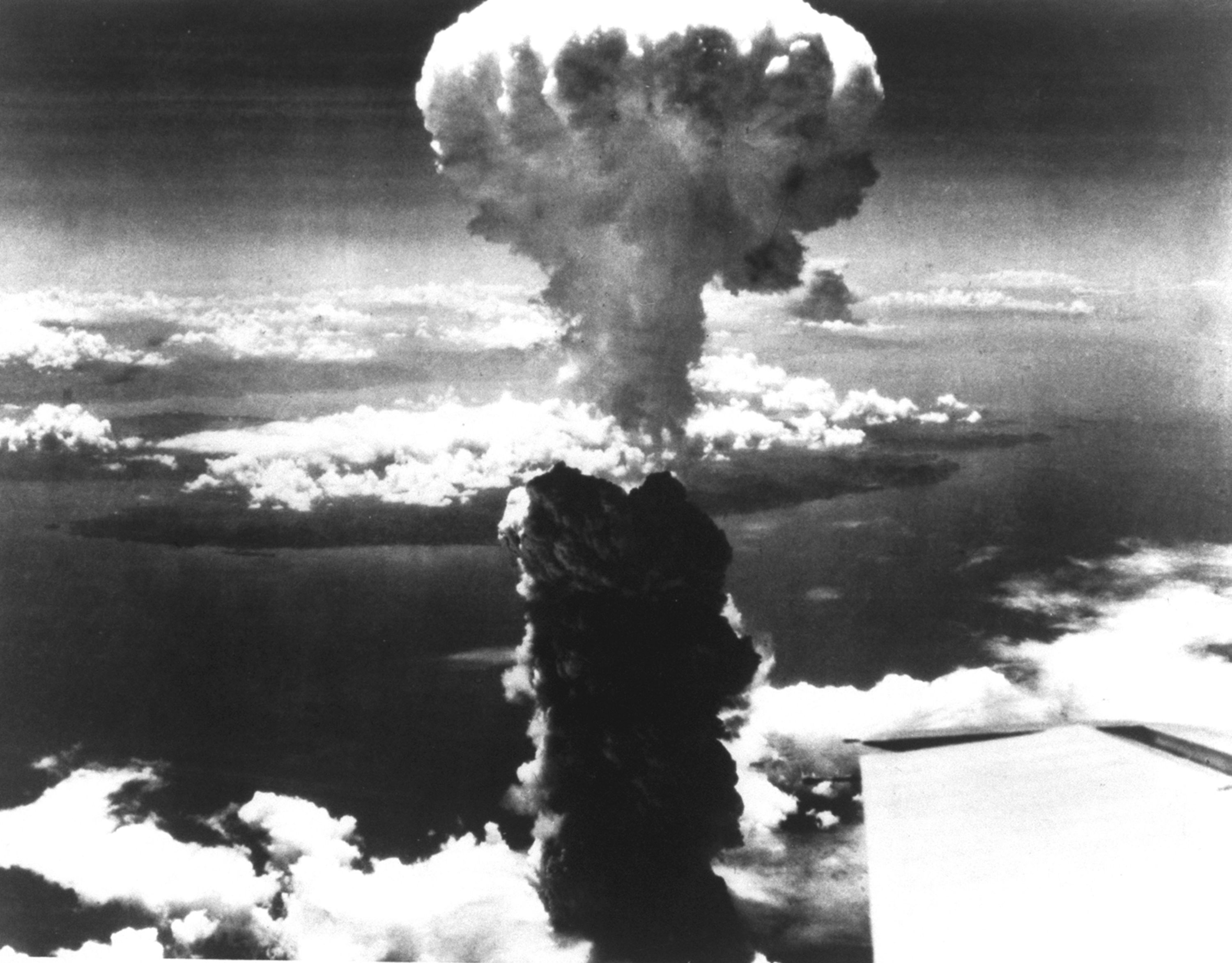

August 6, 1945. A Monday. People in Hiroshima were heading to work, clearing firebreaks, and just trying to survive a war that felt like it might never end. Then, the sky ripped open. Most of us think we know this story because we saw a black-and-white photo of a mushroom cloud in a high school textbook, but the reality of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a lot messier, more terrifying, and more politically complicated than the "it ended the war" narrative we're usually fed.

It wasn't just about a bomb. It was about a total shift in how humans treat other humans.

When the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay released "Little Boy" over Hiroshima, it used a uranium-235 core. It didn't even hit the ground. It exploded about 1,900 feet above the Shima Surgical Hospital to maximize the blast radius. Honestly, the numbers are hard to wrap your head around. Around 70,000 to 80,000 people died instantly. Not just soldiers. Mostly civilians. Imagine a flash so bright it sears the pattern of a woman's kimono onto her skin. That actually happened.

Why Hiroshima? Why Nagasaki?

