You’ve probably seen it. A man slumped over the edge of a copper bathtub, a quill still gripped in his right hand, a look of strange, eerie peace on his face. It’s Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 masterpiece. But the death of Marat meaning isn't just about a guy getting stabbed while taking a soak. It’s actually one of the most successful pieces of political "fake news" ever created.

History is messy.

Jean-Paul Marat was a doctor, a journalist, and a radical. He was also, frankly, a bit of a loose cannon who helped fuel the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. When Charlotte Corday walked into his apartment on July 13, 1793, and plunged a kitchen knife into his chest, she thought she was saving France. David, his friend and a fellow revolutionary, had a different idea. He wanted to turn a controversial, skin-diseased politician into a secular saint.

The Death of Marat Meaning and the Art of the Spin

David was the ultimate image-maker. Think of him as the Chief Brand Officer for the French Revolution. When he painted this, he wasn't trying to show exactly what happened. He was trying to make you feel something.

Look at the lighting. It’s dramatic. It’s dark. It looks a lot like Caravaggio’s "The Entombment of Christ." That wasn't an accident. By mimicking the way painters depicted the dead Jesus, David was subtly telling the public that Marat was a martyr for the people. He took a man who spent his days calling for executions and turned him into a symbol of quiet, selfless sacrifice.

The background is basically empty. It’s just a void of sickly green and brown. This forces your eyes down to the body. You see the wound—just a small, clean slit. In reality, it would have been a gory, traumatic mess. But David keeps it "classy." He omits the skin condition that forced Marat to live in that tub in the first place. Marat suffered from a debilitating disease, likely dermatitis herpetiformis, which caused agonizing itching and blisters. David paints him with smooth, heroic skin.

It’s a lie. But it’s a beautiful one.

The Letter and the Knife: Symbols of Betrayal

In Marat’s left hand, he holds a piece of paper. This is the letter Charlotte Corday used to gain access to his room. It reads: "Given that I am unhappy, I have a right to your help."

This is the core of the death of Marat meaning regarding his character. David is showing us that Marat was killed because of his kindness. He was "assassinated" while trying to help a citizen. On the crate next to the tub—which serves as a makeshift desk—there’s an assignat (revolutionary money) and a note instructions to give it to a war widow with five children.

Is it true? Maybe. Marat did give money to the poor. But David frames it so perfectly that you can’t help but see Marat as a victim of his own virtue.

💡 You might also like: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Then there’s the knife. It’s lying on the floor. It looks small, almost insignificant compared to the giant quill Marat still holds. The message? The pen is mightier than the sword, even in death. Marat’s words—his revolutionary ideas—will outlast the violence of his enemies.

Why the Bathtub Matters

Why was he in a tub anyway? Most people think it was just a weird 18th-century quirk. It wasn't.

As mentioned, Marat had a skin condition. The only way he could find relief was by soaking in a bath of diluted vinegar or medicinal herbs. He basically lived in that tub. He worked there. He ate there. He received visitors there. By placing the scene in the bathroom, David captures a moment of extreme vulnerability. It’s intimate. It feels wrong to look at, which is exactly why it’s so powerful. You’re seeing a man in his private sanctuary, murdered by a guest.

Corday: The Invisible Villain

The most interesting thing about the death of Marat meaning is who isn't in the frame. Charlotte Corday is gone.

By leaving her out, David robs her of her platform. She wanted to be a hero. She wanted to stand over the "monster" she had slain and claim her place in history. David denies her that. Instead, he focuses entirely on the aftermath. We only see the trace of her—the bloody knife and the deceptive letter.

Corday was actually a supporter of the Girondins, a more moderate revolutionary group. She believed Marat was a "hydra" whose radicalism was destroying France. She famously said, "I killed one man to save 100,000." She didn't hide. She waited for the police to come. She was executed four days later by guillotine.

The Secular Altar

Notice the wooden block. It looks like a tombstone. David even signed it "À MARAT, DAVID" (To Marat, from David).

