He wasn't a professional. That’s the first thing you have to understand about Donald Crowhurst. He was an electronics engineer, a father, and a man whose business was bleeding cash. When the Sunday Times announced the Golden Globe Race in 1968—a non-stop, solo circumnavigation of the globe—Crowhurst saw a way out. He saw a hero's welcome and a fat check. Instead, he found a watery grave and a legacy defined by one of the most elaborate deceptions in maritime history.

The sea doesn't care about your mortgage. It doesn't care about your ego.

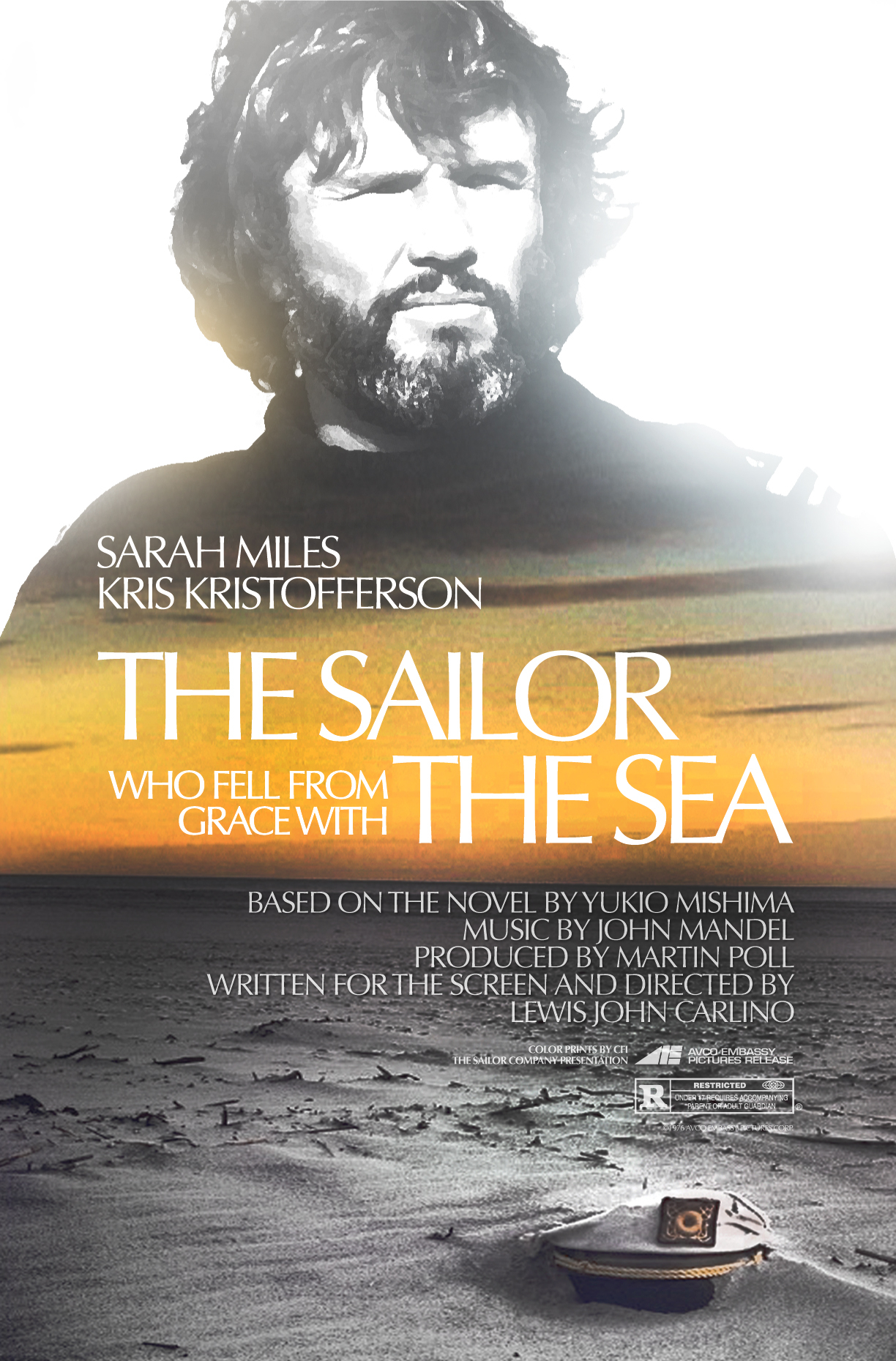

Donald Crowhurst is the ultimate "sailor who fell from grace" because his fall wasn't just physical. It was a slow, agonizing disintegration of the mind. People often ask if he was a villain. Honestly? He was probably just a man who got in too deep and couldn't find a way to admit he’d failed.

The Teignmouth Electron: A Boat Not Ready for the Southern Ocean

Crowhurst’s vessel, the Teignmouth Electron, was a 41-foot trimaran. Trimarans were relatively new to the racing world back then. They were fast, sure, but they were also notoriously unstable in the kind of monstrous swells you find in the Roaring Forties.

He was late.

The race rules stated contestants had to depart between June 1 and October 31. Crowhurst scrambled. He was literally still bolting equipment to the deck as he towed the boat out on the final possible day, October 31, 1968. He left behind a mounting pile of debt and a life insurance policy that wouldn't pay out if he quit the race early. He was trapped before he even hit open water.

