You're standing on a beach. The wind is screaming. The ocean looks like it’s boiling over, and the pressure in your ears is doing that weird popping thing it does right before a massive storm hits. If you are in Miami, you call it a hurricane. If you’re in Tokyo, it’s a typhoon. And if you’re in Perth? It’s a cyclone.

They are the same thing.

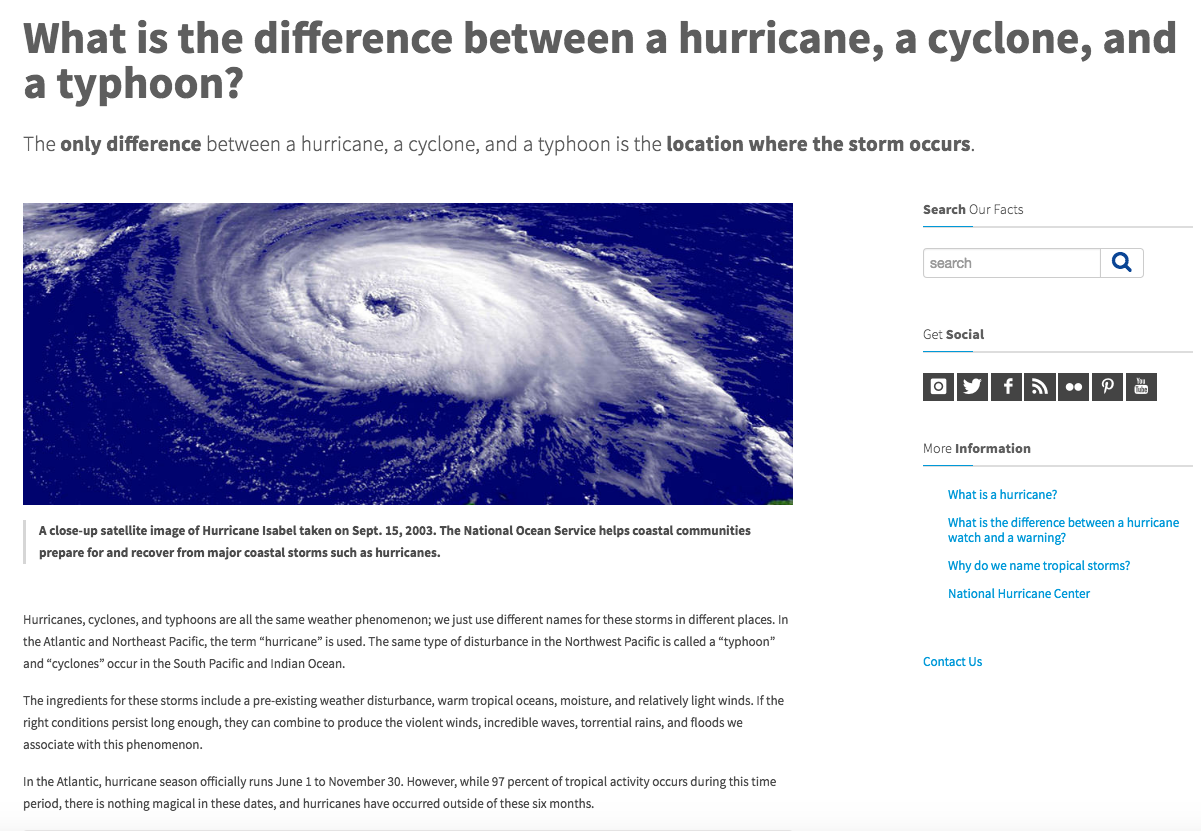

Honestly, it’s one of the most confusing bits of geographic trivia out there. We use different words for the exact same atmospheric engine. It’s a giant, rotating system of clouds and thunderstorms that forms over tropical or subtropical waters. Meteorologists call them "tropical cyclones" when they want to be precise, but for the rest of us, the difference between a hurricane cyclone and typhoon basically boils down to where you are standing when the roof blows off.

The Secret is the Longitude

It's all about the map.

