Pip. That’s where it starts.

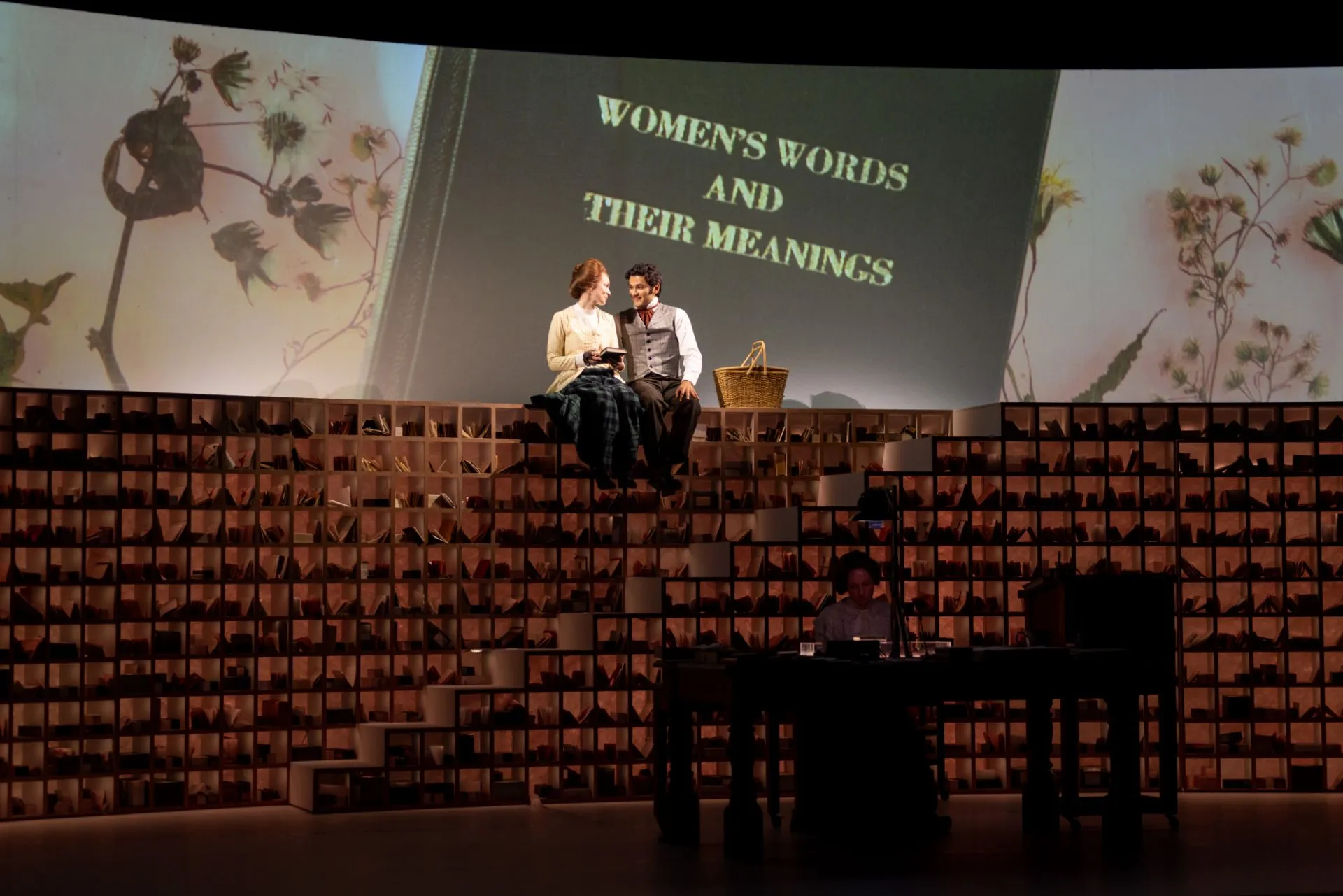

If you’ve picked up Pip Williams’ best-selling novel, The Dictionary of Lost Words, you probably realized pretty quickly that it’s not just a cozy story about a girl living under a table. It’s actually a stinging critique of how history is recorded. Words are power. But who gets to decide which words are "important" enough to make it into the official record?

The book is historical fiction, but it’s anchored in a very real, very massive project: the creation of the first Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

James Murray, the primary editor of the OED, really did work out of a "Scriptorium" in his garden. He really did have thousands of paper slips sent in by volunteers. And honestly, he really did oversee a process that was inherently biased toward the educated, the wealthy, and the male. Williams just found the gaps in that history and filled them with a character named Esme.

The Real History Behind the Scriptorium

The Scriptorium wasn't some grand library. It was a corrugated iron shed. It was freezing in the winter and stuffy in the summer.

Inside this shed, the English language was being dissected. The goal was to track the history of every single word. This meant finding the earliest usage of a word in a book and then tracking how its meaning changed over centuries. It was a Herculean task.