Within weeks, the boat was falling apart. The screws were backing out. The hatches leaked. He realized quite quickly that if he actually tried to sail into the Southern Ocean, the Teignmouth Electron would become a coffin.

So he started writing.

👉 See also: Ohio State Football All White Uniforms: Why the Icy Look Always Sparks a Debate

The Two Logbooks: How the Hoax Began

This is where it gets weird. Most people who cheat do it for a quick gain. Crowhurst cheated to survive the shame of returning home.

He began keeping two separate logbooks. One was the "real" log, documenting his actual, lackluster progress as he drifted around the South Atlantic. The other was the "fake" log—a masterpiece of navigation and mathematical fiction. He calculated where he would be if he were actually the fastest sailor in the world. He was basically doing high-level trigonometry to lie to the entire planet.

He started radioing in record-breaking speeds.

Back in England, the press went wild. His publicist, Rodney Hallworth, fed the frenzy. Crowhurst became a national sensation. "The mystery man is winning!" the headlines screamed. But Crowhurst was actually just sitting off the coast of South America, hiding in a patch of calm water, waiting for the other contestants to loop around the world so he could "join" the pack on the way back to the finish line.

It was a brilliant plan until it worked too well.

The Mental Collapse in the Atlantic

You can't live a lie for months in total isolation without something breaking. For Crowhurst, it was his sanity.

By the time the other racers like Robin Knox-Johnston and Bernard Moitessier were making their way back up the Atlantic, Crowhurst realized he was in a terrifying position. If he won the race—which his fake coordinates suggested he might—his logbooks would be scrutinized by experts. They’d see the inconsistencies. The math wouldn't hold up under the gaze of a Royal Navy navigator.

✨ Don't miss: Who Won the Golf Tournament This Weekend: Richard T. Lee and the 2026 Season Kickoff

He was terrified of the humiliation.

His logs shifted from navigational data to 25,000 words of rambling, philosophical madness. He started writing about "cosmic integrity" and the "relativity of time." He believed he was becoming a sort of god-man who could transcend the physical world.

It’s heartbreaking, really.

The last entry in his logbook is dated July 1, 1969. It reads: "It is finished—It is finished—IT IS THE MERCY."

On July 10, the Teignmouth Electron was found drifting, ghost-like, in the mid-Atlantic. The boat was fine. The meals were half-eaten. But Donald Crowhurst was gone. He had likely stepped off the back of the boat, clutching his fake logbook, choosing the ocean over the shame of the truth.

Why the Crowhurst Story Still Haunts Us

We live in an era of curated lives. Social media is basically a digital version of Crowhurst’s fake logbook. We post the highlights and hide the leaks.

That’s why this story resonates. Crowhurst wasn't a career criminal. He was a guy who made a small lie to cover a small failure, and then had to make a bigger lie to cover the first one. Eventually, the lies became a mountain he couldn't climb over.

🔗 Read more: The Truth About the Memphis Grizzlies Record 2025: Why the Standings Don't Tell the Whole Story

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, the man who actually won the race and became the first person to sail solo non-stop around the world, showed incredible class afterward. He donated his £5,000 prize money to Crowhurst's widow and children. He knew, perhaps better than anyone, what that kind of isolation does to a person.

Misconceptions About the Voyage

- He was a total amateur: Not true. He was a skilled navigator and an inventor. He just didn't have the "blue water" experience needed for the Southern Ocean.

- The boat was a junk pile: It wasn't junk, but it was unfinished. Trimarans of that era were experimental.

- He wanted to win the money: Initially, yes. But toward the end, he was actually trying to slow down so he wouldn't finish first and face the logbook audit.

Lessons from the Fall of Donald Crowhurst

If you're looking for a takeaway from this tragedy, it’s about the cost of "sunk cost" thinking. Crowhurst felt he couldn't turn back because of the financial and social stakes.

- Acknowledge the "Point of No Return" is usually an illusion. You can almost always turn back, admit the mistake, and survive. The shame of a failed business is nothing compared to the loss of a life.

- Isolation amplifies delusion. If you’re struggling with a massive burden, total secrecy is your worst enemy. Crowhurst had no one to tell him, "Donald, it's just a boat race. Come home."

- Integrity is a survival tool. When Crowhurst lost his "cosmic integrity," as he called it, he lost his grip on reality itself.

The Teignmouth Electron eventually ended up on a beach in Cayman Brac, decaying in the sun. It’s a rusted skeleton now, a weird tourist spot for those who know the story. It serves as a stark reminder of what happens when the pressure to succeed outweighs the courage to be honest.

If you want to understand the full technical breakdown of his navigational errors, the book The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall is the definitive source. They had access to the actual logs found on the boat. It’s a chilling read, but it’s the only way to truly see the map of a mind coming apart at the seams.

Avoid the romanticized versions. Stick to the logs. The truth is much more haunting than the fiction.

Actionable Next Steps

For those interested in the psychology of high-stakes failure or maritime history, your next move should be to examine the primary source materials.

- Research the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race entries. Compare Crowhurst's reported "daily runs" against the actual capabilities of 1960s trimarans. This reveals the sheer audacity of his claims.

- Study the "Sunk Cost Fallacy." Use Crowhurst as a case study to identify moments in your own professional or personal life where you may be "doubling down" on a failing path simply because you’ve already invested time or ego.

- Visit the digital archives of the Teignmouth Electron. Seeing the photos of the abandoned cabin provides a visceral understanding of his isolation that text simply cannot convey.