In the North Atlantic, the central and eastern North Pacific, and the Caribbean, we use the term "hurricane." This name actually comes from "Huracan," a Mayan deity of wind and storm, which the Spanish eventually turned into huracán. If you live in New Orleans or New York, you are in hurricane territory.

Cross the International Date Line into the western North Pacific, and the name flips. Now it’s a typhoon. The word likely comes from the Chinese tai fung (great wind) or the Arabic tūfān. This covers places like Japan, the Philippines, and China. Same wind, same rain, different dictionary.

Then you have the "cyclone" label, which is the catch-all for everything else. This includes the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean. If a storm hits India or Australia, it’s a cyclone.

Wait. It gets slightly more annoying.

In the Southern Hemisphere, these storms rotate clockwise because of the Coriolis effect. In the Northern Hemisphere, they spin counter-clockwise. So, while a hurricane in Florida and a cyclone in Australia are technically the same "engine," they are literally spinning in opposite directions. Physics is weird like that.

Why the Nomenclature Actually Matters

You might think this is just semantics. It isn't. Because these regions are governed by different meteorological organizations, the way they measure intensity varies. This makes comparing a typhoon to a hurricane surprisingly difficult for the average person.

📖 Related: Fire in Idyllwild California: What Most People Get Wrong

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) in the U.S. uses a 1-minute sustained wind speed to categorize storms. However, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) standard—used by many agencies in the Pacific—often relies on a 10-minute average.

Ten minutes. That is a long time for a wind gust to stay steady.

Because of this, a "10-minute sustained wind" usually looks lower than a "1-minute sustained wind." If you see a typhoon and a hurricane that both look identical on satellite, the hurricane might be ranked as a Category 4 while the typhoon is called a Category 3, simply because of how the math is done. It’s like measuring a room in feet versus meters; the room stays the same size, but the number on the tape measure changes.

The Ingredients for the Perfect Storm

Whatever you call them, they all need the same three things to survive. First, warm water. We’re talking at least 80°F (about 26.5°C) extending down to a depth of about 150 feet. This water acts as the fuel. The storm sucks up the heat energy, which then fuels the convection.

Second, you need low vertical wind shear. This is basically a fancy way of saying the wind needs to be consistent from the ocean surface all the way up into the atmosphere. If the winds at the top are blowing in a different direction than the winds at the bottom, they’ll "tilt" the storm and rip it apart before it can get organized.

Third, you need the Coriolis force. This is why you don't see hurricanes forming right on the equator. Within about 5 degrees of the equator, the earth’s rotation doesn't provide enough "spin" to get the storm turning.

The Difference Between a Hurricane Cyclone and Typhoon in Terms of Damage

Is a typhoon more dangerous than a hurricane?

Statistically, the Western Pacific is the most active basin on Earth. Typhoons happen more often than hurricanes, and they often get much, much bigger. Because the Pacific is so vast and the water is so warm, storms have more time to grow before they hit land.

Super Typhoon Tip in 1979 remains the largest tropical cyclone ever recorded. Its diameter was nearly 1,380 miles. For context, if you placed that over the United States, it would stretch from New York City to Dallas.

👉 See also: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

But "dangerous" is a relative term. A small hurricane hitting a densely populated, low-lying area like New Orleans (Hurricane Katrina) or a storm hitting a region with poor infrastructure like Myanmar (Cyclone Nargis) will always be more "dangerous" in terms of human life than a massive Super Typhoon hitting a well-prepared, mountainous region of Japan.

The real killer isn't the wind. It's the water.

Storm surge causes the vast majority of deaths in these events. The low pressure at the center of the storm literally pulls the ocean surface upward, and the winds push that mountain of water onto the land. In the 1970 Bhola Cyclone in Bangladesh, the surge killed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people. It remains the deadliest tropical cyclone in history.

Breaking Down the Categories

The Saffir-Simpson Scale is what we use in the Atlantic for hurricanes.

- Category 1: 74-95 mph. Your shingles might fly off.

- Category 2: 96-110 mph. Shallow trees get uprooted.

- Category 3: 111-129 mph. Major damage to homes. This is "Major Hurricane" territory.

- Category 4: 130-156 mph. Catastrophic damage. Most trees snapped.

