He was in the tub. Again.

Jean-Paul Marat wasn't exactly relaxing when Charlotte Corday walked into his apartment on July 13, 1793. He was soaking in a medicinal bath of vinegar and water, trying to soothe a skin condition that made his life a living hell. Most historians think it was dermatitis herpetiformis, though some argue for scabies or even syphilis. Honestly, the medical diagnosis matters less than the optics. To the people of Paris, he was a martyr in a bathtub. To the rest of the world, The Death of Marat became the defining image of the French Revolution’s bloody, chaotic heart.

Jacques-Louis David’s painting of the scene is everywhere. You’ve seen it on history book covers, in parodies, and probably in a Lady Gaga music video. But the painting is a lie. Well, maybe "lie" is too strong. It’s a masterpiece of propaganda. David was Marat's friend. He didn't want to show a man covered in scaly, weeping sores and surrounded by the stench of a cramped, dirty apartment. He wanted a saint.

The Woman Behind the Knife

Charlotte Corday wasn't some random assassin. She was 24, educated, and deeply political. She belonged to the Girondins, a moderate faction that was losing a very literal head-to-head battle with Marat’s radical Jacobins. Corday didn't see herself as a murderer. In her mind, she was a savior. She actually believed that by killing Marat, she would stop the "Reign of Terror" before it really got started.

"I killed one man to save 100,000," she famously said during her trial.

She bought a kitchen knife at a shop in the Palais-Royal. She took a carriage to his door. She was turned away at first. Then she wrote him a letter claiming she had names of traitors to give him. Marat, ever the paranoid journalist, couldn't resist. He let her in. While he sat there, naked and vulnerable under a sheet, writing down the names of people he planned to send to the guillotine, she plunged the knife into his chest.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

It was a single blow. It severed a major artery. He died almost instantly, calling out for his wife, Simone Évrard.

