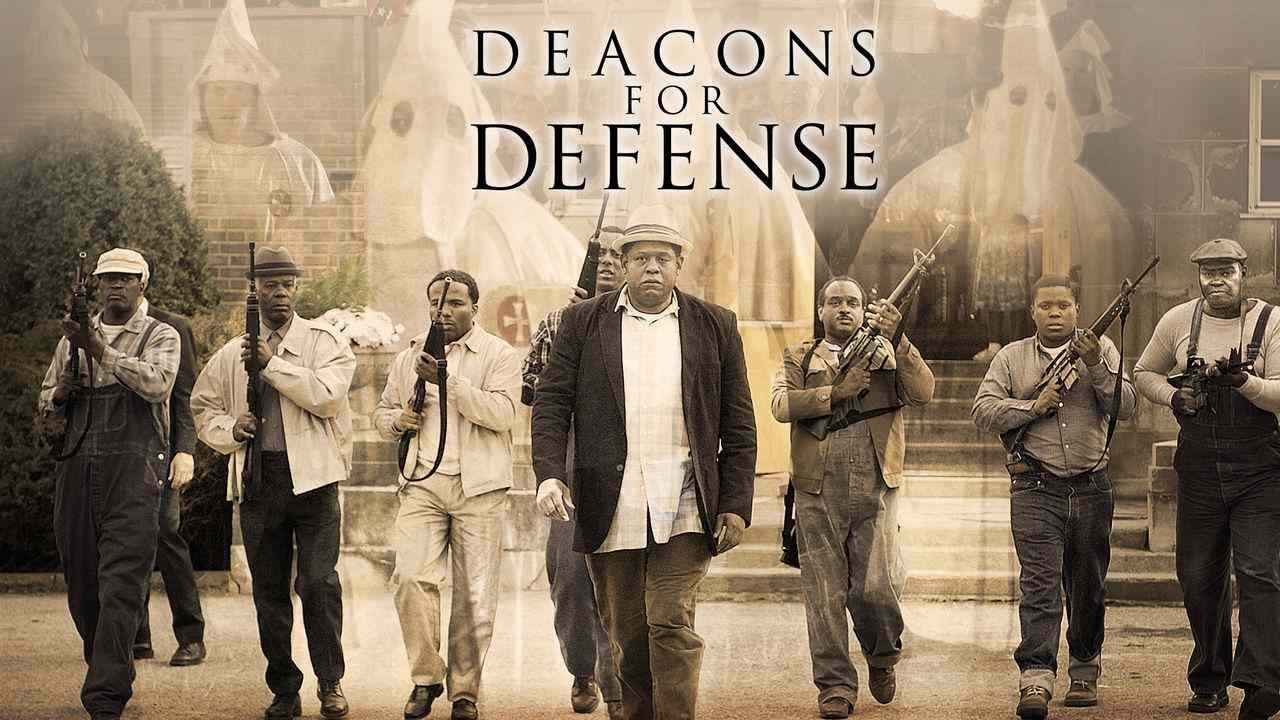

You’ve probably seen the grainy footage of peaceful protesters being hosed down in Birmingham or Selma. It’s the standard history book narrative. But there is another side to the story, one that involves shotguns, night watches, and a group of Black men who decided they were done being victims. That’s the core of the Deacons of Defense movie, a 2003 Peabody Award-winning film that honestly doesn't get enough credit for how it reframes the Civil Rights Movement.

Most people think non-violence was the only strategy used in the 60s. It wasn't.

Forest Whitaker plays Marcus Clay, a character based on the real-life men of Bogalusa, Louisiana. The film is a dramatization, sure, but it’s rooted in the very real history of the Deacons for Defense and Justice. These weren't "revolutionaries" in the way we often think of the Black Panthers later on. They were fathers. They were WWII veterans. They were blue-collar workers at the local crown-zellerbach paper mill who realized that if they didn't protect their houses, nobody would.

The Reality Behind the Deacons of Defense Movie

The movie takes us back to 1964. Bogalusa is a powder keg. The Ku Klux Klan isn't just a fringe group here; they are the police force, the local government, and the neighbors next door. When the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) shows up to register voters, the violence spikes.

In the film, Whitaker’s character is hesitant at first. He believes in the system, or at least he wants to. But there is a specific turning point—a moment of raw, ugly realization—when he sees that the local authorities aren't just failing to protect his community, they are actively participating in the terror.

