You probably picture it. The quill scratching against parchment. Men in powdered wigs gathered in a stifling room in Philadelphia, sweating through their wool coats while they wait for their turn to sign a document that changed everything. It’s a great image. It’s also kinda wrong.

Most of us were taught that the Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776. It wasn't. Actually, the Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2. John Adams was so convinced July 2 would be the big holiday that he wrote home to his wife, Abigail, saying it would be celebrated with "pomp and parade" forever. He was off by two days. The actual signing? That mostly happened on August 2, and some guys didn't put pen to paper until months later.

History is messy. It’s not a clean line of events. The Declaration of Independence wasn't just a breakup letter to King George III; it was a high-stakes legal gamble that could have ended with every single signer hanging from a noose. They weren't just "founding" a country. They were committing treason.

Why the Declaration of Independence was basically a legal brief

We talk about the "spirit of '76" like it was this magical wave of emotion. In reality, Thomas Jefferson was tasked with writing what was essentially a legal justification for a divorce. He wasn't trying to be original. He even admitted later that he wasn't looking for "new principles" or "sentiments never before thought of." He was just trying to summarize the "American mind."

Jefferson leaned heavily on the ideas of John Locke, an English philosopher who had been dead for seventy years. If you look at Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, you’ll see the DNA of the Declaration. Locke talked about "life, liberty, and property." Jefferson swapped "property" for "the pursuit of happiness."

Why the change?

Some historians, like Garry Wills in Inventing America, suggest Jefferson was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment. "The pursuit of happiness" sounds airy-fairy to us now, but in 1776, it was a political statement. It meant that the government’s entire job was to ensure the well-being of the people. If the government isn't doing that, the people have a literal right to scrap it.

The middle section of the document is the part everyone skips in school. It’s a long, angry list of grievances. It’s the "He has done this" and "He has done that" section. It reads like a list of charges in a courtroom. They were documenting the "repeated injuries and usurpations" to prove to the rest of the world—specifically France and Spain—that they weren't just some rowdy rebels. They were a legitimate nation seeking international help.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The "All Men Are Created Equal" problem

Let’s be real. This is the hardest part of the document to reconcile today. How does a man like Thomas Jefferson, who enslaved over 600 people throughout his life, write that "all men are created equal"?

It’s a massive contradiction.

Some people argue that Jefferson meant "all white, land-owning men." Others say he was setting a standard he knew he couldn't personally meet but hoped the future would. There was actually a passage in the original draft that blamed King George for the slave trade. It was a weird, hypocritical move, but it was there. The Continental Congress ended up cutting it out because delegates from South Carolina and Georgia wouldn't sign if it stayed in.

This shows you that even at the birth of the country, the Declaration of Independence was a product of compromise and political maneuvering. It wasn't a perfect document handed down from a mountain. It was a compromise.

The risk you probably didn't realize

When Benjamin Franklin supposedly said, "We must all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately," he wasn't being dramatic. He was being literal.

By signing that parchment, these men were officially outlaws. They weren't just politicians; they were targets. The British didn't see them as "Founding Fathers." They saw them as criminals.

Take the case of Richard Stockton. He was a signer from New Jersey. Not long after signing, he was captured by the British, thrown into a brutal prison, and treated so poorly that his health was permanently destroyed. He was the only signer to recant his signature under duress, though he later took an oath of allegiance to New Jersey.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The cost was high.

- Carter Braxton of Virginia saw his ships swept from the seas and his fortune disappear.

- Thomas Nelson Jr. reportedly urged the militia to fire on his own home because British officers were using it as a headquarters.

- Francis Lewis had his home destroyed and his wife imprisoned.

These weren't just names on a page. They were people with everything to lose.