This wasn't just a painting for a museum. It was designed to be carried through the streets in processions. It was meant to be an idol. At a time when the Revolution was trying to replace Christianity with the "Cult of Reason," they needed new "saints." Marat became the first.

The painting is surprisingly tall. When you stand in front of it at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, the tub is almost at eye level. It’s designed to make you feel like you are standing right there in the room with him. It’s an immersive propaganda experience.

📖 Related: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

Neoclassicism as a Weapon

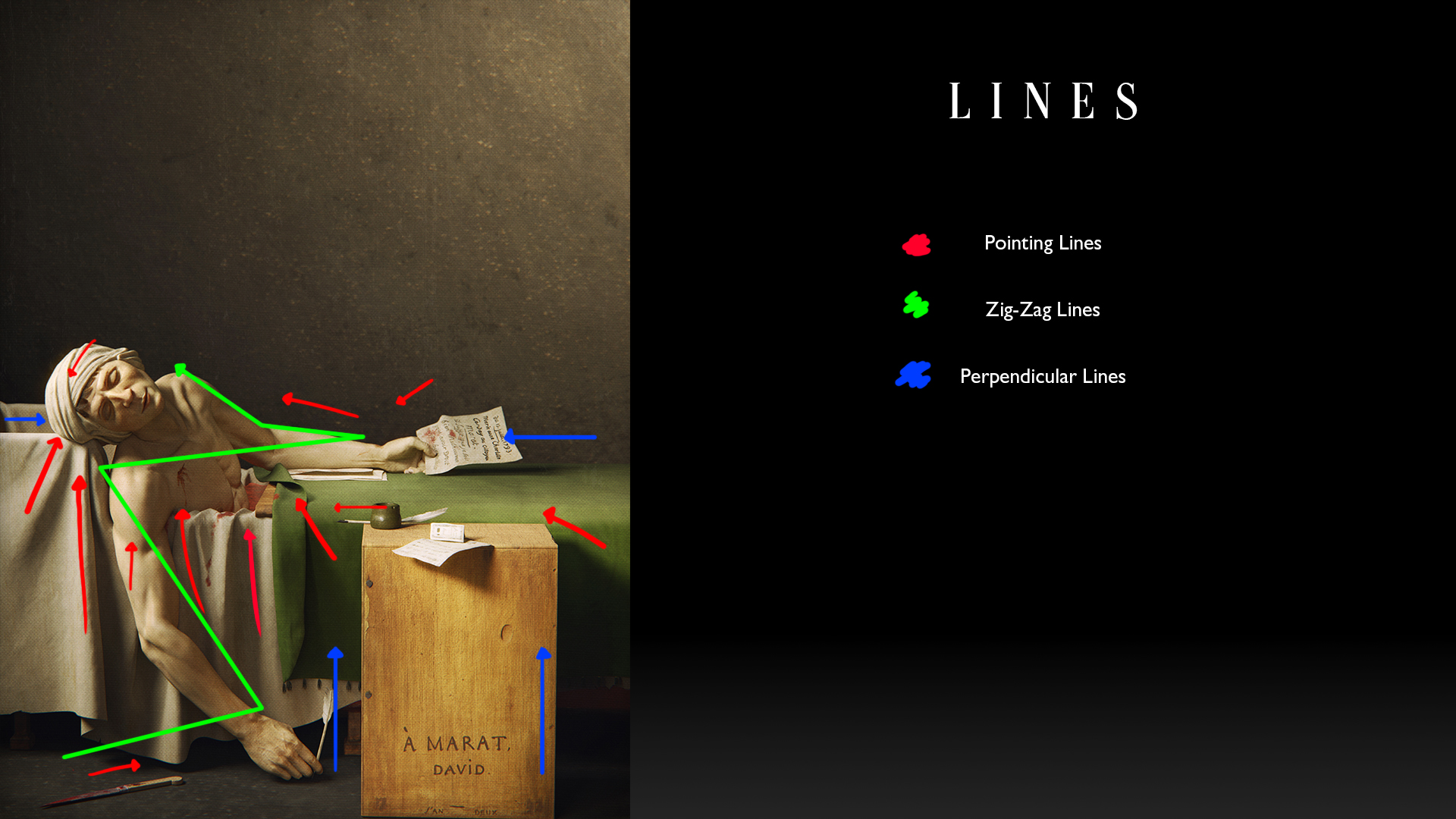

David used a style called Neoclassicism. It’s all about straight lines, clear light, and "noble simplicity." Before the Revolution, art was often Rococo—frilly, pink, and full of naked aristocrats playing in gardens.

