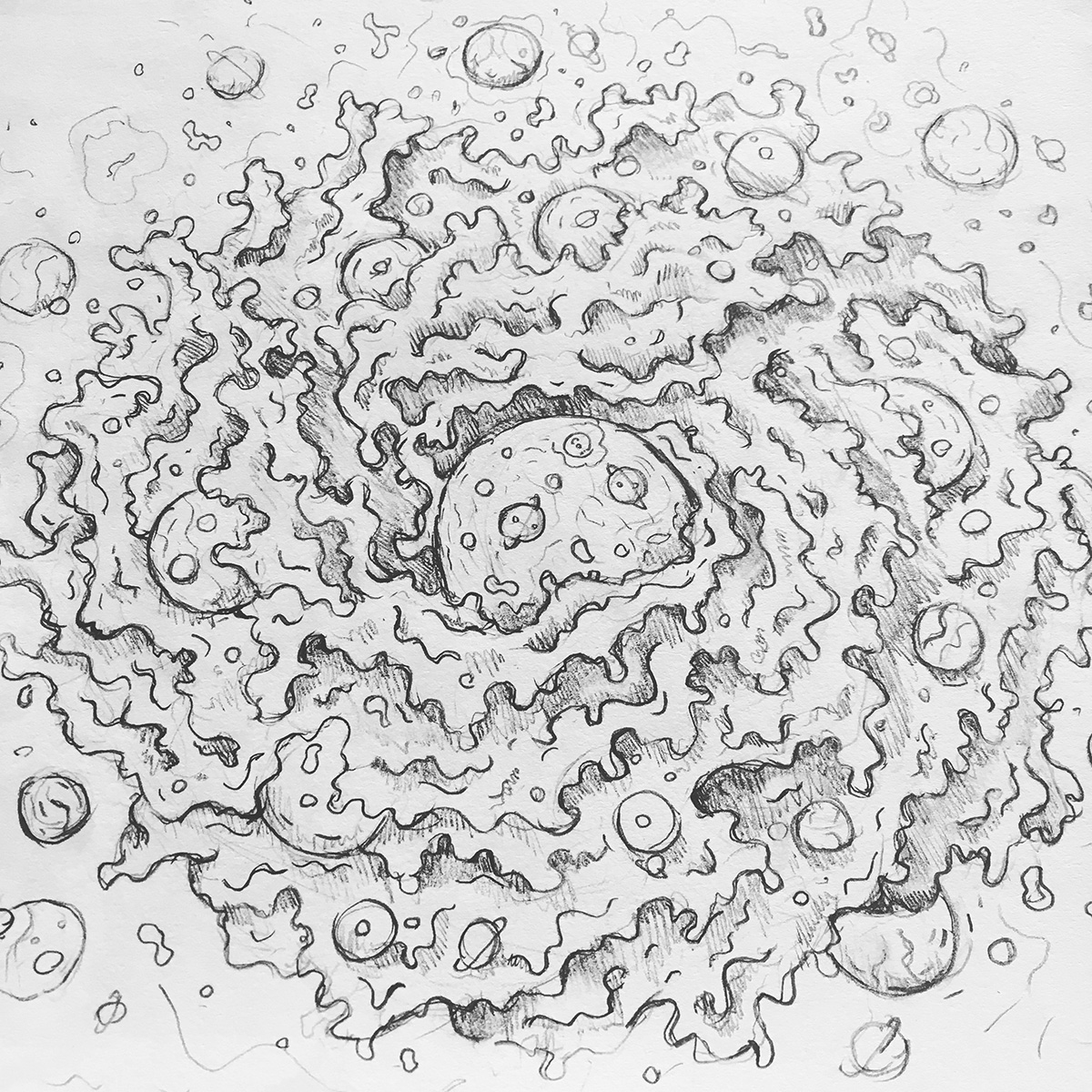

Space is big. Really big. You’ve probably seen a diagram of Milky Way structures in a textbook or on a poster and thought, "Cool, that's where I live." But here's the kicker: we have never actually seen our galaxy from the outside. Not once. Every single "photo" you see of the Milky Way as a whole is either a painting, a digital rendering, or another galaxy (usually Andromeda) standing in as a body double.

It's basically like trying to draw a map of your entire house without ever leaving the walk-in closet. You can peek through the keyhole, hear the hum of the fridge, and maybe smell what’s cooking in the kitchen, but you’re mostly guessing the layout based on echoes and shadows.

Astronomers are basically the ultimate detectives. They use radio waves, infrared light, and the way stars wobble to piece together a map that we are constantly redrawing. Honestly, it’s a bit of a mess.