Why The Death of Marat Painting Still Matters Today

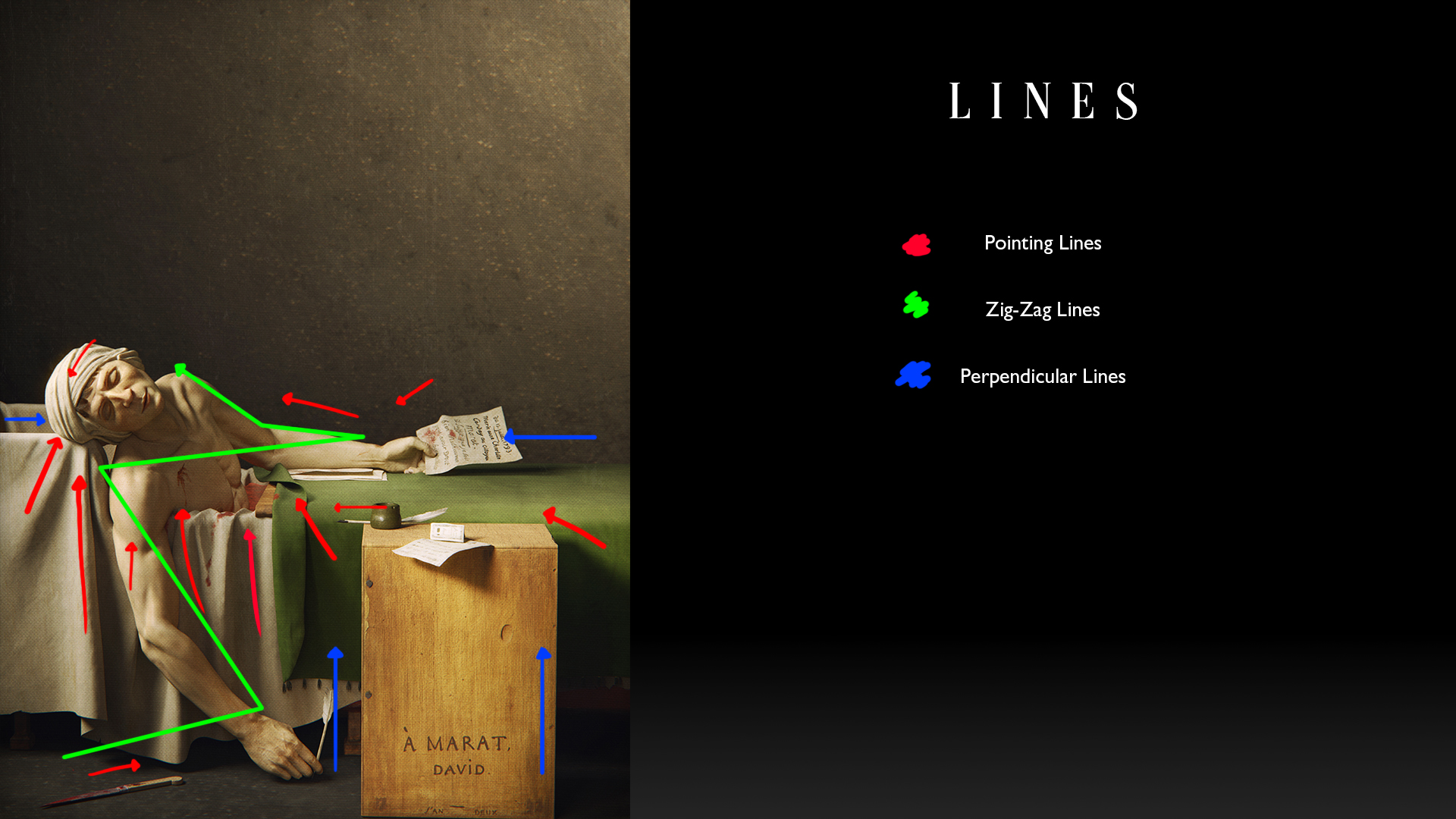

Art historians like T.J. Clark have spent decades dissecting why this specific canvas holds so much power. It’s the "Pietà" of the Revolution. David used the same lighting and body positioning that Renaissance artists used for Jesus being taken down from the cross. Look at Marat’s slumped arm. Look at the wound. It’s calculated.

The background is a dark, empty void. This forces your eyes onto Marat’s face, which looks strangely peaceful. David left out the skin disease. He left out the mess. Instead, he painted a wooden crate used as a desk, making Marat look like a man of the people who lived simply. In reality, Marat was a bit of a lightning rod for hate, even among his allies. He was a "professional agitator" before that was even a term.

The Gritty Reality vs. David’s Vision

If you could step into that room in 1793, it wouldn't look like a museum piece.

- The smell of the vinegar bath would be overwhelming.

- The room was cluttered with papers, pamphlets, and inkwells.

- Marat wore a vinegar-soaked bandana around his head to help with the itching.

- There were blood-soaked towels everywhere.

David’s version is minimalist. It’s clean. It’s the 18th-century equivalent of an Instagram filter. He even made the note Marat is holding a testament to his supposed kindness—it mentions a letter to a war widow. It's high-level spin doctoring.

👉 See also: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

The Aftermath: Did the Murder Backfire?

Corday got her wish, sort of. She was guillotined four days later. But her plan to end the violence? Total failure.

Instead of calming the waters, The Death of Marat turned a polarizing, angry journalist into a holy figure. People started praying to him. They renamed streets after him. They even renamed the Montmartre district "Montmarat" for a while. The Jacobins used his death as an excuse to ramp up the executions. If you weren't mourning Marat, you were a suspect.

The Terror didn't stop. It accelerated. Robespierre took the momentum and ran with it until he, too, lost his head. History is weird like that. The very act meant to stop a massacre became the fuel for one.

The Science of the Skin Condition

For years, people speculated about what was actually wrong with Marat. In 2019, scientists actually performed a DNA analysis on the bloodstains from the original newspapers Marat was holding when he died. They found evidence of Malassezia restricta, a fungus that causes severe skin issues. It wasn't just "stress." He was genuinely suffering, which explains why he spent 20 hours a day in that tub.

It also adds a layer of humanity to the story. Imagine trying to run a revolution while your skin feels like it's on fire. It doesn't justify the people he sent to the blade, but it makes him a person rather than just a figure in a gold frame.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

How to See it Today

The original painting by Jacques-Louis David is in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. Why Belgium? Because when Napoleon fell and the monarchy returned to France, David was exiled. He took his most famous work with him. It was too "revolutionary" to stay in Paris at the time.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're interested in the intersection of art and politics, studying the The Death of Marat is the best starting point. You can't understand modern political propaganda without looking at David’s work first.

- Visit the Site: The actual house at 30 Rue des Cordeliers was demolished in the 1870s, but you can visit the Musée Carnavalet in Paris to see Marat’s actual bathtub. It’s eerie.

- Analyze the Lighting: If you're a photographer or artist, look at "chiaroscuro." David used it to create drama. The light hits Marat, but the killer, Charlotte Corday, isn't even in the frame.

- Read the Letters: Corday’s "Address to the French people" is a fascinating look into the mind of someone who believes political violence is a moral necessity.

- Compare the Versions: David’s students made several copies. See if you can spot the differences in the ones hanging in the Louvre or at Versailles.

The story of Marat reminds us that history isn't just about what happened. It’s about who got to tell the story afterward. Corday held the knife, but David held the brush. In the long run, the brush was much more powerful.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly grasp the impact of this event, look into the DNA study published in Current Biology regarding Marat’s skin condition. It’s a rare instance where modern forensics settles an 18th-century debate. Afterward, compare David’s painting to Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry’s 1860 version, which shows Charlotte Corday as the hero and Marat as a monster. It’s a perfect lesson in how perspective changes over a century.

Check out the "Marat" section in the French National Archives online to view scans of the actual trial transcripts of Charlotte Corday. Reading her direct responses to the judges provides a chillingly clear view of her conviction and the political climate of the 1790s.