David hated that.

He thought art should have a moral purpose. It should inspire citizens. So, he stripped away all the fluff. The death of Marat meaning is reinforced by this Spartan aesthetic. There are no fancy curtains or gilded mirrors. Just a man, a tub, and his work. It screams "Republican virtue."

What Most People Get Wrong

People often assume Marat was a saint because of this painting. He wasn't.

He was a man who advocated for the September Massacres, where over 1,000 prisoners were pulled from their cells and killed. He was a deeply divisive figure who used his newspaper, L'Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People), to incite violence against anyone he deemed an "enemy of the state."

If you look at contemporary accounts from people who weren't fans of the Revolution, they describe Marat as a filthy, angry, and obsessive man. David’s painting is a masterclass in "erasure." He erased the smell, the sores, and the rage, leaving only the "idea" of a hero.

Why We Still Care

Art historians love this painting because it marks the birth of modern political art. It’s the ancestor of the "Hope" poster or any wartime propaganda you’ve ever seen.

But it’s also just a hauntingly beautiful image.

The way the arm hangs—often called the "dead arm" motif—has been copied by everyone from Henry Wallis to movie directors. It’s a universal symbol of the end. There’s a stillness in the room that feels heavy.

👉 See also: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Even if you don't know anything about the French Revolution, you can feel the weight of that silence. That’s the true power of the death of Marat meaning. It transcends the specific politics of 1793 and taps into a raw, human feeling of loss and betrayal.

Critical Analysis: Acknowledging the Bias

We have to acknowledge that David was a political player. He wasn't an objective observer. He was a member of the Committee of General Security. He signed death warrants.

So, when we look at the death of Marat meaning, we are looking through the eyes of a true believer. This is art as a tool of the state. It’s brilliant, yes, but it’s also dangerous. It shows how easily art can be used to sanitize history and turn complex, flawed individuals into untouchable myths.

The Legacy of the Tub

After the fall of Robespierre and the end of the Terror, the painting became a liability. David himself was imprisoned for a while. The painting was returned to him in 1795 and stayed in his studio, hidden away, until his death in 1825.

It was too "hot" for the public to see. It reminded people of the bloodiest days of the Revolution. It wasn't until the mid-19th century that critics like Charles Baudelaire rediscovered it and praised it for its technical brilliance, regardless of its politics.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you want to truly appreciate the depth of this work, don't just look at the surface.

- Compare the versions. David’s studio made several copies. Look at the differences in the brushwork. The original in Brussels is widely considered the most emotionally raw.

- Look for the "Dead Arm." Once you see the way Marat’s arm hangs, you’ll see it everywhere in art history. It’s a direct reference to the "Pietà." Check out Michelangelo’s sculpture of the same name to see the inspiration.

- Research Charlotte Corday. To get the full death of Marat meaning, you need to understand the woman who held the knife. She wasn't a "madwoman"; she was a political actor with her own set of convictions.

- Visit the site (virtually). You can find 3D reconstructions of Marat’s apartment online. Seeing how small and cramped the space actually was makes David’s "epic" treatment of the scene even more impressive.

The death of Marat meaning isn't a static thing. It changes depending on who is looking at it. In 1793, it was a call to arms. In 1850, it was a masterpiece of realism. Today, it’s a warning about the power of the image to shape truth.

When you look at it, ask yourself: What is the artist trying to make me forget? Usually, that’s where the real story begins.