his headquarters. He forced Snake to fight Slag in a wrestling ring surrounded by spikes. It was a show of power, but it wasted time. In the world of The Duke Escape from New York, time is the only currency that matters because of those microscopic explosives in Snake’s neck.

The final chase across the 59th Street Bridge—which they actually filmed in St. Louis because New York was too expensive and didn't look "gritty" enough—is where the Duke meets his end. It’s a messy, violent conclusion. He’s blown up by his own minefield, and then the President—the very man he humiliated—is the one who finally pulls the trigger. There’s a poetic irony there. The "A-Number-One" guy gets taken out by the "weak" man he thought he had broken.

The Cultural Impact of the Duke

We don't get modern cinematic warlords without the Duke. Think about the villains in Mad Max: Fury Road or even some of the gang leaders in The Warriors. The Duke set the template for the "sophisticated barbarian." He wasn't just a thug in a leather jacket. He was a man with a vision, a style, and a code—even if that code was "do what I say or die."

Isaac Hayes’ performance also broke barriers. Seeing a Black man as the undisputed king of a dystopian New York, commanding a diverse army of followers, was a powerful image in 1981. He wasn't a sidekick. He wasn't a secondary threat. He was the main event.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Real-World Filming Facts

If you're a trivia nerd, you'll love this: the production actually bought the rights to film in East St. Louis because a massive fire had recently gutted parts of the city, making it look exactly like a war zone. They didn't have to build many sets. They just moved in and started shooting. The "Duke's" car was actually built by a local customizer, and Isaac Hayes reportedly loved the vehicle so much he wanted to keep it. Can you blame him?

Navigating the Legacy

If you’re looking to revisit the film or understand the character’s depth, you have to look past the action beats. The Duke represents the fear of urban decay that gripped America in the late 70s and early 80s. New York was seen as a "lost" city back then, plagued by crime and financial ruin. Carpenter just took that fear to its logical, cinematic extreme.

The Duke is the personification of that "lost" city fighting back. He is the king of the trash heap, and he wears that title with more dignity than the politicians who put him there.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

To truly appreciate the nuances of the character and the film's production, consider these steps:

- Watch the 4K Restoration: The lighting in Escape from New York is notoriously difficult because it was shot mostly at night with low light. The recent 4K scans bring out the detail in the Duke’s costume and those Cadillac chandeliers that you simply couldn't see on VHS or DVD.

- Analyze the Score: Isaac Hayes was a legendary musician, but John Carpenter (and Alan Howarth) did the music for the film. Listen to the "Duke Arrives" theme. It’s a rhythmic, pulsing synth track that perfectly matches the gait of Hayes’ performance.

- Check the Deleted Scenes: There is an original opening to the film involving Snake robbing a bank that was cut. Watching it changes your perspective on why the Duke and Snake are actually two sides of the same coin. They are both outcasts; one just decided to build a kingdom while the other decided to burn everything down.

- Explore the Comic Tie-ins: There are several comic book series (published by Marvel and later BOOM! Studios) that expand on the lore of the Duke’s rise to power. If you want to know how a prisoner became the "A-Number-One" guy, the comics provide a gritty backstory that the movie only hints at.

The Duke isn't just a villain in a cult classic. He’s a reminder of a time when movie characters were defined by their presence and their silhouette. In a world of CGI villains and over-explained backstories, there’s something refreshing about a guy who just shows up in a chandelier-clad Cadillac and demands the world. He was the king of New York, even if the kingdom was a prison.

The best way to honor that performance is to watch the film again and pay attention to Hayes' eyes. He’s not playing a monster. He’s playing a man who won. Until, of course, he met Snake.

To get the most out of your next rewatch, pay close attention to the bridge sequence. Notice how the Duke’s death isn't a heroic sacrifice or a grand monologue—it's sudden, chaotic, and almost accidental. It reinforces the film's central theme: in a world this broken, nobody is special, not even the Duke. This grounded approach to character death is what keeps the film feeling "real" decades later. Keep an eye out for the small details in his final moments; the desperation in his eyes proves that even the King of New York knew when his reign was over.