Look, most people hear "Russian literature" and immediately think of thousand-page doorstoppers that require a PhD and three pots of coffee to finish. But The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy is different. It’s short. It’s brutal. Honestly, it’s probably the most uncomfortable thing you’ll ever read because it isn’t really about 19th-century Russia—it’s about the soul-crushing realization that you might be living your life completely wrong.

Tolstoy wrote this after a massive spiritual mid-life crisis. He’d already finished War and Peace and Anna Karenina. He was famous, wealthy, and respected, yet he found himself staring into the abyss of his own mortality. He channeled all that existential dread into Ivan Ilyich, a guy who is basically the Victorian version of a corporate climber. Ivan isn’t a villain. He’s just... average. He wants a nice house, a respectable job, and people to think he’s important. Then he slips on a ladder while hanging curtains, gets a weird pain in his side, and everything falls apart.

What actually happens in The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy?

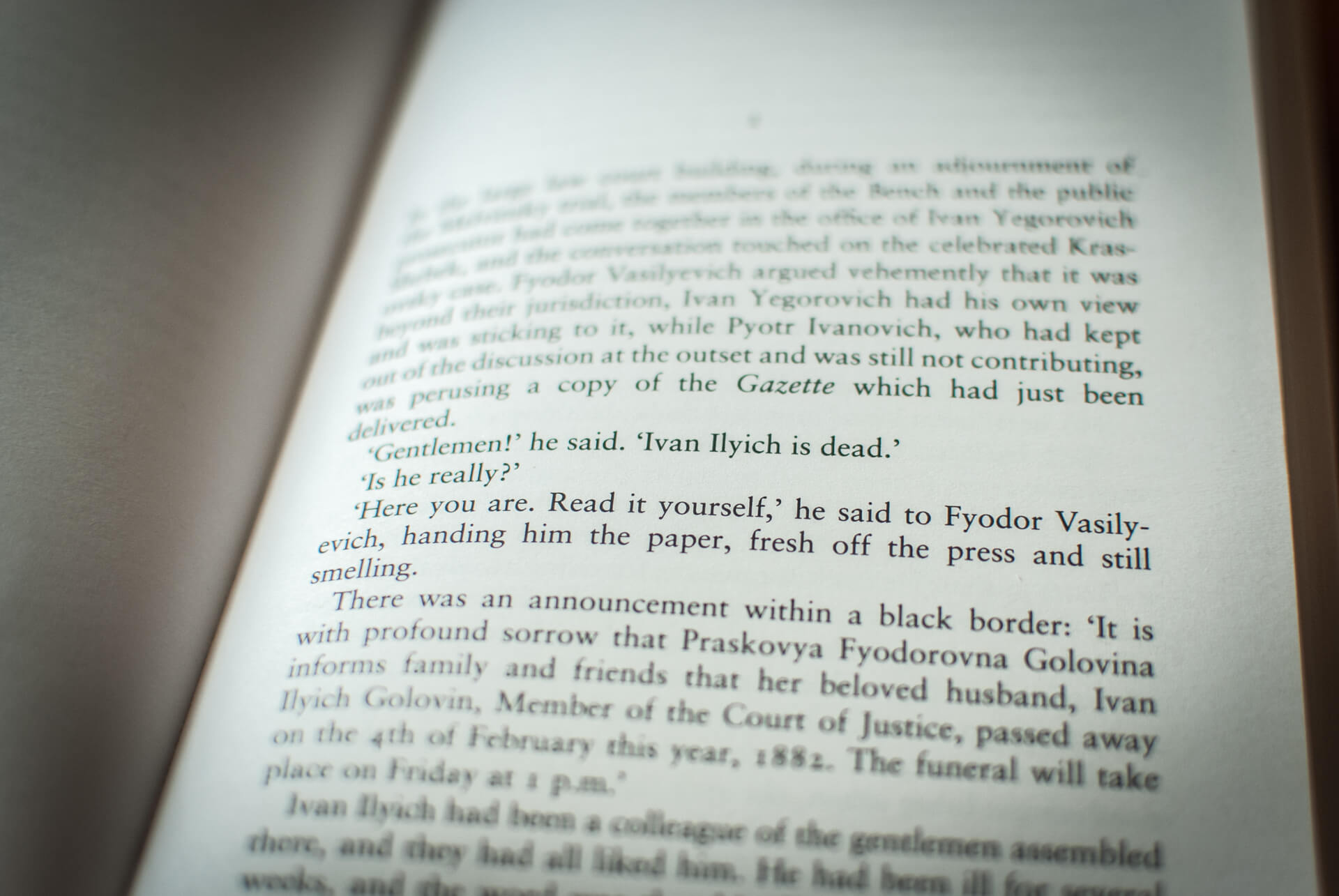

The story starts at the end. We see Ivan’s colleagues at his wake, and they aren't even sad. They’re literally thinking about who’s going to get his promotion and how they can get out of there in time to play bridge. It’s cold. It’s a gut punch. Tolstoy is showing us exactly how little the world cares about our professional titles once we’re gone.

Then we jump back in time. Ivan Ilyich Golovin is a judge. He’s lived a life that is le comme il faut—proper and correct. He marries a woman he doesn’t particularly like because it’s the "right" thing to do. He avoids conflict by burying himself in work. He’s obsessed with his social standing. When he gets sick after that domestic accident, he expects sympathy. Instead, he gets the same cold, "professional" treatment he used to give the defendants in his courtroom.