How the document actually traveled

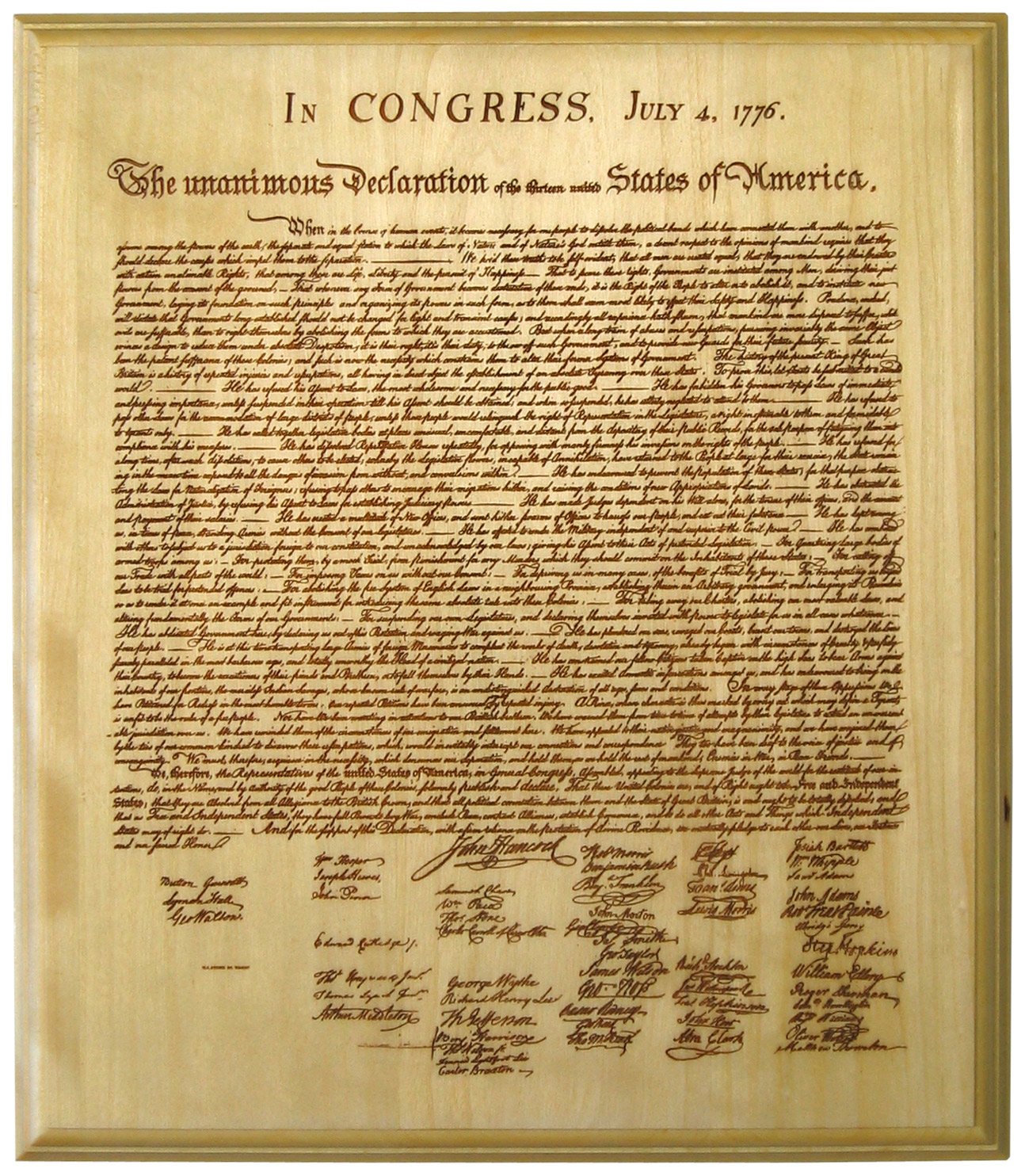

We treat the original Declaration of Independence like a holy relic now. It’s under protective glass in the National Archives, bathed in argon gas to keep it from rotting. But for years, it was treated like any other piece of paper. It was rolled up, unrolled, tucked into trunks, and moved from city to city as the Continental Congress fled the British.

During the War of 1812, when the British were busy burning Washington D.C., a clerk named Stephen Pleasonton saved the document. He stuffed it into a linen sack and hauled it away in a wagon just before the city went up in flames. If it weren't for a random government employee, the original might have been ashes two centuries ago.

That’s why the ink is so faded today. All that rolling and unrolling, plus years of being hung in direct sunlight in the 1800s, almost erased the text.

The hidden message on the back?

Sorry to disappoint the National Treasure fans, but there’s no secret map on the back of the Declaration of Independence. There is, however, a very simple note written on the bottom of the reverse side: "Original Declaration of Independence dated 4th July 1776."

It was basically a filing label.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The global impact of those words

The Declaration of Independence didn't just stay in the colonies. It went viral in an era of slow-moving ships and horses. Within weeks, it was being read in London. The British press mocked it, obviously. But in France, it was a sensation.

It helped spark the French Revolution. It inspired independence movements in Latin America. It was the blueprint for Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam and for activists in the 19th-century women's suffrage movement. When the women at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 wrote their "Declaration of Sentiments," they used Jefferson’s exact structure. They just changed it to "all men and women are created equal."

It’s a "living" document not because the laws change, but because its meaning expands.

The messy reality of July 4th

We celebrate with fireworks because the Continental Congress finally approved the final wording on July 4th. That’s the date that was printed on the "Dunlap Broadsides," the first printed copies that were rushed out to the public.

But even then, the news moved slow. George Washington didn't read the Declaration to his troops in New York until July 9. The people of Savannah, Georgia, didn't hear it until August. By the time some people were celebrating their new freedom, the war was already going badly for the Americans.

It's a reminder that declaring something doesn't make it true. You have to fight for it.

Actionable steps for history buffs

If you want to move beyond the textbook version of the Declaration of Independence, here is how you can actually engage with this history:

- Read the Grievances: Don't just read the "Life, Liberty" part. Read the 27 complaints against the King. It tells you exactly what the colonists were afraid of—things like standing armies, unfair taxes, and the suspension of local laws. It makes the document feel much more "real."

- Visit the National Archives (Virtually or In-Person): Seeing the "Handwritten" or "Engrossed" version is cool, but look at the "Dunlap Broadside" too. That was the version people actually saw in 1776. It’s cleaner and looks more like a newspaper.

- Check out the "Declaration Resources Project": Harvard University has a great project that tracks every known copy of the Declaration. It’s fascinating to see how many variations existed and where they ended up.

- Compare the Drafts: Look up Jefferson’s "Rough Draught." You can see what he crossed out and what John Adams and Benjamin Franklin changed. It’s like looking at a tracked-changes Word doc from 250 years ago.

- Explore the Signers: Pick one name at the bottom of the document that isn't Hancock, Jefferson, or Adams. Look them up. You’ll find stories of regular merchants, doctors, and farmers who decided to risk a hanging for an idea.

The Declaration of Independence wasn't the end of a process. It was a terrifying beginning. It’s a document full of contradictions, written by flawed men, but it set a standard that we are still trying to live up to today.