Why Your Old Diagram of Milky Way is Outdated

For decades, we thought our home was a classic four-armed spiral. Simple. Elegant. Symmetrical. Then, in the mid-2000s, data from the Spitzer Space Telescope basically flipped the table. It turned out the Milky Way isn't just a swirl; it’s a barred spiral.

This means there’s a massive, chunky bar of stars running through the center. This bar acts like a giant celestial stirrer, flinging gas and dust outward and feeding the supermassive black hole at the core, Sagittarius A*. If your diagram of Milky Way features doesn't show a prominent central bar, it’s basically a relic from the 90s.

🔗 Read more: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

Recent mapping by the Gaia mission—a European Space Agency project that is currently tracking over a billion stars—revealed that the galaxy isn't even flat. It’s warped. Think of a vinyl record left in a hot car. One side curves up, the other curves down. This "warp" is likely caused by the gravitational tug-of-war with smaller satellite galaxies like the Magellanic Clouds.

The Arm Mystery: Two or Four?

This is where the experts start arguing at conferences. Most modern reconstructions show two major arms—the Scutum-Centaurus and Perseus arms—which are packed thick with stars. Then you have the "minor" arms, like the Sagittarius and Local arms.

We live in the Local Arm (or the Orion Spur). For a long time, we thought this was just a tiny bridge between bigger structures. However, newer data suggests the Orion Spur might be much more significant than we gave it credit for. It’s not just a backroad; it’s more like a major highway offramp.

Mapping the Unmappable

How do you map something you're stuck inside of? You look for "standard candles." These are objects with a known brightness, like Cepheid variables or masers (basically naturally occurring microwave lasers in space).

💡 You might also like: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

By measuring how faint these objects appear, we can calculate exactly how far away they are. Dr. Mark Reid at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics has spent years using the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) to do exactly this. His work has fundamentally reshaped the diagram of Milky Way proportions, showing that the galaxy is actually spinning faster and is more massive than we previously calculated.

- The Galactic Bulge: A dense, peanut-shaped heart of old stars.

- The Galactic Disk: Where the party happens—stars, gas, and us.

- The Halo: A massive, invisible sphere of dark matter and ancient star clusters (globular clusters) that surrounds everything else.

The halo is particularly weird because it contains "stellar streams"—ribbons of stars left over from smaller galaxies that the Milky Way literally ate. Our galaxy is a cannibal. It's currently in the middle of digesting the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy.

The Dark Matter Problem

If you look at a visual diagram of Milky Way components, you're only seeing about 5% of what's actually there. The rest is dark matter. We can't see it, touch it, or detect it with radio waves, but we know it's there because the outer stars are orbiting way too fast.

Without the "glue" of dark matter, the Milky Way would fly apart like a broken merry-go-round. Every map we draw is essentially just the foam on top of a very deep, dark ocean. When you look at the beautiful spiral arms, you're looking at density waves. Stars don't stay in the arms forever; they move in and out of them, like cars passing through a traffic jam. The arms themselves are just areas where stuff gets bunched up.

📖 Related: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

How to Read a Modern Galactic Map

If you want to find a truly accurate representation, look for the Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3) visualizations. These aren't just pretty pictures; they are coordinate-based plots of actual stellar positions.

- Look for the Bar: If the center is a perfect circle, ignore it. It needs to be elongated.

- Check the Sun's Position: We are about 26,000 light-years from the center. Not the edge, not the middle. We're in the suburbs.

- Find the Spur: Ensure the Orion Spur is represented between the Sagittarius and Perseus arms.

- Acknowledge the Warp: The best 3D models will show that "S" shape curve in the disk.

The reality is that our understanding changes every few years. In 2026, we are still processing the sheer volume of data from the James Webb Space Telescope, which is peering through the dust clouds that block our view of the "Far Side" of the galaxy. We know more about distant quasars billions of light-years away than we do about some regions on the opposite side of our own galactic center because the dust is just that thick.

Actionable Next Steps for Space Enthusiasts

Stop looking at static posters and start using dynamic tools. To truly understand the 3D layout of our home, download Gaia Sky. It’s an open-source, real-time astronomy visualization software that uses actual satellite data to let you fly through a 3D diagram of Milky Way space.

Alternatively, use the ESASky web interface to toggle between different wavelengths. Switching from "Visible" to "Infrared" will show you exactly why mapping the galaxy is so hard—the "visible" Milky Way is mostly shadows, while the infrared view reveals the glowing heat of the stars hidden behind the dust.

If you're buying a map for a classroom or your wall, look for "2020 or later" publication dates. Anything older is likely missing the barred-spiral geometry or the correct mass estimates for the dark matter halo. Real science is a work in progress, and your map should be too.