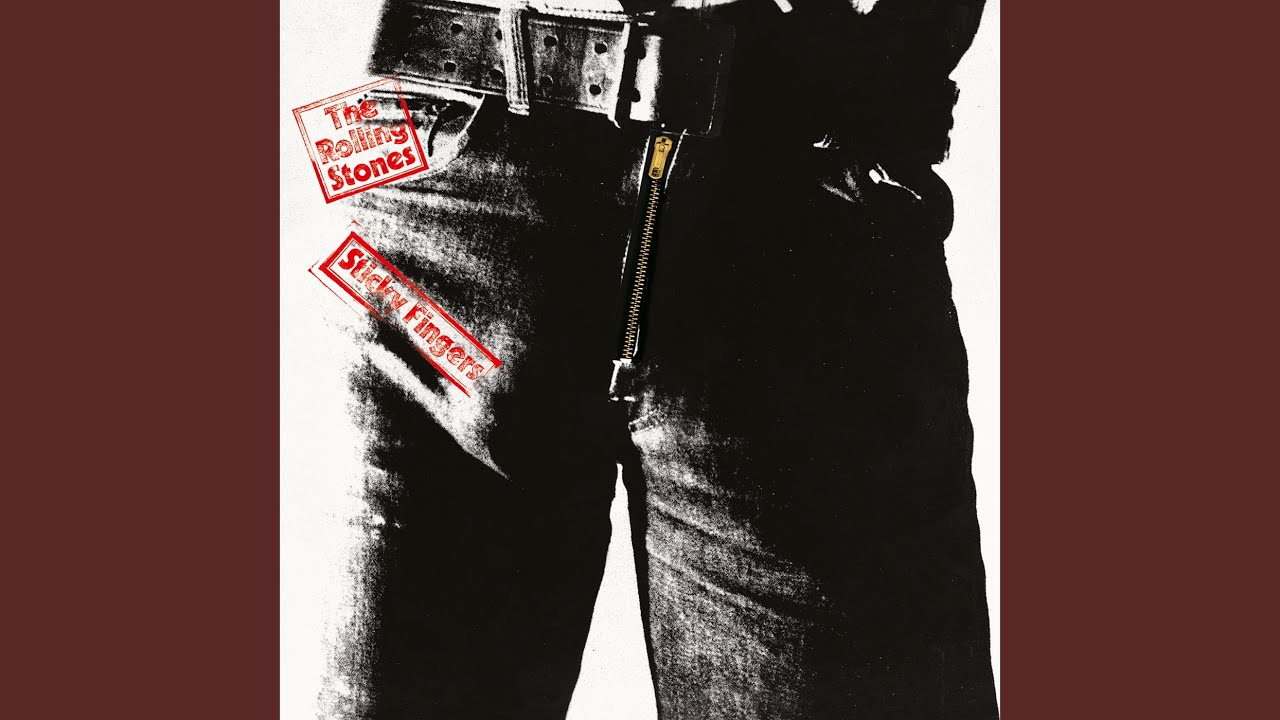

When people talk about the greatest blues-rock covers in history, they usually point to something loud. Something with screaming feedback. But on the Rolling Stones’ 1971 masterpiece Sticky Fingers, there is this haunting, acoustic slide-guitar track called You Gotta Move that feels like it was recorded in a shack in 1930 rather than a high-end studio in Alabama. It’s raw. It’s skeletal. Honestly, it’s one of the most honest moments in the Stones’ entire discography because it doesn't try to be "rock." It just tries to be the blues.

The Muscle Shoals Magic Behind You Gotta Move

The Stones didn't record this in London. They went to the source. In December 1969, right in the middle of a chaotic American tour, the band pulled into Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama. This wasn't some corporate junket. It was a pilgrimage. If you watch the documentary Gimme Shelter, you can actually see them huddled in that cramped room, listening back to the playback of You Gotta Move. They look exhausted. They look like they’ve seen too much.

Keith Richards is playing a 1930s National Steel guitar. You can hear the metal resonator vibrating against his chest. Mick Jagger isn't doing his stadium strut here; he’s doing a low, guttural moan that sounds surprisingly close to a field holler. It’s a song about the inevitability of death and judgment. "You may be high, you may be low," the lyrics go. It doesn't matter who you are. When the Lord gets ready, you gotta move.

The track was basically a way for the band to decompress. After the psychedelic experimentation of the late 60s and the looming shadow of the Altamont tragedy, the Stones needed to find their feet again. They found them in the dirt of the Mississippi Delta.

Who Actually Wrote It?

A lot of casual fans think the Stones wrote this. They didn't. This is a traditional African American spiritual that had been floating around the South for decades before a man named Fred McDowell—better known as Mississippi Fred McDowell—recorded the definitive version in 1964.

McDowell was a "discovery" of the folk-blues revival. He didn't pick up a guitar to get famous; he played because he had to. His style was "straight-line" blues. No fancy chord changes. Just a relentless, hypnotic drone. When the Rolling Stones covered You Gotta Move, they were paying direct homage to McDowell’s version.

