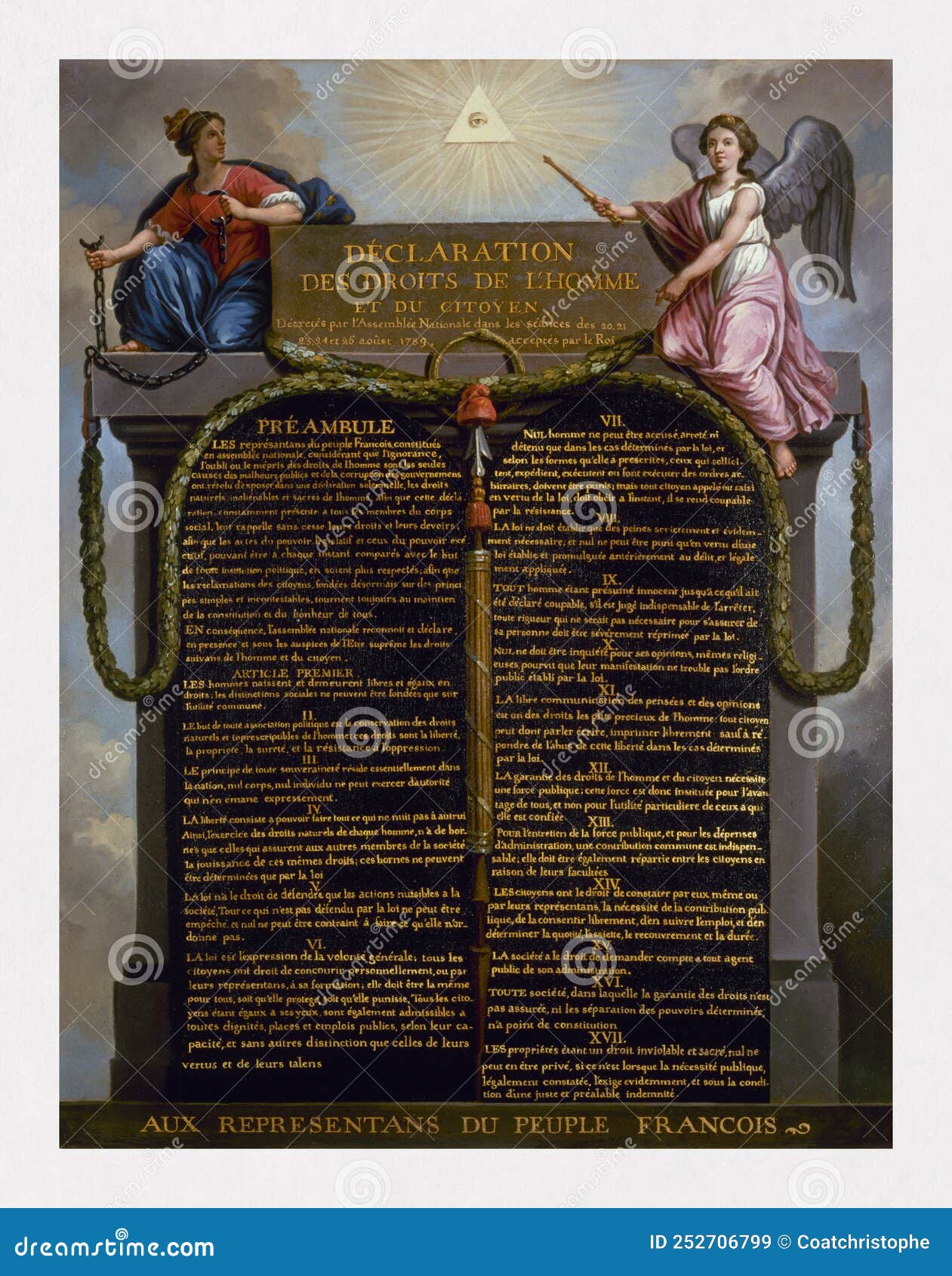

In the summer of 1789, Paris was a powder keg. People were starving, the monarchy was broke, and the old ways of doing things—where a few nobles held all the cards—were finally falling apart. On August 26, the National Constituent Assembly dropped a document that basically changed the course of human history. It’s called the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Honestly, it’s one of the gutsiest pieces of writing ever produced. It didn't just ask for better bread prices; it fundamentally redefined what it means to be a human being living in a society.

Most people think of it as just a French version of the U.S. Bill of Rights. But that’s a bit of a simplification. While the Americans were looking to protect their existing liberties from a distant king, the French were trying to blow up an entire social order and build a new one from scratch. They wanted to kill the idea that some people are born "better" than others. It was messy, it was bold, and it was incredibly dangerous.

The Chaos That Created a Masterpiece

You can’t understand the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen without realizing how desperate the situation was. France was essentially bankrupt after helping out in the American Revolution (ironic, right?). King Louis XVI was deeply out of touch. The "Third Estate"—which was basically everyone who wasn't a priest or a noble—was fed up with paying all the taxes while having zero say in how the country was run.

When they finally broke away and formed the National Assembly, they knew they needed a manifesto. They needed something that would act as a preamble to a new constitution.

Marquis de Lafayette was a key player here. He’d just come back from hanging out with Thomas Jefferson in America, and he actually brought a draft of the Declaration to Jefferson for feedback. Imagine that for a second. Two of history’s biggest political nerds sitting in a room in Paris, trying to figure out how to codify "freedom" while the city outside was on the verge of a total meltdown. They weren't just writing for France; they were writing for the world.