The physical decline is graphic. Tolstoy doesn't hold back on the smells, the screams, or the indignity of needing help with basic bodily functions. Ivan spends months in agony, realizing that his "perfect" life was actually a hollow shell. The only person who treats him with any real humanity is Gerasim, a young peasant servant. Gerasim doesn't lie to him. He doesn't pretend Ivan isn't dying. He just holds Ivan's legs up to ease the pain and shows genuine compassion because, in Gerasim's mind, everyone dies eventually, so why not be kind?

The "Ordinary" Life as a Nightmare

Tolstoy writes one of the most famous lines in literature here: "Ivan Ilyich's life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible."

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

That’s a weird thing to say, right? Why is an ordinary life terrible?

Because for Tolstoy, "ordinary" meant "unthinking." Ivan lived by the script society wrote for him. He never asked what he actually valued. He just chased the next paycheck and the next social invitation. He was a "pleasant, respectable, and decorous" man, but he was essentially a ghost before he even got sick.

The medical mystery and the "Side"

Ivan’s illness is never specifically named, though scholars and doctors have debated it for over a century. Some say it was kidney cancer; others point to peritonitis or bowel obstruction. In the 1880s, medicine was pretty primitive. But the diagnosis doesn't actually matter for the story. The illness is a plot device to strip away Ivan’s ego.

He visits famous doctors. They act exactly like he did as a judge—treating him as a "case" rather than a person. They argue about "floating kidneys" and "appendix" issues while Ivan is sitting there terrified of the void. This irony is thick. He spent his life being the "expert" who didn't care about the humans behind the legal papers, and now he’s on the receiving end of that same bureaucratic coldness.

Why this story feels so modern

If you swap the 1880s carriage for a Tesla and the bridge games for mindless scrolling on social media, nothing has changed. We still measure our worth by the curtains we hang and the titles on our LinkedIn profiles.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Vladimir Nabokov, the guy who wrote Lolita, was famously picky about other writers. He usually hated "message-driven" fiction. But he called The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy one of the greatest works of Russian literature ever. Why? Because the artistry is so tight. There’s no wasted space. Every detail, from the way Ivan fumbles with his silk buttons to the "black hole" he sees at the end, is designed to make the reader feel the weight of a wasted life.

It's also a story about the "lie." Ivan is surrounded by people—his wife Praskovya, his daughter—who refuse to acknowledge he is dying. They treat his illness as a "nasty habit" or an inconvenience. This gaslighting makes his physical pain ten times worse. Only Gerasim is honest. There's a huge lesson there about how we treat the sick and the elderly in our own "polite" society. We isolate them because they remind us of our own eventual end.

The moment of light

The ending is... wild. Ivan spends three days screaming. Literally just screaming. He’s fighting the "black sack" he’s being pushed into. He’s terrified. But then, in his final moments, his young son catches his hand and kisses it.

Ivan feels sorry for the kid. He looks at his wife and feels sorry for her too. In that moment of stepping outside his own ego and feeling actual empathy for others, the fear vanishes. The "black hole" turns into light. He realizes that while his life was "not the right thing," he can still make it right in the final seconds by letting go of his selfishness.

He tries to say "Forgive me," but he’s so weak it comes out as "Forego." And it doesn't matter. He’s at peace.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Actionable insights from Ivan’s mistakes

You don't have to wait for a terminal illness to figure this stuff out. Tolstoy isn't just trying to depress you; he's trying to wake you up. If you want to avoid the "terrible" ordinary life Ivan led, here are some things to think about:

- Audit your "Shoulds": Look at your weekly schedule. How many of those things are you doing because you actually care, and how many are because you think you "should" to maintain a certain image? Ivan’s life was 100% "should."

- Practice radical honesty: The most painful part of Ivan's death was the lying. Surround yourself with people who can tell you the truth, and be that person for others.

- Empathy is the antidote to ego: Ivan’s pain only subsided when he stopped thinking about his own suffering and started thinking about the suffering his death was causing his family.

- Physicality matters: Don't ignore your body. Ivan's obsession with his decor and his "decorous" behavior led him to ignore his physical reality until it was too late.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy is a heavy read, but it’s a short one. You can finish it in an afternoon. It might ruin your day, but it might also change how you spend the next ten years. It forces you to ask: if I were Ivan on that sofa today, would I be screaming about my curtains, or would I be okay with the life I’ve built?

If you're feeling stuck in a corporate rut or just going through the motions, read this. It's a reminder that the "decorous" life is often the most dangerous one. Tolstoy knew it, Ivan found it out the hard way, and we're still trying to learn it today.

Go find a copy. Read the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation if you can—it captures the grit and the weirdness of Tolstoy’s late style much better than the older, flowery versions. Put your phone in another room. Let the existential dread wash over you. It's good for you.

Next Steps for Deep Reading:

- Read the Gerasim scenes twice. Notice how Tolstoy uses physical touch to contrast with the cold, verbal-only interactions of the upper class.

- Look for the "curtain" metaphor. Pay attention to how the very thing that "killed" him (decorating) becomes a symbol for his entire shallow existence.

- Compare Ivan to his colleagues. The first chapter is essential for understanding the world Ivan left behind—one that replaces human connection with "professionalism."