The Fred McDowell Connection

McDowell was famously quoted as saying, "I do not play no rock and roll." He was a purist. Yet, he liked the Stones. He liked that they brought his music to a younger audience. The royalties from the Stones' version of You Gotta Move actually helped McDowell in his final years. It’s a rare case where a British Invasion cover actually benefited the original artist in a tangible way.

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The song itself is built on a simple structure:

- A call-and-response rhythm that mirrors church congregations.

- A sliding riff that mimics the human voice.

- Lyrics that emphasize spiritual equality—death as the great equalizer.

Why the Sticky Fingers Version Hits Different

If you listen to the track on Sticky Fingers, there is a weird, dragging tempo. It feels heavy. Bill Wyman’s bass is thick, and Charlie Watts isn't playing a standard 4/4 rock beat. He’s hitting the snare like he’s hammering a nail into wood.

Most rock bands at the time were trying to make the blues "heavy" by adding distortion. The Stones did the opposite. They made it heavy by stripping it down to the bone. Mick Taylor’s slide guitar work is understated but surgical. It’s the sound of a band that finally stopped trying to imitate their idols and started feeling the music instead.

It’s also worth noting the placement on the album. You Gotta Move sits right after "Can't You Hear Me Knocking," which is this sprawling, seven-minute jazz-rock fusion jam. To go from that level of technical complexity to a three-chord blues spiritual is a total 180-degree turn. It’s a palette cleanser. It reminds the listener that no matter how far the Stones strayed into celebrity and decadence, they were still just kids who loved Chess Records.

The Live Evolution: From Acoustic to Electric

The Stones didn't just leave the song in the studio. It became a staple of their 1969 and 1971 tours. If you look up the Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out! era performances, the song takes on a different energy. On stage, Jagger would often use it as a moment of theatricality.

But even then, the core of the song remained untouchable. You can’t "rock up" a song like You Gotta Move without losing the point. It’s a song about humility. It’s about the fact that you can have all the money and fame in the world, but when the time comes to "move," you have no choice.

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Key Versions to Compare

- Mississippi Fred McDowell (1964): The blueprint. Brutal, rhythmic, and haunting.

- The Rolling Stones (1971): The most famous version. A masterclass in atmosphere.

- The Soul Stirrers (1950s): A gospel version that shows where the melody actually came from before it hit the blues circuit.

- Aerosmith (2004): A much louder, more aggressive take from their Honkin' on Bobo album.

Honestly, the Aerosmith version is fine, but it lacks the dread of the Stones' recording. The Stones' version feels like it was recorded at midnight in a graveyard.

The Cultural Impact and Legacy

You Gotta Move helped cement the Rolling Stones’ reputation as the premier curators of American roots music. While the Beatles were looking toward India and the avant-garde, the Stones were looking toward the American South.

This song, specifically, bridged the gap between the gospel tent and the rock arena. It showed that the "devil's music" (blues) and "God's music" (gospel) were often singing about the same thing: survival.

Even today, when the Stones play it live (which is rare now, but it happens), the crowd goes quiet. It’s a "hush" song. In a world of flashing LEDs and massive PA systems, a simple slide guitar riff about the end of life still has the power to make 50,000 people pay attention.

How to Listen Like a Pro

If you really want to appreciate what’s happening in the Stones' version of You Gotta Move, don't listen to it on your phone speakers. Get a decent pair of headphones.

- Focus on the left channel: You can hear the grit of the strings.

- Listen to Jagger’s breathing: He isn't cleaning up the vocal. You can hear him inhaling sharply between lines.

- The "thump": That isn't just a drum. It’s a collective stomp.

It’s a masterclass in "less is more." In an era where every song is compressed and auto-tuned to death, You Gotta Move stands as a reminder that imperfections are what make music human.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Actionable Insights for Blues Fans

If you want to dig deeper into the world of You Gotta Move and the Delta blues style that inspired the Rolling Stones, here is exactly how to start.

First, go find the album You Gotta Move by Mississippi Fred McDowell (Arhoolie Records). It is the "source code" for the Stones' interpretation. Pay attention to how he uses his thumb to keep a steady bass line while his fingers play the melody—it’s a technique called "alternating thumb" or "monotonic bass" that defines the North Mississippi Hill Country blues.

Next, try learning the riff. It’s traditionally played in Open D tuning (D-A-D-F#-A-D) or Open G tuning (D-G-D-G-B-D). If you have a slide, use it on your pinky or ring finger. The key to the "Stones sound" on this track isn't speed; it's the "vibrato" at the end of the slide move. You have to let the note shake slightly to get that vocal quality.

Finally, watch the Muscle Shoals footage in Gimme Shelter. It’s a rare glimpse into the creative process of a band at their absolute peak, showing that even rock gods have to submit to the power of a simple, centuries-old melody. Understand that this song isn't a cover; it’s a continuation of a long, oral tradition that the Stones were lucky enough to join.

Stay away from over-produced modern covers if you want to understand the soul of the track. Stick to the field recordings and the 1970s analog tapes. That is where the truth of the song lives.