- Category 5: 157+ mph. Total roof failure. High-fives are out of the question.

In the Pacific, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) uses the term "Super Typhoon" for storms that reach 1-minute sustained winds of 150 mph. Basically, a Super Typhoon is a very strong Category 4 or a Category 5 hurricane.

The Indian Ocean uses different terms entirely. They talk about "Severe Cyclonic Storms" and "Super Cyclonic Storms." It’s a linguistic headache, honestly. If you are tracking a storm on a global map, you have to keep a glossary handy just to know if the news anchor is talking about a breeze or a city-leveling monster.

Misconceptions That Get People Hurt

One of the biggest mistakes people make is thinking that a "tropical storm" isn't a big deal compared to a hurricane.

A tropical storm just means the winds haven't hit 74 mph yet. But wind speed has almost nothing to do with how much rain a storm carries. We saw this with Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 and several recent storms in the Gulf of Mexico. A "weak" storm can stall over a city and dump forty inches of rain in two days.

The water doesn't care what the wind speed is.

✨ Don't miss: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

Another myth is that opening your windows during a hurricane will "equalize the pressure" and save your house. Please don't do this. All you are doing is letting the wind inside so it can lift your roof off from the inside out like a giant parachute. Keep the windows shut. Better yet, board them up.

Looking Ahead: Why It's Getting More Complex

Climate change is making the difference between a hurricane cyclone and typhoon even more of a hot-button issue for scientists. While we aren't necessarily seeing more storms every year, the ones we do see are becoming more intense.

The ocean is getting warmer. Warmer water means more fuel. More fuel means rapid intensification—where a storm jumps from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in less than 24 hours. This happened with Hurricane Otis in 2023, which slammed into Acapulco as a Category 5 after being predicted as a minor storm. It caught everyone off guard because the physics of the ocean are changing faster than some of our older models can keep up with.

We are also seeing storms retain their strength longer after hitting land. In the past, the lack of warm water "fuel" would kill a storm quickly. Now, the "brown ocean effect"—where saturated, hot soil provides enough moisture to keep the storm's core alive—is allowing these systems to travel much further inland than they used to.

Essential Steps for Storm Season

If you live in a coastal area, knowing the name of the storm is the least important part of your job. Preparation is what actually keeps you alive.

First, know your elevation. Most people don't realize that being just ten feet higher can be the difference between a dry living room and a total loss. Check your local flood maps. Don't trust the "I've lived here twenty years and it's never flooded" logic. The climate doesn't care about your tenure.

Second, have a "Go Bag" that isn't just a backpack with a granola bar. You need your actual documents—deeds, insurance papers, birth certificates—in a waterproof bag. You need at least a gallon of water per person per day. And for the love of everything, get an analog, battery-powered weather radio. If the cell towers go down, your iPhone is just an expensive brick.

Third, understand the "Cone of Uncertainty." The line in the middle of the cone is not the only place the storm will go. The cone represents where the center of the storm might go 66% of the time. You can be 100 miles outside the cone and still get hit by the worst part of the storm.

Actionable Insights for the Future

To stay safe and informed during any tropical event, follow these specific protocols:

- Audit your insurance today: Standard homeowners' insurance almost never covers "rising water" (flood). You need a separate policy through the NFIP or a private insurer. There is usually a 30-day waiting period, so you can't buy it when the storm is already on the radar.

- Ignore the "Category" for rain: If the forecast says "slow-moving," ignore the wind speed. Prepare for a flood.

- Learn the local terminology: if you travel to Southeast Asia during the fall, look for "Typhoon" warnings, not hurricanes. Same level of danger, different flag.

- Secure your perimeter: In a high-wind event, your neighbor’s patio furniture becomes a missile. If a storm is 48 hours out, everything that isn't bolted down needs to go in the garage.

Whether it’s a hurricane, a typhoon, or a cyclone, the physical reality is the same: nature is moving a massive amount of energy from the ocean to the sky. Understanding the labels helps you navigate the news, but understanding the mechanics helps you survive. Keep an eye on the barometric pressure and stay off the roads when the water starts to rise.