Real life was just as brutal. The actual Deacons were founded by guys like James Knight and Robert Hicks. Imagine being a black man in the deep south, seeing a cross burning on your lawn, and instead of calling the cops—who likely lit the fire—you grab a M1 carbine and sit on your porch. That is the tension the Deacons of Defense movie captures so well. It’s not about looking for a fight. It’s about ending one.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Why Forest Whitaker Was the Perfect Choice

Whitaker has this way of looking haunted and powerful at the same time. In this role, he has to balance the philosophy of Dr. King with the practical reality of living in a town where the Klan owns the night. His performance anchors the movie, making it feel less like a "history lesson" and more like a noir thriller.

The supporting cast is solid too. Ossie Davis shows up, bringing that gravitas he always had. Jonathan Silverman plays a CORE activist, representing the white reformers who came down South. The friction between the idealistic, non-violent activists and the pragmatic, armed Deacons provides the best dialogue in the script. It asks the question: Can you truly have a non-violent movement if there isn't a "force" behind it to ensure the protesters aren't slaughtered in their sleep?

Fact vs. Fiction: What the Movie Gets Right

It’s easy to dismiss TV movies as "history-lite," but this one stays surprisingly close to the spirit of the Bogalusa chapter.

- The Police Complicity: The film correctly depicts the local police as an extension of the Klan. This wasn't an exaggeration. In the mid-60s, the line between the badge and the robe was invisible in many Louisiana parishes.

- The Military Discipline: These guys weren't a mob. They were organized. They had radios. They had patrols. The movie shows this tactical side, which is historically accurate. Many founders were veterans who used their military training to set up a perimeter around the Black community.

- The Tension with CORE: This is a huge point. Civil Rights leadership was often terrified that armed self-defense would ruin their public image and give the federal government an excuse to crack down on them. The film explores this "internal" conflict beautifully.

However, some characters are composites. Marcus Clay isn't a single real person but a blend of several leaders like Robert Hicks and A.Z. Young. While the film narrows the scope to a few key incidents, the real Deacons had chapters across Louisiana and eventually into Mississippi and Alabama. They were a massive logistical operation that the movie can only hint at due to its runtime.

Why Nobody Talks About This Film Anymore

Honestly? It makes people uncomfortable.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

We like our Civil Rights stories to be about turning the other cheek. It's a cleaner narrative for school assemblies. The Deacons of Defense movie challenges that by suggesting that the "success" of non-violence often depended on the "threat" of self-defense. It’s a nuanced take on the Second Amendment that doesn’t fit into modern political boxes.

The movie aired on Showtime, which at the time meant it didn't get the massive theatrical push of something like Selma or Malcolm X. But its influence persists. You can see its DNA in more recent projects like Watchmen or Lovecraft Country, which dive into the "hidden" history of Black resistance in the South.

The Cinematography of the Deep South

The film looks humid. You can almost feel the sweat and the mosquitoes. The director, Bill Duke—who you might know as the massive guy from Predator or the director of A Rage in Harlem—knows how to shoot tension. He uses shadows effectively, reminding us that for the people living this, the night was a character itself. A dangerous one.

There’s a specific scene where the Deacons drive their cars into a standoff to protect a group of marchers. The way the headlights cut through the dark, facing down the police and the Klan simultaneously, is one of the most badass moments in 2000s cinema. It’s a "stand your ground" moment that actually means something.

Practical Takeaways for Film Buffs and History Lovers

If you're going to watch the Deacons of Defense movie, don't just treat it as background noise.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

First, look for the subtle ways the film discusses class. The Deacons were working-class men. This wasn't an academic movement; it was a labor movement and a survival movement. The mill where they worked is central to the plot because it was their only leverage.

Second, pay attention to the women. While the movie focuses on the men with guns, the real-life movement relied heavily on the women who ran the communications and kept the community together while the men were on patrol. The film gives glimpses of this, but the real history is even deeper.

Finally, compare it to the book The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement by Lance Hill. If the movie sparks your interest, Hill’s book is the definitive deep-dive. It goes into the FBI files and the internal memos that show just how much the federal government was freaked out by these guys.

Next Steps for Your Viewing and Research:

- Watch the film: It’s often available on streaming platforms like Paramount+ or for digital rental. It’s worth the two hours just for Whitaker's performance.

- Research the Bogalusa Movement: Look up the "1965 Bogalusa protests." The real footage of those marches, where the Deacons walked the perimeter, is more intense than anything Hollywood could film.

- Explore Bill Duke’s filmography: He has a knack for telling stories about the Black experience that avoid the usual clichés. Check out Hoodlum if you want more historical drama with a bite.

- Read the CORE perspective: To understand why there was so much friction, look up James Farmer’s writings. He was the head of CORE and had a very complicated relationship with the idea of armed guards.

The Deacons of Defense movie isn't just a period piece. It's a look at what happens when the social contract breaks down entirely. It's about the moment people decide that their lives are worth defending, even if the world tells them otherwise.