People often ask why these specific cities were picked. It wasn't random. The Target Committee in Washington had a checklist. They wanted cities that hadn't been firebombed yet so they could accurately measure the "damage" of this new toy. Hiroshima was a major military hub, sure, but it was also a compact city where the hills would focus the blast.

Then there’s Nagasaki. Three days later.

Nagasaki wasn't even the primary target for the second mission on August 9. It was Kokura. But the B-29, named Bockscar, ran into thick clouds and smoke from a previous firebombing raid on nearby Yahata. The pilot, Charles Sweeney, circled three times, burning fuel, before pivoting to the secondary target. Nagasaki was a nightmare of a target—a city built in deep valleys. When "Fat Man," a plutonium implosion-type bomb, dropped, the hills actually muffled the blast for some, but for those in the Urayami Valley, it was total annihilation.

📖 Related: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

The "End of the War" Argument is Complicated

You’ve probably heard that the bombs were a "necessary evil" to prevent Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan that supposedly would have cost a million American lives. That's the standard line. But if you look at the declassified memos from leaders like Admiral William Leahy—Truman’s Chief of Staff—he was pretty blunt. He called the bomb a "barbarous weapon" and argued Japan was already defeated.

The Soviet factor is huge here. On August 8, between the two bombings, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and steamrolled through Manchuria. Many historians, like Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, argue that the Red Army’s entry scared the Japanese leadership way more than the atomic bombs did. They knew they couldn't fight a two-front war.

The US wanted the war over fast. Not just to save lives, but to keep Stalin from getting a seat at the table in the Pacific.

It’s kind of wild how much the narrative has been smoothed over. We like clean stories. "We dropped the bomb, they surrendered, peace happened." But Japan’s Supreme Council for the Direction of the War was actually split 3-3 on surrender even after Nagasaki. It took Emperor Hirohito’s personal intervention—the "Sacred Decision"—to break the tie.

The Aftermath Nobody Talked About

Radiation was a "new" kind of horror. At first, US officials basically tried to downplay it. General Leslie Groves, who headed the Manhattan Project, told Congress that dying from radiation was "a very pleasant way to die."

👉 See also: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

Yeah, right.

The Hibakusha—the survivors—dealt with keloid scars, leukemia, and "A-bomb disease" for decades. They were also socially ostracized. People were afraid radiation was contagious or that it would cause birth defects, so Hibakusha often struggled to find spouses or jobs.

- The Black Rain: After the explosions, carbon residue and radioactive dust mixed with water vapor. It fell as a thick, oily black rain. People, thirsty from the heat, drank it. It was a death sentence.

- The Shadow People: The heat was so intense it bleached everything except where a human body blocked the light, leaving permanent "shadows" on stone steps.

- Medical Chaos: In Hiroshima, 90% of the city’s doctors and nurses were killed or injured instantly because the hospitals were in the blast zone.

The Legacy We Live With

We are still living in the world created by the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It started the nuclear arms race. It created the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

Some people argue the bombs saved lives by ending the war in August rather than 1946. Others look at the 200,000+ dead civilians and see a war crime. There isn't a simple "correct" answer that makes everyone feel good. It's a heavy, dark part of our history that demands we look at it without the rose-colored glasses of "the good war."

If you really want to understand the human side, you have to read Hiroshima by John Hersey. He followed six survivors. It was published in 1946 and it’s the reason the American public stopped seeing the bomb as just a "big explosion" and started seeing it as a human catastrophe.

✨ Don't miss: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

Actionable Steps to Understand This History Better

If you want to move beyond the surface-level history of the atomic age, stop looking at just the military stats. History is lived by people, not just planned by generals in rooms.

1. Research the Franck Report

Before the bombs were dropped, a group of Manhattan Project scientists actually petitioned the Secretary of War. They argued that the US shouldn't use the bomb on a city without a demonstration first. It’s a fascinating look at the ethics of the people who actually built the thing.

2. Visit the Virtual Museums

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum has incredible online archives. Seeing the "lunchbox of Shinichi Tetsutani"—a charred container of burnt rice—is more impactful than any casualty chart you'll ever find in a textbook.

3. Study the Soviet-Japanese War of 1945

To get the full picture of why Japan surrendered, you have to look at the invasion of Manchuria. It changed the geopolitical landscape of Asia more than the bombs did in some ways, and it’s often ignored in Western education.

4. Track the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

See where we stand today. There are still thousands of nuclear warheads on hair-trigger alert. Understanding the 1945 bombings is the only way to understand why the current global tension over nuclear weapons matters so much.

The events of August 1945 weren't just the end of World War II. They were the beginning of an era where humanity finally figured out how to end itself. Staying informed about the nuances of that decision isn't just a history lesson; it's a requirement for being a responsible citizen in a nuclear-armed world.