But here is the catch: to be included, a word needed "literary evidence."

If a word was only spoken by poor people, or if it was used primarily by women in the kitchen or the nursery, it often didn't have a written trail. It didn't exist in the eyes of the OED editors. These are the "lost words" the book title refers to. They were deemed "vulgar" or simply "unimportant."

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Take the word bondmaid. In the novel, this is the first word Esme "steals" after it falls from the sorting table. This isn't just a plot device. In the actual history of the OED, bondmaid was famously missing from the first edition. It was an accidental omission, a slip of paper lost in the shuffle. Pip Williams took that real-life mistake and turned it into a metaphor for all the women’s experiences that were being left out of the dictionary entirely.

Why We Care About "Women’s Words"

Language isn't neutral.

When you look at the early OED, the definitions for words related to women often felt clinical or dismissive. Esme, the protagonist, starts collecting words that the men in the Scriptorium reject. She talks to market sellers. She listens to servants. She records words like knackered or phrases used by suffragettes.

She realizes that by excluding these words, the editors were effectively erasing the lives of the people who used them.

Think about it. If the only words that matter are those found in "great literature," then the only people who matter are those who had the education and the leisure time to write books. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that was a very small, very specific group of men.

The Suffragette Connection

The book happens right alongside the rise of the women’s suffrage movement in the UK. This is crucial. While the men are defining words, women like Tilda (a character in the book) are out in the streets demanding the right to vote.

There is a brilliant tension here.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The dictionary is about defining the world. The suffrage movement is about changing it. Esme finds herself stuck between these two worlds. She sees that the "official" dictionary has no room for the word sisterhood in the way the suffragettes were using it.

It’s kinda wild to think that the very tools we use to communicate—our vocabulary—were shaped by such a narrow perspective. Williams forces us to ask: what else have we lost because it wasn't written down by a professor in a shed?

The Labor Nobody Talks About

We often hear about James Murray. We don't hear as much about his daughters, Rosfrith and Elsie, or his wife Ada.

In reality, the entire Murray family was involved in the dictionary. It was a family business. The children were paid small amounts to sort slips. This was grueling, repetitive work. It was the "hidden labor" that made the OED possible.

In The Dictionary of Lost Words, Esme represents this hidden labor. She is the one doing the filing, the alphabetizing, and the proofreading. She is essential, yet she is invisible to the outside world. This reflects the reality for many women of that era who were the backbone of major intellectual projects but never saw their names on the title page.

The OED took decades to finish. The first volume (A-Ant) was published in 1884. The final volume wasn't finished until 1928. By then, the world had changed completely. A world war had happened. Women had gained the vote. The "stable" language the editors tried to capture had already shifted under their feet.

Is the Dictionary Ever Truly Finished?

One of the biggest takeaways from the book is that a dictionary is a living thing. It’s not a tombstone.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Today, the Oxford English Dictionary is constantly being updated. They now look at Twitter (or X), blogs, and song lyrics to find evidence of how words are used. They’ve moved past the "literary evidence only" rule because they realize that language happens on the streets, not just in leather-bound books.

But the scars of the past are still there.

There are still debates about which words are "slang" and which are "standard." There are still arguments about who gets to be the gatekeeper of English. Pip Williams’ book resonates so much today because we are still in the middle of these linguistic power struggles. Whether it's the use of singular they or the inclusion of AAVE (African American Vernacular English) terms in the dictionary, the fight for representation in language is ongoing.

Practical Ways to Explore This Further

If you’ve finished the book and want to see the real history, there are some pretty cool things you can do.

First, look up the "Caught in the Web of Words" biography. It was written by K.M. Elisabeth Murray, who was James Murray’s granddaughter. It gives a much more factual, though still incredibly readable, account of what life was like in the Scriptorium. You’ll see that some of the "eccentric" details in the novel were actually toned down from real life.

Secondly, check out the OED’s own website regarding their history. They are surprisingly transparent about their early mistakes, including the famous missing bondmaid slip.

Thirdly, think about your own "lost words." Every family has them—words or phrases that only you use, which have deep meaning but would never be found in a dictionary.

Next Steps for the Curious:

- Visit the Oxford University Press Museum: If you’re ever in the UK, they have exhibits on the history of the dictionary, including some of the original slips and even James Murray’s velvet cap.

- Contribute to the OED: Did you know you can still help? The OED often puts out "appeals" for the earliest known use of specific words. You can be a modern-day Esme.

- Read the Companion Book: Pip Williams wrote a follow-up called The Bookbinder of Jericho. It’s set in the same world (Oxford during WWI) and explores similar themes of class, knowledge, and who gets to access it. It focuses on the women who actually bound the books that the men were writing.

Language is a map of where we've been. If the map is missing half the landmarks, we’re all a little bit lost. Understanding the history of The Dictionary of Lost Words helps us start filling in those blank spaces.