What the Declaration Actually Says (and What It Doesn't)

The document is pretty short—only 17 articles. But man, do they pack a punch.

✨ Don't miss: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

Article 1 is the big one: "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights." That sounds like common sense now, but in 1789? It was a revolution in a single sentence. It wiped away centuries of feudalism, serfdom, and the "divine right" of kings. Suddenly, the King wasn't the source of law; the "General Will" of the people was.

Then you have Article 2, which lists the "natural and imprescriptible" rights: liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Notice that "property" is right up there with liberty. This wasn't a communist manifesto; it was a bourgeois revolution. The people writing this were lawyers, merchants, and landowners. They wanted freedom, sure, but they also wanted to make sure their stuff was safe from the government.

The Problem of "The Citizen"

Here’s where it gets kinda complicated. The title says "Man and Citizen." To the writers, these were two different things. "Man" had natural rights just by existing. "Citizen" had political rights—like the right to vote or hold office.

The catch? Not everyone got to be a "citizen."

They divided people into "active" and "passive" citizens. If you didn't pay enough in taxes, you were a passive citizen. You had your human rights protected, but you couldn't vote. And women? They were almost entirely left out of the conversation. Olympe de Gouges, a brilliant playwright, saw this hypocrisy immediately. She wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 to point out that if women could be sent to the scaffold to be executed, they should also have the right to stand on a speaker's platform. Sadly, the revolutionaries weren't ready for that. They executed her a few years later.

🔗 Read more: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Why This Document Still Hits Hard in 2026

You might wonder why we’re still talking about a 200-year-old piece of paper. Honestly, it’s because we’re still fighting the same battles. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen introduced the idea of "presumption of innocence." That’s Article 9. Before this, if the state accused you of something, you were basically guilty until you could prove otherwise. The Declaration flipped that. It’s the reason why, in most modern democracies, the burden of proof is on the government.

It also tackled freedom of speech and religion (Articles 10 and 11). In a world where you could be thrown in the Bastille just for insulting a bishop or criticizing the King’s fashion choices, this was massive. It said that as long as your opinions don't "disturb the public order," you're free to have them.

We see the DNA of this document in:

- The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

- The European Convention on Human Rights.

- Modern constitutions from South Africa to Brazil.

The Dark Side: When Rights Lead to Terror

History isn't a fairy tale. The same people who cheered for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen eventually ended up overseeing the Reign of Terror. Maximilien Robespierre, who was a huge fan of these Enlightenment ideals, eventually decided that the only way to protect "liberty" was to execute anyone he thought was an "enemy of the people."

It’s a grim reminder that rights are just words on paper unless there’s a stable system to enforce them. The French Revolution got so caught up in the "General Will" that it forgot to protect the individual from the mob. This is a nuance often missed in history books. The Declaration was a soaring success as a statement of intent, but a tragic failure in its immediate application. It took France nearly a century and several more revolutions to actually get the balance right.

💡 You might also like: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Real-World Impact: Property and Taxation

Article 13 and 14 are surprisingly practical. They talk about taxes. In the old days, the King just took what he wanted. The Declaration changed that. It said that taxes must be "equally apportioned among all citizens according to their means." It also said that citizens have the right to know how their tax money is being spent.

If you've ever looked at a government budget or argued about tax brackets, you're essentially having a conversation that started in August 1789. The idea that the state owes the taxpayer an explanation is a direct result of these articles.

Common Misconceptions About the Declaration

- It ended the monarchy. Nope. When it was written, France was still a monarchy. The National Assembly wanted a constitutional monarchy, similar to what the UK has now. The whole "beheading the King" thing didn't happen until 1793.

- It was inspired only by the American Revolution. While Lafayette and Jefferson were tight, the French version was much more influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and his idea of the "Social Contract." The French were more obsessed with the "General Will" than the Americans, who were more focused on individual checks and balances.

- It gave everyone rights. As mentioned, it really didn't. It left out women, it was vague about slavery in French colonies (though slavery was eventually abolished, then reinstated by Napoleon, then abolished again), and it excluded the poor from political power.

How to Use This Knowledge Today

Understanding the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen isn't just for history buffs. It's a toolkit for understanding modern politics. When you hear debates about digital privacy, or whether certain types of speech should be banned online, or how high the "wealth tax" should be, you are seeing Article 2, Article 11, and Article 13 in action.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Read the original 17 articles. They are surprisingly short. Don't read a summary; read the actual text. You can find the English translation on the Avalon Project website from Yale Law School. It takes about five minutes.

- Compare it to the Bill of Rights. Look at the US Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) and the French Declaration side-by-side. You’ll notice the French version is much more philosophical, while the American one is more like a legal "to-do" list.

- Research Olympe de Gouges. If you want to see the "limitations" of the revolution, look into her life. It provides a necessary counter-perspective to the male-centric view of 1789.

- Look at modern court cases. Many international courts still cite the principles found in the Declaration when deciding on human rights abuses. Seeing how "Natural Law" is applied to 21st-century tech issues is fascinating.

The Declaration wasn't the end of the struggle for human rights—it was the starting gun. It provided the language we still use to demand justice. Even if the men who wrote it were flawed and their execution of the ideas was often bloody, the ideas themselves remain the benchmark for what a free society should look like.